Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04033

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you been struck by how disruptive and dangerous rage can be to interpersonal relationships, work, academic activities, and happiness? Have you wondered why rage reactions occur and how they can be evaluated? Have you been uncertain about how best to manage rage with medications and talking therapies? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr D, a 47-year-old Army military police officer veteran with multiple combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, had been exposed to repeated blasts that led to mild traumatic brain injuries (TBIs). His symptoms worsened over several years after his deployment and transitioning out of the military, and he was diagnosed with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Mr D presented for an evaluation of severe anger and rage that interfered with his relationships and job performance (working nights at a home improvement store, as he preferred the isolation provided by nighttime shifts that allowed him to avoid interacting with others). He endorsed insomnia, frequent nightmares, and increasing tension with his wife, which led to heated arguments. He often feels overwhelming frustration and anger, particularly when dealing with situations that trigger memories of betrayal or a lack of support during his military service.

In addition to his PTSD symptoms, Mr D admitted to using alcohol to cope with his distress. He described becoming enraged easily when he felt slighted by others, particularly in social situations (eg, at bars or when driving). He reported several instances of “road rage,” in which he became aggressive toward other drivers when he perceived their disrespect (eg, not letting him merge lanes). Mr D said he had been prescribed sertraline (200 mg/day) and tramadol (150 mg/day) to address his PTSD and postinjury pain. However, he experienced a seizure on this regimen, which led to a moderately severe TBI. Since that incident, he has felt betrayed by that health care provider and has harbored resentment over the treatment that contributed to his seizure and the worsening of his symptoms.

Mr D’s anger episodes often feel uncontrollable, and they leave him with deep regret. His problematic behavior has strained his marriage, and his wife has expressed concern that his temper is increasingly unmanageable. He recognizes that his outbursts are adversely affecting his personal and professional life, and after a particularly intense argument with his wife and a close call with road rage, he decided to seek professional help to regain control over his emotions and to restore balance in his life.

DISCUSSION

What Are Rage and Rage Reactions?

“Sing, Goddess, of the wrath of Achilles.”1 The Iliad, western culture’s oldest surviving written work, opens not with love, loss, faith, or fear—but rage. From Achilles’ battle fury to the Marvel comic character the Incredible Hulk, the uncontrollable and transformative power of rage has echoed throughout history. In modern times, the Hulk’s involuntary transformation—punctuated by the tagline “You wouldn’t like me when I’m angry”—illustrates rage’s ability to transform reason and character.

Rage, wrath, and fury are words used to describe the extreme end of irritability. Irritability is comprised of anger (the affective portion) and aggression (the behavioral portion).2 Anger has a negative emotional valence, meaning that it is unpleasant. In its extreme, anger provokes aggressive behaviors that appear reactive or lacking inhibition via cognitive processes.3 Unlike other negative emotions (eg, fear or sadness) that are associated with withdrawal or flight, anger promotes approach and anger as well as arousal of the autonomic nervous system,4 with increases in heart rate, muscle tone, adrenal release, and characteristic facial expressions of a clenched jaw and furrowed brow.3 Loss of control of behaviors and thoughts characterizes rage as transcending frustration, annoyance, or the whims of a child’s tantrum.5

What Distinguishes Rage From Anger, Irritation, and Impulsivity?

Irritability and impulsivity can be viewed as characterological traits. However, rage is an extreme form of anger that is associated with a transient reduction or loss of thought and behavioral control. Anger is the affective component of irritability.2 Irritability, as a dimension of personality, is defined as the tendency to become angry and reactive to slight provocations and disagreements.2 Irritability is a normative trait that is widely experienced, decreases with age, and is associated with disrupted functioning.6 In the Great Smoky Mountains Study, roughly 90% of the 1,420 participants (aged 9–16 years) reported experiencing irritability; there was no observed difference due to gender.6 Across cultures, facial expressions observed during anger are identifiable and are even displayed by congenitally blind children.3

Impulsivity differs from rage in that it is a behavioral predisposition rather than an emotional state. Impulsivity leads to a pattern of swift actions without consideration of the consequences (negative or positive) of the actions for themselves or others.7 Impulsive behaviors may be related to a lack of planning, risk-taking, and rapid decision-making.7 Impulsivity is related to rage through impulsive or reactive aggression. In the context of extreme anger, aggression can be perpetrated reactively or impulsively, even in those without high impulsivity, bypassing the usual cognitive inhibitions.3

What Triggers Rage?

Anger and aggression can be provoked by a variety of stimuli (eg, frustration, verbal insults, failure to receive an expected reward, or failed attempts to avoid punishment).2 Anger is viewed as an adaptive emotional response that has survival benefits by preparing individuals to face confrontation.3 Rage is triggered when an emotional response to a stimulus is so extreme that the usual barriers to aggressive behaviors are overcome or circumvented. This can be the result of imminent or inescapable threats, or when other factors reduce a person’s tolerance to irritation or their ability to control behavior. Chronic interpersonal violence is an established trigger of rage, especially when perceived threats mirror past dangers. In State v Leidholm (1983) and later in State v Kelly (1984), the defense of battered woman syndrome helped establish a legal precedent for a trauma-informed view of self-defense. These legal cases highlighted the notion that behaviors performed during a rage response and that appear unreasonable can be seen as subjectively reasonable when considered within the individual’s limited ability to control thought and behavior during a trauma-induced rage reaction.8,9

Rage is associated with conditions linked with low distress tolerance, increased impulsivity, or altered cognitive patterns. Rage is specifically mentioned in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision, in the discussion of several psychiatric disorders. For example, individuals with borderline personality disorder may experience rage in response to intolerable feelings of abandonment or emptiness.10 In narcissistic personality disorder, humiliation or shame, which is especially hurtful when ego integrity is threatened, may lead to rage responses.10 Rage is also noted in disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD), in which youth display developmentally abnormal emotional reactivity and behavioral control.

The triggers of rage—whether provoked by external inescapable dangers or internal intolerable perceptions—vary greatly. Responses to triggers also differ among individuals and within the same person over time, modified by varied levels of distress tolerance and the emotional context in which a triggering stimulus can be interpreted.

Which Neuroanatomical Structures and Circuits Regulate Rage?

