Treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS) is defined as nonresponse to at least 2 trials of antipsychotic medication of sufficient dose and duration and affects about 30% of people who are diagnosed with schizophrenia.1 We describe a case of TRS in a person with Turner syndrome.

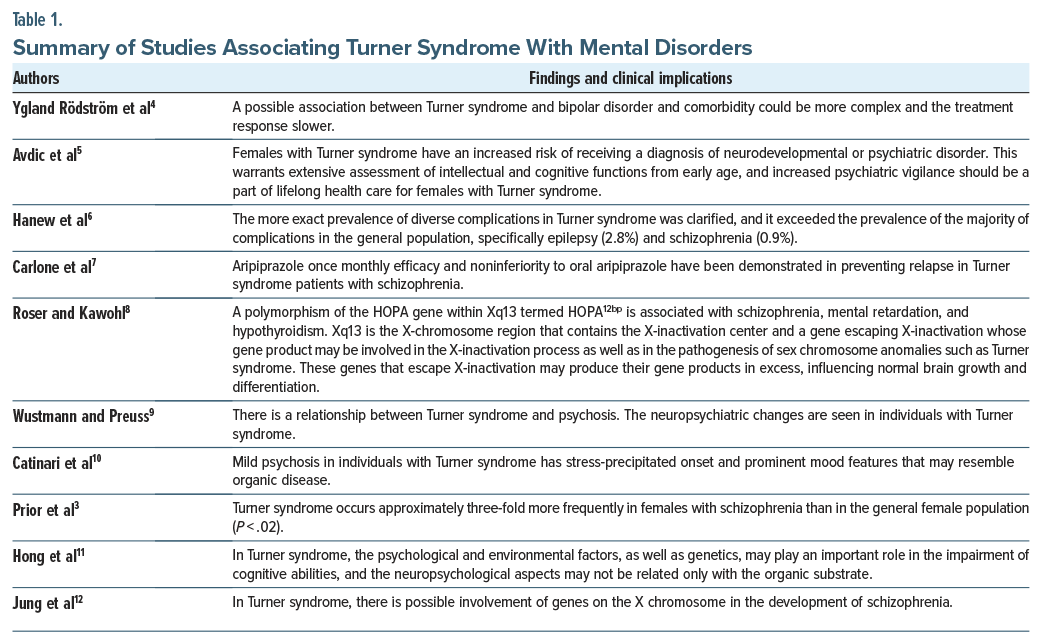

Turner syndrome, a sex chromosomal disorder that cannot occur in males, is found in nearly 1 of 2,500 live female births.2 Turner syndrome is characterized by 45X monosomy, 45X/46XX mosaicism, or X chromosome structural abnormality in 60%, 30%, and 10% of cases, respectively. Turner syndrome primarily affects the reproductive, skeletal, and lymphatic systems. Neuropsychiatric problems including schizophrenia, attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder, autism, and cognitive difficulties have been reported.3 Table 1 provides an overview of findings in the medical literature relevant to the case as described below.

Case Report

Ms A is a 47-year-old woman who was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit of a suburban academic medical center located in the northeast United States. Her symptoms included command auditory hallucinations, disorganized behavior, agitation, and paranoid delusions. Pertinent past psychiatric history included a diagnosis of schizophrenia with 4 previous psychiatric hospitalizations for similar episodes of psychosis. Notable family history includes a maternal history of schizophrenia. In addition, the significant medical history of the patient includes hypothyroidism, type II diabetes mellitus, asthma, dyslipidemia, and irritable bowel syndrome.

Her course in the hospital was notable for progressive disorganized behavior, selective mutism, and paranoid delusions, despite the use of multiple antipsychotics including fluphenazine and quetiapine. In the past, she had also received clozapine, loxapine, lurasidone, and haloperidol. During Ms A’s most recent hospitalization, she began to develop periods of confusion, during which she became disoriented to her surroundings and exhibited altered mental status. This led to bizarre behaviors for the patient including increased agitation and spreading of her feces, which was not exhibited with previous episodes of psychosis or hospitalizations. In one instance, she became agitated and threw herself to the floor, resulting in a displaced fracture of the right humerus requiring surgical intervention.

