To the Editor: Law enforcement transport for individuals in behavioral health crises, often involving handcuffs and restraints, results in significant financial costs and psychological trauma, reinforcing criminalization and stigma while worsening mental health conditions.1,2 Involuntary commitment laws, while protective, can discourage help seeking due to legal and economic consequences such as limitations on firearm access and employment opportunities.3 Although beneficial, crisis intervention team programs face limitations due to reliance on law enforcement.4 These issues emphasize the need for community-based models like North Carolina’s Behavioral Evaluation and Response (BEAR) Team, which provides compassionate crisis support at no cost to the patients.5

This report, based on publicly available information and insights from the director of the BEAR team, examines how alternative approaches can mitigate trauma and foster recovery. Currently, the BEAR team is funded through opiate settlement funds, US Department of Justice grants, and the American Rescue Plan Act. Services are provided at no cost to patients, as medical insurance or Medicaid does not cover these intervention services, and per their assessment, it is often more costly to bill insurance than to receive reimbursements. Looking ahead, the team plans to continue relying on grants, as several funding opportunities are available, and the city has agreed to support this initiative should grant funding become unavailable.

Since the program’s inception, few adjustments have been made to adequately address community needs. The original grant funded 6 crisis counselors, which proved insufficient for 24/7 service. To ensure adequate coverage, the team added 4 more counselors starting in 2025. While the initial structure did not account for round-the-clock service, extending availability is crucial for providing a true alternative to law enforcement.

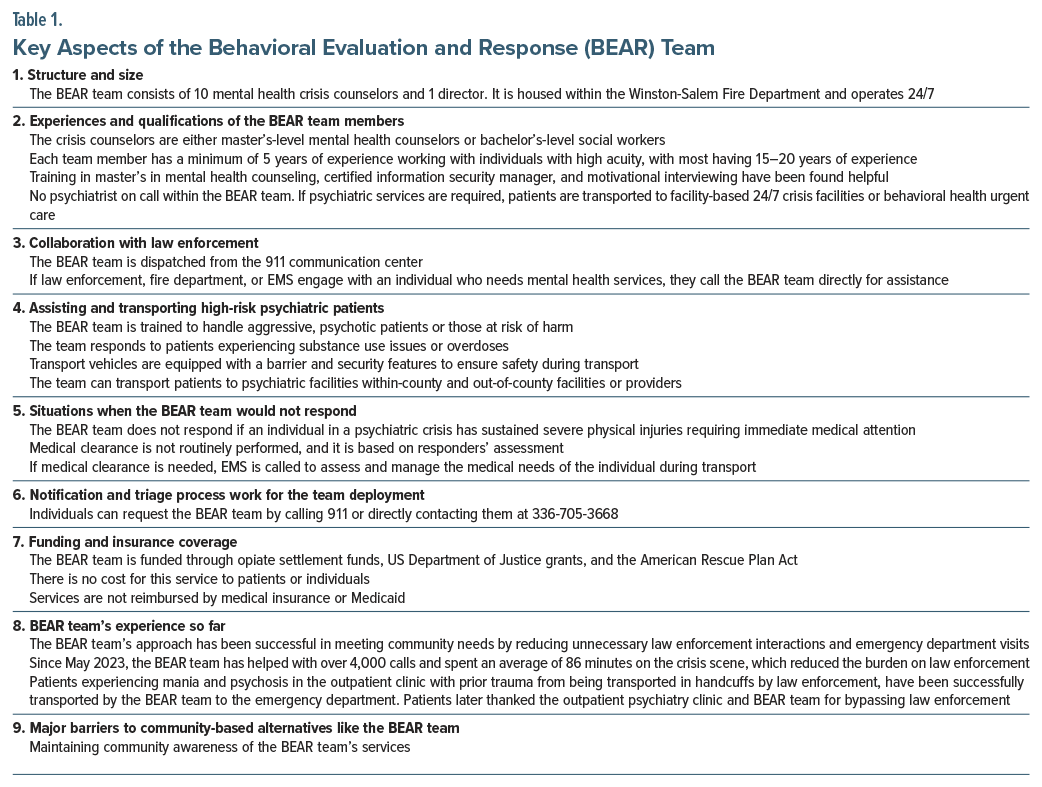

Since May 2023, the BEAR team has responded to over 4,000 calls, spending an average of 86 minutes on each crisis scene, effectively alleviating the burden on law enforcement. The team has observed that their services are beneficial to a wide array of patients, except those who voluntarily decline help. Staff members equipped with advanced training in mental health counseling, certified information security management, and motivational interviewing have proven to be highly effective. Furthermore, the team’s cross-training has been particularly valuable in high-acuity situations, where they often serve as the sole initial resource. We have summarized key aspects of the BEAR team’s functioning in Table 1 to encourage similar approaches for scalability in community-based crisis response.

Emulating the BEAR team’s success could reshape crisis intervention across the nation. Potential barriers to implementing community-based crisis responses include insufficient funding, limited mental health resources, public misconceptions about mental health and crisis intervention, and acuity and aggressiveness of patients.

Establishing effective community-based programs requires long-term financial commitment, public education, and policy reform to destigmatize mental health crisis response as part of essential public health services.

In summary, the financial and psychological costs of law enforcement–based responses to behavioral crises highlight the urgent need for community-based alternatives. North Carolina’s $10 million funding represents a significant step toward humane crisis intervention.1 This funding supports the development of specialized mental health crisis teams that decrease law enforcement involvement, fostering a more compassionate response. Programs like the BEAR team provide a promising framework, yet wider implementation of community-based models is essential to address behavioral health crises sustainably. With proper investment and policy reform, community-based crisis response systems can improve recovery outcomes, restore trust in mental health services, and reinforce public health infrastructure.

Article Information

Published Online: June 12, 2025.

https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.24lr03896

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(3):24lr03896

To Cite: Shah K, Munjal S. Need for community-based alternatives to law enforcement in behavioral crisis transport. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(3):24lr03896.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (Shah, Munjal).

Corresponding Author: Kaushal Shah, MD, MPH, MBA, Department of Psychiatry, Wake Forest University, 791 Jonestown Rd, Winston-Salem, NC 27103 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

References (5)

- North Carolina Newsline. North Carolina Should Embrace an Important Change in How It Aids People in Behavioral Health Crises. 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://ncnewsline.com/2024/03/21/north-carolina-should-embrace-animportant-change-in-how-it-aids-people-inbehavioral-health-crises/

- Psychiatric Times. Navigating the Intersection of Mental Health, Racism, and Law Enforcement. 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/navigating-the-intersection-of-mental-health-racism-and-law-enforcement

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Possession of Firearms by People With Mental Illness. 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.ncsl.org/civil-and-criminal-justice/possession-of-firearms-by-people-with-mental-illness

- NAMI. Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) programs. National Alliance on Mental Illness; 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.nami.org/advocacy/crisis-intervention/crisis-intervention-team-cit-programs/

- City of Winston-Salem. Behavioral Evaluation and Response (BEAR) Team. 2024. Accessed November 14, 2024. https://www.cityofws.org/3400/Behavioral-Evaluation-Response-Team

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!