Rage and anger are mediated by interactions between limbic structures that are responsible for affective arousal and cortical regions that are involved in the regulation of social behavior. When Klimecki and colleagues11 investigated real-time experiences of anger and punishment using an ecologically valid provocation paradigm, they found that self-reported anger was associated with activation in the amygdala, the superior temporal sulcus, and the fusiform gyrus—each of these regions is involved in emotional salience, social cognition, and facial processing. Increased activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) during provocation predicted participants’ ability to inhibit punishment later, implicating these regions in emotion regulation and social decision-making.11 This dissociation among circuits that underlie anger and those involved in aggressive behavior highlights the importance of frontolimbic integration in the modulation of rage.

Sorella and colleagues12 further identified distinct structural and functional networks associated with trait anger and anger control. Using an unsupervised machine learning approach, they found structural correlates of trait anger in grey matter concentrations within the ventromedial temporal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, fusiform gyrus, and cerebellum—regions implicated in attentional bias toward aversive stimuli and hostile attribution tendencies. At a functional level, higher temporal frequency activity within the default mode network (DMN) was associated with greater anger control, supporting the DMN’s role in introspective and self-regulatory emotional processing.12

Together, these findings suggest that rage is mediated by a distributed network that involves limbic structures (eg, the amygdala and ventromedial temporal cortex) for emotional arousal and appraisal, and cortical regions (eg, the DLPFC, ACC, and DMN) for regulation and inhibition of aggressive responses. This integrative network enables individuals to experience anger while modulating behavioral outputs that are based on social context and internal regulatory capacity.

Which Psychiatric and Neuropsychiatric Conditions Are Characterized by Rage Reactions?

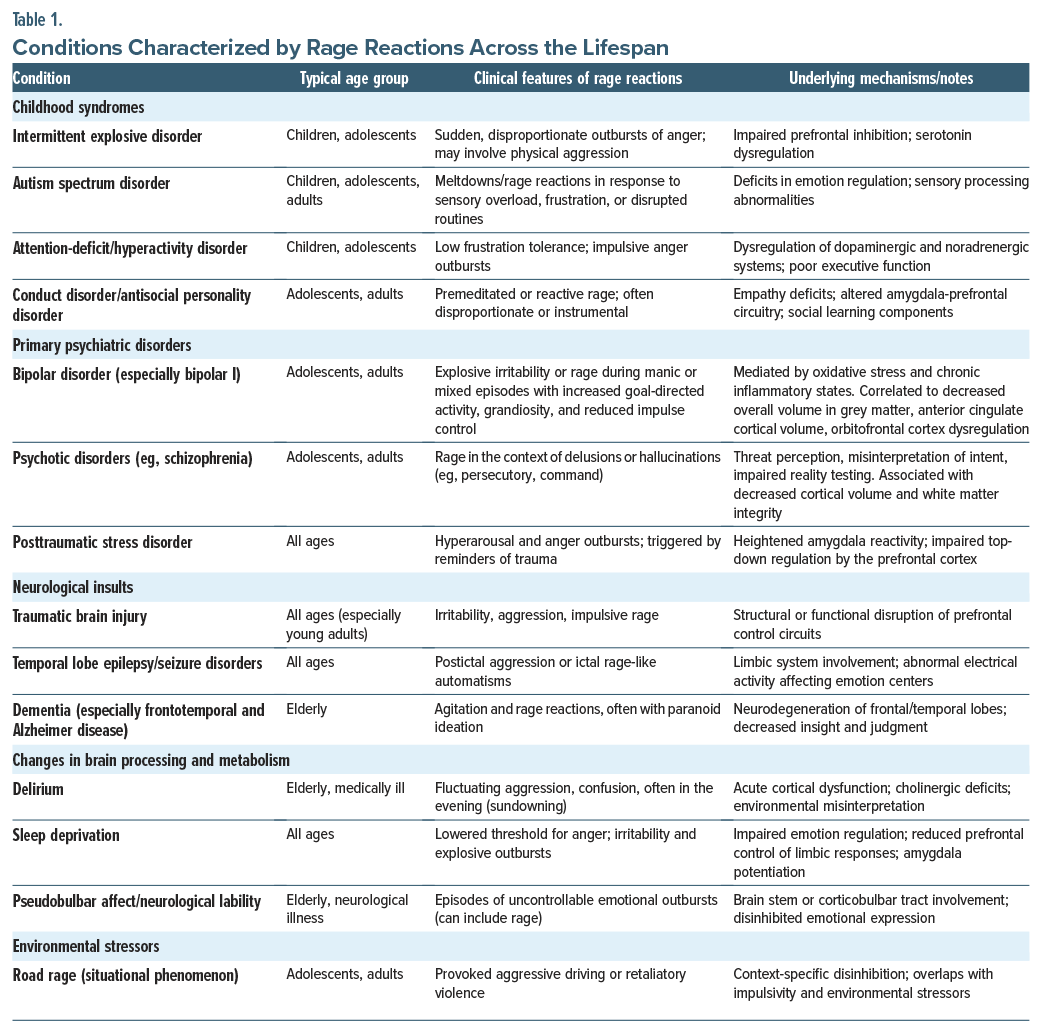

Table 1 catalogues psychiatric and neuropsychiatric conditions associated with rage reactions across the lifespan, revealing distinct patterns of underlying pathophysiology and clinical presentation. While rage reactions manifest across diverse conditions, they often involve disruption of normal prefrontal-limbic regulatory circuits.13

Childhood syndromes including intermittent explosive disorder (IED), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) demonstrate rage reactions stemming from impaired prefrontal inhibition, sensory processing abnormalities, and executive dysfunction, with mechanisms involving serotonin dysregulation and dopaminergic-noradrenergic system imbalances.14 Primary psychiatric disorders in adolescence and adulthood, particularly bipolar disorder and psychotic disorders, exhibit rage reactions mediated by oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, and structural brain changes that include decreased gray matter volume and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) dysregulation,15,16 while PTSD-related rage involves heightened amygdala reactivity with impaired top-down prefrontal regulation.14

Neurological insults across age groups demonstrate rage reactions through direct disruption of neural circuits, with TBIs affecting prefrontal control systems and temporal lobe epilepsy involving limbic system dysfunction.17,18 Various forms of dementia can disinhibit individuals through neurodegeneration of frontal-temporal regions, with the potential additive insult of paranoia and a lack of reality-testing abilities.13 Environmental and metabolic factors further contribute to rage reactions, including delirium’s acute cortical dysfunction with cholinergic deficits, sleep deprivation, and pseudobulbar affect’s disinhibited emotional expression through brain stem involvement.19,20

How Might Rage Reactions Be Evaluated?

