Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) is characterized by muscle rigidity, altered mental status, autonomic dysfunction, and hyperthermia, typically following initiation or dose escalation of antipsychotics.1,2 While haloperidol is the most commonly implicated agent, atypical antipsychotics such as clozapine, risperidone, and olanzapine can also precipitate NMS—often with milder or atypical presentations.1,3,4 The pathophysiology is believed to involve dopaminergic blockade, primarily within the hypothalamus and basal ganglia, with additional roles for serotonergic and GABAergic systems.2,5 Although electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is considered a potential therapeutic option in NMS management,2,6 it has paradoxically been associated with NMS onset in rare instances.1,4 The lack of standardized diagnostic tools complicates recognition, especially in cases involving polypharmacy or second-generation antipsychotics.1,4,7 Risk factors include male sex, dehydration, younger age, and prior NMS episodes.3,4 In this context, the clinician’s role in detecting subtle, evolving symptoms becomes critical.

Case Report

A 51-year-old man with chronic schizophrenia was admitted to the hospital following a suicide attempt and increased aggression. He had previously responded partially to clozapine (400 mg/day) and intermittent ECT. During this admission, due to persistent psychotic symptoms and suicidal ideation, ECT was reinitiated while continuing clozapine.

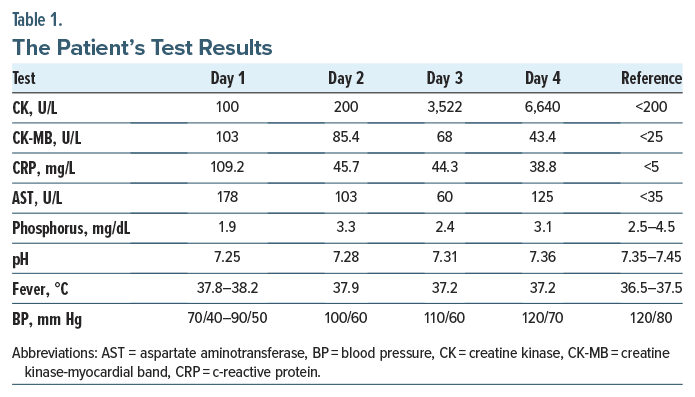

After 3 ECT sessions, the patient was found unresponsive, with hypotension (70/40 mm Hg), tachycardia (112 bpm), cyanosis, and confusion. His temperature ranged between 37.8°C (100.04°F) and 38.2°C (100.76°F). Arterial blood gas analysis showed a pH of 7.28 and oxygen saturation of 85%. Initial laboratory values and imaging ruled out infections or structural pathology. While early signs of muscle rigidity were absent, elevated creatine kinase levels were noted. Rigidity developed on the third day post-ECT discontinuation.

Neurology consultation confirmed NMS, and the patient was transferred to intensive care. Clozapine and ECT were discontinued. After stabilization, he was successfully maintained on aripiprazole and lithium, with no rehospitalizations for 2 years (Table 1).

Discussion

This case underscores the diagnostic challenges of NMS when it presents atypically, as frequently seen with clozapine-induced cases. In such instances, classical symptoms like persistent hyperthermia and early rigidity may be absent or delayed.4,7 Our patient exhibited only mild fever (37.8–38.2°C [100.04–100.76°F]) and developed rigidity 3 days after discontinuation of ECT—an observation aligned with reports that ECT may obscure or postpone neuromuscular symptoms.4,6

Clozapine, while effective for treatment-resistant schizophrenia and suicidality, carries a variable but real risk for NMS.1,3,8,9 Notably, it has been associated with atypical NMS presentations involving more pronounced autonomic instability and altered mental status rather than hyperthermia and rigidity.3,4 Furthermore, the patient’s stabilization on aripiprazole and lithium post-NMS, without recurrence for 2 years, aligns with findings that clozapine reinitiation is not always necessary and alternative agents may be safe and effective.6,9

The interplay between ECT and antipsychotics in the pathogenesis of NMS remains unclear. Although ECT is occasionally used to treat severe or refractory NMS,2 it has also been reported to trigger NMS in susceptible individuals.1,4 This duality requires careful clinical decision-making when considering its use in patients already at risk.

Ultimately, the absence of consensus diagnostic criteria for NMS1,2,7 necessitates high clinical suspicion, especially in complex treatment regimens. Our case contributes to a growing body of evidence suggesting that second-generation antipsychotics and ECT, though widely used, may harbor synergistic risk for NMS under certain conditions.

Article Information

Published Online: October 16, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04002

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25cr04002

Submitted: May 16, 2025; accepted July 3, 2025.

To Cite: Karatas KS. Development of neuroleptic malignant syndrome after administration of clozapine and electroconvulsive therapy in a patient with schizophrenia.Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5): 25cr04002.

Author Affiliation: Department of Psychiatry, Kutahya Health Sciences University, Kutahya, Turkey.

Corresponding Author: Kader Semra Karatas, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Kutahya Health Sciences University, Kutahya, Turkey ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Written informed consent was received from the patient to publish the case report, and information has been de-identified to protect anonymity.

ORCID: Kader Semra Karatas: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3595-8019

References (9)

- Gurrera RJ, Caroff SN, Cohen A, et al. An internationalconsensus study of neuroleptic malignant syndrome diagnostic criteria using the Delphi method. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(9):1222–1228. PubMed CrossRef

- Kumar S, Patel MA. Neuroleptic-induced hyperthermia: mechanisms and clinical management. BMC Neurol. 2023;23:77. PubMed

- Davis AL, Thompson BJ. Pharmacogenetics and neuroleptic malignant syndrome susceptibility. CNS Drugs. 2024;38(1):15–25. PubMed

- Lin Y, Hernandez KA. Catatonia or NMS? Differential diagnosis in psychiatric emergencies. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2023;46(2):273–288.

- Nguyen HT, Garcia F. Re-examining dopamine blockade in NMS: insights from recent case reviews. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1223345.

- Singh RP, Choi ES. Aripiprazole and NMS: a rare but serious concern. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2023;13:20451253231123456.

- Zhou M, Park JH. Risk factors for neuroleptic malignant syndrome in polypharmacy settings. Lancet Psychiatry. 2024;11(1):44–52.

- Al-Shammari F, Rivera MJ. Long-acting injectables in psychiatry: safety considerations and rare adverse events. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;26(3):211–219.

- Okafor A, Wallace G. Pathophysiology of NMS: new perspectives. J Neurol. 2024;271(4):1087–1094.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!