During this hospitalization, a head computed tomography scan was done as well as head magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast, which were both negative for any acute changes. Upon further workup with karyotyping, it was determined that the patient carried 45X/46XX mosaicism for Turner syndrome. The patient’s hospital course was further complicated by the treatment of cholelithiasis and urinary tract infection. Another clozapine trial was initiated following this finding; however, it was abruptly stopped due to tachycardia. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was also considered but was opposed by the patient’s family. Ultimately, the patient was stabilized on a combination of risperidone, quetiapine, valproic acid, and duloxetine. As Ms A became lucid and more oriented to self, place, and situation, she appeared less internally preoccupied and distressed by the symptoms of psychosis. The patient no longer endorsed command auditory hallucinations, and there was a significant reduction in the frequency and intensity of paranoid delusions.

Discussion

This patient was found to have TRS based on nonresponse to numerous trials of antipsychotic medications. After the Turner syndrome mosaicism was established, this informed further treatment course by considering ECT and reinitiating clozapine. Ultimately, a combination of second-generation antipsychotics, a mood stabilizer, and a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor led to remission of the acute psychotic episode for the patient. Given the complexity of the treatment course, it is likely that the genetic component of Turner syndrome mosaicism contributed to her psychosis, and this may have contributed to her suboptimal response to several psychopharmacologic interventions.

The empirical literature has hypothesized that a locus within the X chromosome defined as the pseudo-autosomal region is associated with schizophrenia due to changes in normal brain development.7 This has led to the examination of other components of the X chromosome outside of this locus, including Xp21 associated with the development of schizophrenia.13 In addition, the Xp13 region, where the HOPA gene is located which plays a role in fetal development, may also be involved in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.14

The association of mental health conditions with Turner syndrome has been reported. Although the level of evidence remains weak, the clinical complexity in persons with Turner syndrome and cooccurring affective illness, cognitive impairments, neurodevelopmental disorders, and schizophrenia brings unique challenges.15 In clinical settings, Turner syndrome with schizophrenia inspires inquiries into how genetics and antipsychotic medications may be utilized given these individuals have partial or no response to treatment.16 There are a few reports of ECT for treatment-refractory catatonia symptoms in Turner syndrome patients, although there is a lack of evidence about specific therapeutics.17 This case report adds to the literature on Turner syndrome and psychosis and is an example of the heterogeneity of individuals who meet the criteria for TRS.

Article Information

Published Online: October 7, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr03980

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr03980

Submitted: February 2, 2025; accepted June 23, 2025.

To Cite: Gupta M, D’Souza VC, Citrome L. Mosaic Turner syndrome and treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr03980.

Author Affiliations: Southwood Children’s Behavioral Healthcare, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (Gupta); Alberta Health Services, Medicine Hat, Alberta, Canada (D’Souza); New York Medical College, Valhalla, New York (Citrome).

Corresponding Author: Mayank Gupta, MD, Southwood Children’s Behavioral Healthcare, 2575 Boyce Plaza Rd, Pittsburgh, PA 15241 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Citrome serves as a consultant to AbbVie/Allergan, Acadia, Adamas, Alkermes, Angelini, Astellas, Avanir, Axsome, Biogen, BioXcel, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cadent Therapeutics, Cerevel, Clinilabs, COMPASS, Delpor, Eisai, Enteris BioPharma, HLS Therapeutics, Idorsia, INmune Bio, Impel, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Karuna, Lundbeck, Luye, Lyndra, MapLight, Marvin, Medavante-ProPhase, Merck, Mitsubishi-Tanabe Pharma, Neumora, Neurocrine, Neurelis, Noema, Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Ovid, Praxis, Recordati, Relmada, Reviva, Sage, Sumitomo/Sunovion, Supernus, Teva, University of Arizona, Vanda, and Wells Fargo; does one-off ad hoc consulting for individuals/entities conducting marketing, commercial, or scientific scoping research; is a speaker for AbbVie/Allergan, Acadia, Alkermes, Angelini, Axsome, BioXcel, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Idorsia, Intra-Cellular Therapies, Janssen, Lundbeck, Neurocrine, Noven, Otsuka, Recordati, Sage, Sunovion, Takeda, Teva, Vanda, and CME activities organized by medical education companies such as Medscape, NACCME, NEI, Vindico, and Universities and Professional Organizations/ Societies; owns stocks (small number of shares of common stock) in Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, J & J, Merck, and Pfizer purchased >10 years ago; has stock options in Reviva; and earns royalties/publishing income from Taylor & Francis (Editor-in-Chief, Current Medical Research and Opinion, 2022-date), Wiley (Editor-in-Chief, International Journal of Clinical Practice, through end 2019), UpToDate (reviewer), Springer Healthcare (book), Elsevier (Topic Editor, Psychiatry, Clinical Therapeutics). Drs Gupta and D’Souza report no relevant financial relationships.