Although there is no formal strategy for evaluating rage reactions, taking a thorough history that considers underlying neuropsychiatric conditions and comorbid conditions (eg, substance use) can assist in understanding rage reactions.

Neuropsychiatric Disorders

Episodes of rage are common in several biological (eg, TBI, intellectual impairment) and psychological (eg, personality traits and disorders, mood disorders) conditions. During normal development, children learn how to regulate emotions through conscious (eg, identifying emotions, recognizing a need to regulate feelings, learning and incorporating coping skills) and unconscious processes. Individuals who suffer from intellectual disabilities are often hampered by impairments in cognition and communication that can interfere with emotional processing and regulation and lead to poor insight into social situations, disinhibition, and impulsivity.21

Emotional dysregulation commonly follows acquired brain injuries.22 Lesions within the frontal and temporal lobes, as well as impairments in communication, visual perceptual memory, and executive function, are associated with irritability, anger, and aggression.23

Personality Traits

Rage and impulsive aggression are features of many mood disorders, personality disorders, and nonpsychiatric conditions.24,25 Road rage is associated with thrill-seeking while driving, intolerance with discomfort, and impulsivity.24

Substance Use

Individuals who use psychoactive substances are prone to state-trait anger as well as a greater intensity and frequency of anger, as compared to nonuser controls.26 Such symptoms may also be worsened by acute drug withdrawal and imbalances within reward system pathways. Repeated exposures to psychoactive substances can damage brain regions that are associated with inhibitory control, reward, motivation, and learning, which predisposes to impulsive aggression.26

Considering a Timeline

Rage reactions are often provoked by a stimulus (eg, a perceived threat or aversive stimulus).27 The manifestations of rage vary in large part due to what has precipitated rage, in what context rage has been provoked, who or what provoked the rage reaction, and where one was when rage struck. In addition, the treatment of rage is predicated on its etiology (eg, biological, psychological, or cultural factors), as detailed previously. Unfortunately, there is no reliably predictive course of rage across the lifespan. However, many individuals learn to anticipate the circumstances in which rage often erupts, and this can lead to preventive and modulatory strategies that mitigate its negative sequelae.

Once an individual perceives a stimulus as aversive or threatening, the anterior insula, amygdala, and thalamus become activated, triggering interoception, autonomic arousal, and activation of a stress response. Gender also plays a role in rage responses (eg, men diagnosed with borderline personality disorder have stronger amygdala reactivity than women with borderline personality disorder and healthy control men when provided with a script-driven image of physical aggression and interpersonal rejection).27 In individuals with an IED, there is less white matter integrity in frontal and temporoparietal regions, as well as a lower volume of gray matter in the OFC, ventromedial prefrontal cortex, ACC, uncus, insula, and amygdala.27

How Might Rage and Rage Reactions Interfere With Intrapsychic and Interpersonal Functioning and With Academic and Work Performance?

Anger and rage are thought to be delineated into intrapersonal anger that is the internal sensation of being angry and interpersonal anger or the effects of one’s display of anger on others. Simulated interpersonal experiments demonstrate that intrapersonal anger breeds a competitive stance from the angry individual and can lead to retaliatory behaviors, selfishness, and aggression.28 In economic bargaining models, intrapersonal anger negatively impacted social relationships during negotiations, reduced rational judgments, and increased punitive decision-making.29 Those on the receiving end of workplace aggression have reduced task-specific and contextual performance thought to be mediated by reduced job satisfaction and organizational commitment as well as diminished psychological and physical health.30

In education, anger and other negative emotions are thought to reduce achievement through several factors: attentional diversion from school, direct reduction in higher-order cognitive processes, decreased motivation for learning and reduced engagement, and challenges in developing and maintaining relationships in the classroom.31 Additionally, aggressive children and adolescents are at greater risk for school maladjustment, poor school performance, and lower educational attainment. This held true even when controlling for genetics, sex, and environmental effects through the analysis of >27,000 twins across 4 European countries.32

On a neurobiological level, functional magnetic resonance imaging of male soldiers after an anger-inducing activity demonstrated a residual increase in functional connectivity between the amygdala and the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (which normally exerts control over emotional reactivity through regulation of the amygdala and insula), and this connectivity was positively associated with smaller right IFG volume, higher trait-anger level, and more traumatic stress symptoms.33 Thus, in this population, it appears that anger can create lasting neurological changes associated with maladaptive recovery and potentially predispose those with anger to long-term stress symptomatology.

Rage rarely leads to enhanced relationships. However, in some circumstances, rage may facilitate efforts at self-defense (eg, as occurs when a child is threatened and a parent defends them with little regard for their personal safety). In health care settings, rage can disrupt interpersonal relationships (eg, between patients and providers and among staff), lead to treatment nonadherence, and provoke workplace violence. Cross-culturally, rage is typically manifested with the same intensity and scope of behavioral variations (eg, yelling, hitting, appearing to be out of control); however, cultural expectations for what is considered acceptable behavior differ among countries.

How Can Rage Be Managed?

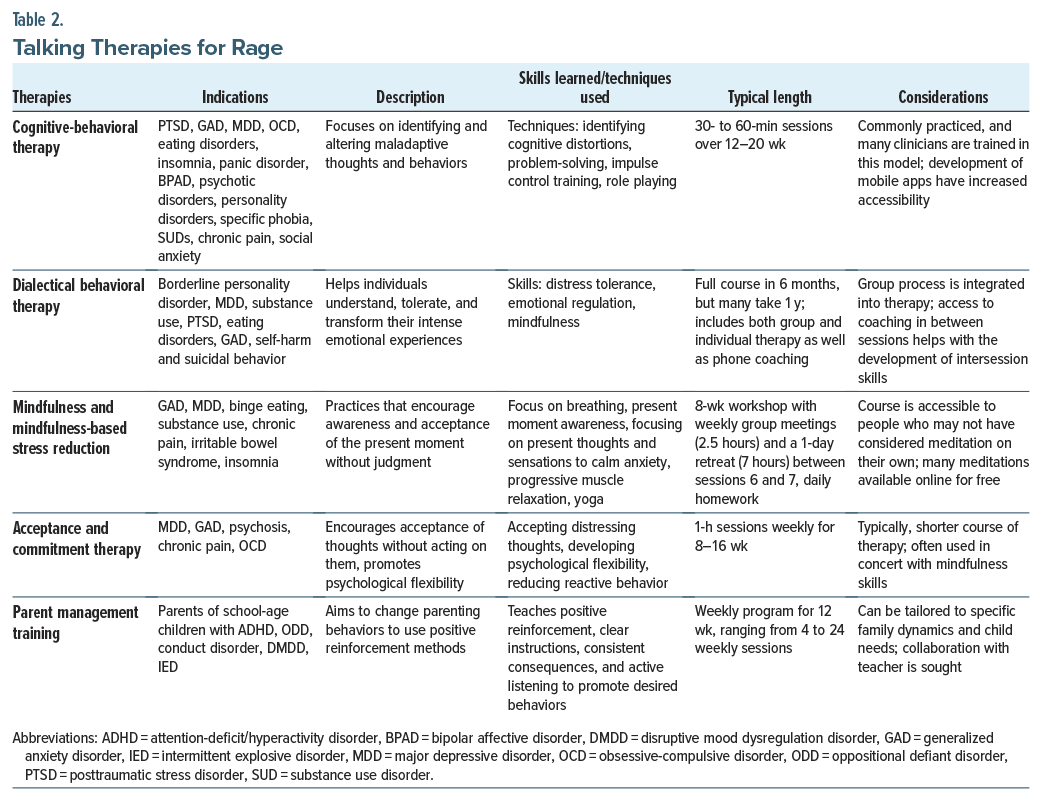

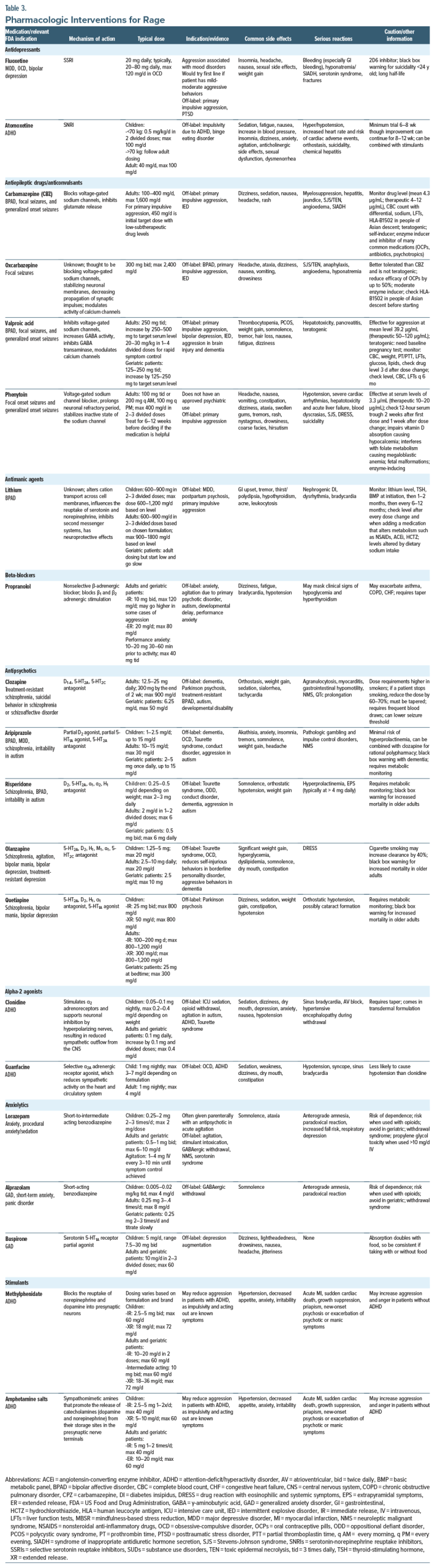

The treatment of rage is predicated on identifying its underlying etiology—whether biological, psychological, or cultural—making timely evaluation of rage-inducing precipitants crucial. Knowledge gained from such assessment can guide individualized management approaches. The management of anger, aggression, and rage often involves use of behavioral strategies, anxiety reduction techniques, and pharmacologic interventions. Unfortunately, guidance on this topic has been limited, given that anger and aggression are symptoms of a bevy of psychiatric illnesses, and criteria for anger have not been established. This has limited the development of high-quality evidence.34 Table 2 and Table 3 summarize psychotherapeutic and pharmacologic interventions (eg, the duration of psychotherapy, medication dosing, medication side effects, and relative contraindications of prescription drugs), respectively.

Psychotherapeutic and Behavioral Approaches for Anger, Irritability, and Rage

Although guidelines are lacking, a variety of behavioral and psychotherapeutic interventions have been studied regarding the treatment of aggression. Nevertheless, using a patient-centered approach helps patients navigate psychotherapeutic treatment options.

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) effectively manages aggressive behaviors because it identifies and changes the thoughts, emotions, and behaviors that fuel anger. CBT helps individuals understand the causes of their rage, develop healthier thinking patterns, and learn coping strategies to prevent outbursts. CBT is widely used for an array of psychiatric disorders (eg, mood disorders, personality disorders, insomnia, PTSD, eating disorders, and primary psychotic disorders). Moreover, CBT is the most studied treatment for anger and aggression, with behavioral interventions showing greater efficacy than cognitive interventions alone.34

Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

Dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT) was designed for patients with borderline personality disorder who engage in self-injurious behaviors; it teaches individuals how to recognize, regulate, and respond to intense emotions (eg, anger and rage) and aggressive behaviors (eg, yelling, threatening others, being violent, and demonstrating hostility) in healthier ways.35,36 Through enhancing mindfulness, distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and skills involved in interpersonal effectiveness, DBT reduces the intensity and frequency of angry outbursts.36,37 DBT encourages a balance between accepting difficult emotions (eg, anger) and taking concrete steps to transform them, which leads to more effective emotional regulation and healthier relationships. DBT is especially useful when addressing self-directed impulsive, aggressive acts (eg, cutting or making suicide attempts). An advantage of DBT is that it combines multiple treatment modalities (eg, group process, individual therapy, after-hour phone coaching, skills classes, and homework). However, it is time-intensive, as treatment often takes up to a year to complete the program.