Funding/Support: None.

Additional Information: Information has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

References (17)

- Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, et al. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: treatment response and resistance in psychosis (TRRIP) working group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(3):216–229. PubMed CrossRef

- Ranke MB, Saenger P. Turner’s syndrome. Lancet Lond Engl. 2001;358(9278):309–314. PubMed CrossRef

- Prior TI, Chue PS, Tibbo P. Investigation of Turner syndrome in schizophrenia. Am J Med Genet. 2000;96(3):373–378. PubMed CrossRef

- Ygland Rödström M, Johansson BA, Bäckström B, et al. Acute mania and catatonia in a teenager successfully treated with electroconvulsive therapy and diagnosed with Turner syndrome and bipolar disorder. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2021;2021:3371591. PubMed

- Avdic HB, Butwicka A, Nordenström A, et al. Neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders in females with Turner syndrome: a Population-based Stud. J Neurodev Disord. 2021:13:51. PubMed

- Hanew K, Tanaka T, Horikawa R, et al. Prevalence of diverse complications and its association with karyotypes in Japanese adult women with Turner syndrome-a questionnaire survey by the Foundation for Growth Science. Endocr J. 2018;65(5):509–519. PubMed CrossRef

- Carlone C, Pompili E, Silvestrini C, et al. Aripiprazole once-monthly as treatment for psychosis in Turner syndrome: literature review and case report. Riv Psichiatr. 2016;51(4):129–134. PubMed CrossRef

- Roser P, Kawohl W. Turner syndrome and schizophrenia: a further hint for the role of the X-chromosome in the pathogenesis of schizophrenic disorders. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(2 Pt 2):239–242. PubMed CrossRef

- Wustmann T, Preuss UW. Turner-syndrome and psychosis: a case report and brief review of the literature. Psychiatr Prax. 2009;36(5):243–245. PubMed CrossRef

- Catinari S, Vass A, Heresco-Levy U. Psychiatric manifestations in Turner syndrome: a brief survey. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2006;43(4):293–295. PubMed

- Hong D, Scaletta Kent J, Kesler S. Cognitive profile of Turner syndrome. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2009;15(4):270–278. PubMed CrossRef

- Jung SY, Park JW, Kim DH, et al. Mosaic Turner syndrome associated with schizophrenia. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;19(1):42–44. PubMed CrossRef

- Zatz M, Vallada H, Melo MS, et al. Cosegregation of schizophrenia with Becker muscular dystrophy: susceptibility locus for schizophrenia at Xp21 or an effect of the dystrophin gene in the brain?. J Med Genet. 1993;30(2):131–134. PubMed CrossRef

- Brown CJ, Ballabio A, Rupert JL, et al. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature. 1991;349(6304):38–44. PubMed CrossRef

- Good CD, Lawrence K, Thomas NS, et al. Dosage-sensitive X-linked locus influences the development of amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex, and fear recognition in humans. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 11):2431–2446. PubMed CrossRef

- Kawanishi C, Kono M, Onishi H, et al. A case of Turner syndrome with schizophrenia: genetic relationship between Turner syndrome and psychosis. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;51(2):83–85. PubMed CrossRef

- Xia Y, Sun Y, Zhi Q, et al. A case report of a patient with Turner syndrome who develops catatonia secondary to psychotic symptoms. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(14):e37730. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!