Mindfulness and Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

Mindfulness manages rage and anger by fostering awareness, acceptance, and a nonjudgmental attitude toward one’s emotions. Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is a structured mindfulness-based program designed to reduce stress that can treat anxiety, depression, binge eating, and substance use. Mindfulness empowers individuals to observe their anger without being controlled by it, to regulate anger’s physical manifestations, and to make more deliberate and value-aligned choices rather than acting impulsively. Meditation mitigates the physiological stress response, which is helpful when experiencing intense emotions; it promotes relaxation and facilitates thinking about how to respond to overwhelming feelings. Over time, mindfulness cultivates emotional resilience, which allows individuals to experience and process anger without it overwhelming them. MBSR programs are highly structured. They involve weekly 2.5-hour group sessions, homework, and a 1-day retreat. Although many MBSR programs are expensive and are not covered by health insurance, low-or no-cost options are available. Acceptance-based therapies, like mindfulness and acceptance and commitment therapy, complement cognitive approaches by underscoring that anger is transient and may not require behaviors that are based on anger.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy

Acceptance and commitment therapy reduces rage and anger by accepting emotional experiences, rather than by avoiding or suppressing them, defusing the power of anger-driven thoughts, and choosing value-based actions that align with one’s goals and identity. Instead of attempting to eliminate anger and rage, ACT facilitates a healthier, more flexible relationship with emotions, which leads to more constructive responses that are aligned with their broader life values. As with mindfulness, ACT favors the acceptance of emotions, which creates time between the recognition of anger and action. ACT has been efficacious in children, adolescents, and adults.38,39

Parent Management Training

Parent management training (PMT) is based on the principles of operant conditioning. It was designed for parents of school-age children with emotional dysregulation and aggressive behaviors (eg, those with ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], conduct disorder [CD], DMDD, or IED). PMT helps parents manage their child’s challenging behaviors by teaching them positive reinforcement techniques, psychological flexibility, and strategies to combat reactive behavior.40,41 PMT typically takes less time than psychotherapy, and it is often used in combination with mindfulness skills.

Pharmacotherapy for Anger, Irritability, and Rage

Pharmacologic interventions for the management of anger, irritability, and rage are beneficial, particularly when behavioral strategies alone are insufficient or when aggression is emblematic of a psychiatric or neurological condition. Although no medications have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for anger or rage, many medications are used off-label for this purpose. When selecting a pharmacologic agent, the cause of the aggression or anger should be considered (eg, an under-or untreated psychiatric condition or neurological issue [eg, TBI, dementia]), as it will guide the choice of medication. Some medications (eg, benzodiazepines) are best used for acute aggression, given their risk of long-term side effects and drug dependency, while others are well suited for chronic management. Further, the individual’s ability to adhere to medication (eg, lithium, valproate, and clozapine) monitoring should be determined. Finally, given the possibility of drug-drug interactions, coadministration of other agents as well as their hepatic and renal function should be considered.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants mitigate rage by targeting the underlying mood disturbance that contributes to emotional dysregulation. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which increase serotonin concentrations in the synaptic cleft, are the most prescribed drugs for primary mood disorders. Rage is a core symptom of several conditions (major depressive disorder [MDD], anxiety disorders, and borderline personality disorder) that are frequently a manifestation of emotional dysregulation. In these conditions, patients may have exaggerated emotional responses to minor triggers, with anger that escalates quickly into rage.

Antidepressants provide significant relief from rage, particularly when it is linked to depression, anxiety, PTSD, or other psychiatric disorders. Depression often co-occurs with irritability, frustration, and anger, which can manifest as rage. Common neuropsychiatric symptoms of depression (eg, sleep disturbances, fatigue, brain fog, and impaired concentration ability) can exacerbate irritability and contribute to frustration and rage. Conditions like generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) or PTSD are often manifest by irritability and anger. When rage is associated with anxiety disorders or PTSD, antidepressants can help by addressing symptoms of anxiety or trauma. SSRIs are also recommended for the management of behavioral symptoms of dementia and titrated to a maximum dosage before prescribing a medication (eg, an antipsychotic, valproate) with more disturbing side effects. While psychostimulants are a first-line treatment for ADHD, the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) atomoxetine can reduce oppositional behavior in children with ADHD.42 By treating the cause of the rage, antidepressants can help reduce the intensity and frequency of angry outbursts.

Fluoxetine is the most studied antidepressant for the management of anger, irritability, aggression, and rage. SSRIs tend to be more effective than SNRIs in reducing anger and aggression. Generally well-tolerated, fluoxetine’s side effects include sexual dysfunction and weight gain. Despite mixed results, fluoxetine has been recommended as a first-line treatment for mild-moderate anger and aggression.42,43 Fluoxetine can inhibit platelet aggregation, which raises the risk of bleeding, although this is rarely clinically significant. Fluoxetine is also a cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 inhibitor and may interact with medications (eg, warfarin).

Antiepileptic Drugs and Anticonvulsants

Antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) and anticonvulsants are primarily used to treat seizure disorders, but they are also prescribed off-label to manage mood lability, aggression, irritability, and rage due to their γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)–enhancing and glutamate-reducing activity. Several AEDs, along with fluoxetine, have strong evidence that supports their use in treating impulsive aggression.42 The typical target dose for aggression is lower than the doses typically used for seizures or bipolar disorder (eg, for carbamazepine, phenytoin, and valproate).43

Carbamazepine has repeatedly demonstrated efficacy in reducing impulsive behaviors (in ADHD, dementia, seizure disorders, mood disorders, and schizophrenia). Its target dose for aggression is 400–800 mg/d, with a target serum level of 3–5 μg/mL.43,44 However, carbamazepine’s use is limited by its teratogenic effects and its ability to act as an inhibitor and inducer of many medications, including oral contraceptive pills (OCPs), antibiotics, antineoplastic agents, and other psychotropics, as well as itself. Given the strength of the evidence that supports carbamazepine for impulsive aggression, if no clear psychiatric condition is identified, it is worth considering empiric treatment with carbamazepine or lithium. Oxcarbazepine is a better-tolerated, although potentially less effective, alternative to carbamazepine. Its dosing typically ranges from 1,200 to 2,400 mg/day.43 While oxcarbazepine is a less potent enzyme inducer than carbamazepine, it still reduces the efficacy of OCPs. Both oxcarbazepine and carbamazepine convey a risk of developing Stevens-Johnson syndrome.

Valproate is often used adjunctively to manage aggression, particularly in cases of TBI, dementia with behavioral disturbance, developmental disability, and schizophrenia. Valproate can be administered orally, intravenously, or in sprinkle formulations, which provides flexibility for patients and clinicians. For aggression, dosing typically starts at 250 mg 3 times/day for adults, although higher doses (up to 20 mg/kg in divided doses) may be used. When studied in those with IED, the mean effective valproate blood level was 39.2 μg/mL (normal dose range, 50–120 μg/mL).43 Although valproate has been used for dementia with behavioral disturbance, the evidence and safety of valproate are less than those of the 2 recommended antipsychotics for behavioral dyscontrol, aripiprazole and risperidone.45 Valproate is a potent teratogen, and this medication should be used with caution in women of childbearing age. Serious side effects include hyperammonemia, hepatotoxicity, and pancreatitis. Due to valproate’s significant side effects and its relatively weaker body of efficacy evidence in agitation and rage, valproate is often viewed as a second-or third-line agent for the management of agitation.

Although phenytoin is not FDA-approved for psychiatric indications, it shows promise for reducing impulsive aggression, with one study reporting a 71% reduction in aggressive behaviors.43 When used for aggression, phenytoin’s average blood level was 3.3 μg/mL (therapeutic range, 10–20 μg/mL). Phenytoin can cause serious adverse reactions (eg, cardiac arrhythmias, hepatotoxicity, blood dyscrasias, acute liver failure, and drug reaction) with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, which limits its use.

Lithium

Lithium is an FDA-approved antimanic agent used for mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. While its mechanism of action for mood stabilization and antiaggressive effects is not fully understood, lithium is believed to work through regulation of serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine, and GABA; inhibition of the breakdown of inositol; enhancement of prefrontal cortex function; and promotion of neuroplasticity. Lithium’s antiaggressive effects have been well documented, particularly in those with personality disorders, schizophrenia, and MDD. Lithium can also reduce aggression and prevent suicidal behaviors.44 It is also included in treatment algorithms for IED, where, along with carbamazepine, it is considered a first-line treatment for those with severe, problematic episodes.43

Use of lithium requires careful monitoring for tremors, cognitive slowing, gastrointestinal upset, polyuria, and polydipsia. Regular blood monitoring is essential to ensure that lithium levels remain within a narrow therapeutic range, so that toxicity can be avoided. Because of this, lithium is not recommended for those who cannot commit to regular blood draws or who consume alcohol regularly. Caution is also advised when coadministering lithium and thiazide diuretics, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, as these can raise lithium levels and cause toxicity. Lithium’s teratogenic effects (eg, Ebstein anomaly) are well documented, although recent literature has suggested that careful monitoring of lithium use during the first trimester of pregnancy may be considered if the benefits of therapy outweigh the risks of cardiac malformations.43

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers, such as propranolol, are competitive antagonists of noradrenaline and adrenaline at β-adrenergic receptors. These medications are often used off-label to manage behavioral symptoms of aggression and agitation, particularly when they are driven by activation of the sympathetic nervous system. By reducing signs and symptoms (eg, tachycardia, elevated blood pressure, and tremulousness), beta-blockers can alleviate the physical discomfort that often intensifies rage.

Propranolol is commonly used off-label for anxiety, particularly performance anxiety, and it can also aid in reducing impulsive aggression. The dosing range for propranolol is broad, and patients may experience hypotension or bradycardia before the medication begins to show therapeutic effects. It may be prescribed in relatively high doses for adjunctive treatment of agitation associated with primary psychotic disorders, ASD, or developmental delay; use is limited only by its cardiac side effects. A recent randomized controlled trial using high-dose propranolol for severe and chronic aggression in ASD showed a 50% reduction in aggressive behavior as measured by 2 behavioral scales, and the dose was either stopped with a therapeutic response or titrated to a maximum of 200 mg 3 times/day.46 Notably, no participants had to drop out due to cardiac effects. Common side effects of beta-blockers include hypotension, fatigue, dizziness, and sexual dysfunction.

Antipsychotics

Antipsychotics modulate the activity of serotonin and dopamine, 2 neurotransmitters that are critical for the regulation of mood and emotional responses. Overactivity of dopamine, particularly in the mesolimbic pathway, is associated with irritability, agitation, and aggressive behavior. D2 receptor blockade reduces dopamine signaling and alleviates these disruptive symptoms. Serotonin also plays a key role in mood regulation, and dysregulation can contribute to mood swings, irritability, and aggression. Antipsychotics, often combined with benzodiazepines or antihistamines, are the mainstay for the treatment of acute agitation in primary psychotic disorders as well as for emergent, undifferentiated agitation.

Antipsychotics are commonly used to treat agitation and aggression in conditions like bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and borderline personality disorder, each of which involves emotional dysregulation and behavioral disinhibition. Antipsychotics may be used adjunctively in MDD, particularly when there is severe agitation, irritability, or psychotic features. In patients with ASD or intellectual disabilities, irritability and aggression are common. Two antipsychotics, aripiprazole and risperidone, are FDA approved for the management of irritability in ASD. Aripiprazole is often preferred as a first-line option due to its more favorable side effect profile and lower risk of metabolic syndrome, making it better suited for long-term use. Risperidone has good evidence for use in children with oppositional behavior and aggression with and without ADHD, ASD, or developmental disability.47 Both aripiprazole and risperidone are used off-label for aggression and agitation in behavioral symptoms of dementia. While aripiprazole and risperidone have similar efficacies for dementia, aripiprazole has fewer side effects and is often prescribed first.45 However, akathisia is a common and often debilitating side effect of aripiprazole. In addition, aripiprazole’s dopamine agonism may increase impulsivity, which could be problematic in aggressive individuals. Side effects of risperidone include hyperprolactinemia and extrapyramidal symptoms, orthostasis, and weight gain.

Olanzapine and quetiapine are also used to manage aggression, although they have relatively less supporting evidence and may have more side effects than aripiprazole or risperidone. Olanzapine is effective for reducing aggression and irritability in mania and is a useful antimanic agent. It has also been shown to reduce self-injurious behaviors in borderline personality and aggression in dementia patients, although its long half-life limits its use in those with hepatotoxicity.44 Quetiapine, commonly used off-label for dementia with behavioral disturbances and hyperactive delirium, carries a higher risk of orthostasis compared to first-line antipsychotic agents, like aripiprazole and risperidone. Quetiapine is also used in the treatment of CD, although evidence for pharmacotherapy in CD is lacking.

Clozapine is specifically indicated for the management of suicidal behavior and aggression in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and it is often used with psychosis in Parkinson disease. Clozapine can be used off-label for aggression in ASD or developmental disability. It has been shown to be more effective than haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine in reducing hostility and aggression, independent of its antipsychotic properties.44 However, clozapine may cause significant orthostasis, requires weekly blood draws to monitor for the risk of agranulocytosis, and can cause myocarditis and gastrointestinal hypomotility, and its levels can be affected by nicotine use, as it is a substrate of CYP1A2. As of late 2024, the FDA has recommended that the clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy database is no longer needed, which removes barriers to accessing care.

A meta-analysis found that antipsychotics are broadly effective for aggression, although the effect size was small and side effects were significant.48 Overall, antipsychotics reduce aggression related to primary psychiatric disorders, but evidence is limited for impulsive or disruptive behaviors in the absence of an underlying condition. Moreover, the risk of antipsychotics causing metabolic syndrome and cognitive dysfunction from long-term use is elevated, and it requires metabolic monitoring. Third-generation antipsychotics, eg, aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine, which act as dopamine partial agonists, may paradoxically increase impulsivity.49

Alpha-2 Agonists

Alpha-2 agonists, eg, clonidine and guanfacine, stimulate α2 adrenergic receptors in the brain, leading to a reduction in norepinephrine release and balancing autonomic tone. These medications are particularly effective in managing aggression and impulsivity in ADHD, anxiety, PTSD, and substance withdrawal. Alpha-2 agonists may be of benefit in those with ADHD who experience more anger, aggression, or impulsive rage with a stimulant.

Both clonidine and guanfacine, whether used as monotherapy or adjunctively, improve symptoms of ADHD, eg, focus, impulse control, and frustration tolerance, thereby reducing outbursts of anger and aggression. Clonidine can be particularly useful in children, as it is available in a transdermal formulation. Although commonly comorbid, clonidine has limited evidence for treating aggressive behavior in children with ODD.40 Clonidine is commonly used in opioid withdrawal protocols to manage both the physiological symptoms of withdrawal and associated irritability. It may also be prescribed to mitigate autonomic symptoms in PTSD, although a recent systematic review highlighted significant study heterogeneity.50 Guanfacine has similar off-label uses, may be slightly more likely to diminish aggressive behavior than clonidine, and is less likely to cause hypotension, making it a better option for those who are sensitive to the hypotensive effects of clonidine.40

Anxiolytics

Disorders of anxiety and mood often trigger irritability and emotional dysregulation and angry outbursts. By reducing anxiety and its physical manifestations, anxiolytics, eg, benzodiazepines and buspirone, can calm emotional states and prevent them from escalating into aggression.

Benzodiazepines are rapidly acting anxiolytics that increase the frequency of GABA-A receptor opening. These medications are effective for acute anxiety (eg, panic attacks) and acute aggression, such as with stimulant or dissociative intoxication. Some of these agents are available in parenteral formulations for emergency use; however, they should generally be prescribed for short-term use due to the risk of tolerance, dependence, and respiratory depression. For long-term management of aggression associated with anxiety, SSRIs, SNRIs, or buspirone are preferable. Benzodiazepines, like lorazepam and alprazolam, can reduce agitation and rage in the acute setting. Lorazepam is available parenterally, sometimes in combination with antipsychotics, to manage acute agitation. Alprazolam is commonly used for panic attacks, which can resemble rage or aggression, particularly when triggered by a perceived threat. However, due to the potential for dependence, these medications should not be used for extended periods.

Buspirone, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, provides anxiolysis without the sedating effects or dependency risks associated with benzodiazepines. FDA approved for GAD, buspirone is generally well tolerated without inducing serious side effects. It is absorbed better when it is taken with food.

Stimulants

Stimulants reduce rage and aggression primarily by improving impulse control, emotional regulation, and frustration tolerance through the increased activity of dopamine and norepinephrine. These medications are helpful in ADHD, where poor attention, emotional dysregulation, and impulsivity contribute to aggressive behaviors. By enhancing cognitive function and emotional reactivity, stimulants help individuals manage stress and frustration, thereby reducing the likelihood of outbursts. Stimulants are considered first-line treatment for the aggression and impulsivity commonly seen in ADHD. Methylphenidate works by blocking the reuptake of norepinephrine and dopamine into presynaptic neurons, while amphetamine salts are sympathomimetic amines that promote the release of both neurotransmitters. As a result, addressing the underlying ADHD symptoms often helps manage aggression associated with the disorder.40,51

While stimulants are highly effective for ADHD-related aggression, they should be used cautiously in those without ADHD, as they may exacerbate aggression or impulsive behaviors. Stimulants can also lead to increased anxiety or irritability, especially in those with bipolar disorder or an anxiety disorder. Close monitoring is essential, particularly for individuals who are sensitive to stimulants’ effects (eg, insomnia, appetite suppression, and increased heart rate, with growth suppression being a potential long-term concern in children). Given these risks, stimulant use should be managed carefully, particularly in those with co-occurring mood disorders, anxiety, or a history of substance abuse.

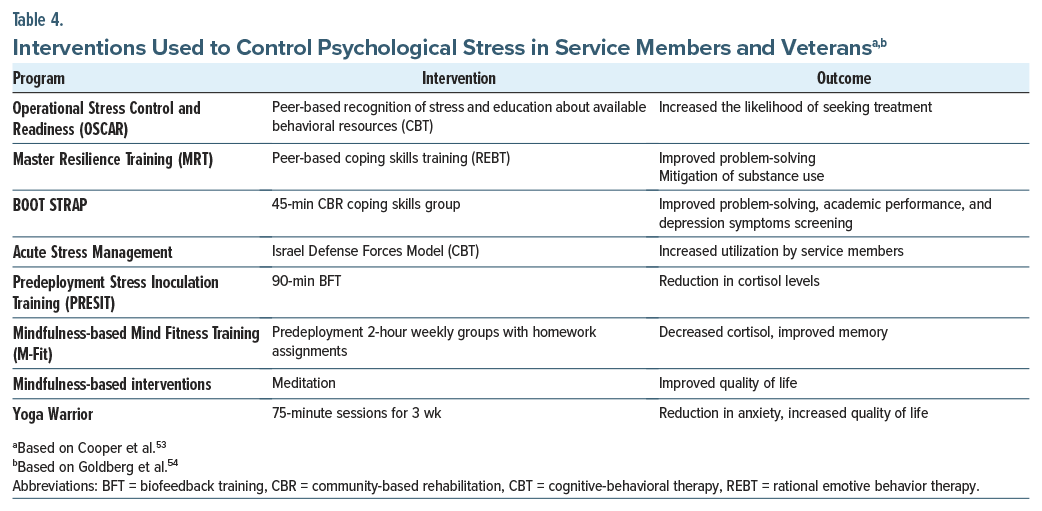

How Can the Control Over Intense Emotions Be Taught?

Many rage management strategies focus on identifying anger, restructuring thoughts, modulating anger, and practicing alternative ways to manage strong emotions.52 Several interventions (eg, CBT, rational emotive behavior therapy, biofeedback training) help those in the military regain control over their intense negative emotions (Table 4).53,54 Using nonpharmacologic treatments can further support the psychological and physical health of veterans.54

What Can We Learn From How Rage Is Portrayed in Television and the Movies?

Rage (which is often conceptualized as an emotion or as a behavior) frequently serves as a catalyst for violent or volatile actions.55 Stephen King’s “Rage” recounts the story of Charlie Decker, a high school student who “loses his mind” and becomes a school shooter.56 Bruce Banner is a mild-mannered, introverted scientist with a troubled past, who after a laboratory accident becomes transformed into a green monster (the Hulk) when provoked by anger.57

Rage is becoming a legitimized method of emotional expression and a feared outcome of interpersonal exchanges. The portrayal of rage in the media challenges the civilized notion that all discourse must remain polite when discussing opposing views.55 While some media reveal rage as manifestations of artistic productions and political activism, others display rage as violent and volatile.55

What Happened to Mr D?

Mr D appreciated having a comprehensive evaluation provided by the brain injury medicine specialist. For the first time, he was offered a framework that explained how the combination of high-dose sertraline and tramadol may have contributed to his seizure, which resulted in a moderately severe TBI. This understanding helped him to reframe his experience as the outcome of a pharmacologic side effect in the setting of an underlying vulnerability from TBI and PTSD, rather than as a personal failure or betrayal.

Although he was initially resistant to starting any new psychiatric medications, Mr D was open to exploring alternative treatments. Given the severity of his irritability and aggression, as well as his self-reported use of alcohol to manage emotional distress, the use of anticonvulsants for mood stabilization and the potential benefit of medications targeting alcohol cravings were discussed. After reviewing medication options (eg, valproate, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and gabapentin), Mr D chose to start oxcarbazepine, favoring its relatively mild side effect profile compared to carbamazepine. He began treatment at 300 mg twice daily, and the dose was titrated to 600 mg twice daily. Over the following weeks, both he and his wife noted improved mood stability and a decrease in reactive anger. Stressors that once triggered rage were now more tolerable, and his emotional volatility diminished.

To support his efforts to reduce alcohol use, Mr D agreed to start naltrexone (50 mg/day) to reduce cravings. He appreciated the medication’s nonsedating profile and that it did not carry the same risks as traditional antidepressants. Over the next several weeks, he noticed fewer alcohol urges, improved control during social situations, and fewer episodes of impulsive drinking when distressed.

He also engaged in speech and language pathology for cognitive rehabilitation therapy that targeted persistent difficulties with attention and memory. Despite these gains, Mr D continued to struggle with symptoms consistent with TBI-related ADHD, particularly difficulty sustaining focus, disorganization, and emotional dysregulation. Recognizing the significant impact on his functional recovery and quality of life, the risks and benefits of a cautious stimulant trial were reviewed. Mr D agreed to try methylphenidate (20 mg/day), with close monitoring. Within 2 weeks, his concentration ability increased, he felt in greater control over his reactions, and his frustration tolerance improved.

His relationship with his wife also began to improve, and he successfully advocated to remain in his current job, showing initiative and insight into his progress. For the first time in years, Mr D described feeling hopeful—more in control of his emotions, his behavior, and his future.

CONCLUSION

Rage reactions can disrupt interpersonal relationships, work, academic activities, and happiness; in addition, they can be dangerous to those experiencing rage and to those around them. Rage, wrath, and fury are words used to describe the extreme end of irritability and anger that is often provoked by frustration and insults and that is manifest by aggressive behavior that appears reactive or lacking inhibition by cognitive processes. Rage is associated with conditions linked with low distress tolerance, increased impulsivity, or impaired cognition.

Rage is mediated by a distributed network that involves limbic structures (eg, the amygdala and ventromedial temporal cortex) for emotional arousal and appraisal and cortical regions (eg, the DLPFC, ACC, and DMN) for regulation and inhibition of aggressive responses. However, rage and impulsive aggression are also features of many mood disorders, personality disorders, and nonpsychiatric conditions. Although no medications have been approved by the FDA for anger or rage, many medications are used off-label for this purpose.

Article Information

Published Online: December 23, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04033

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: June 26, 2025; accepted August 26, 2025.

To Cite: Matta SE, DeSimone AC, Fisher DR, et al. Rage: differential diagnosis, evaluation, and management. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04033.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Matta, Stern); Department of Psychiatry, Bayhealth Medical Center, Dover, Delaware (DeSimone); Department of Psychiatry, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Dayton, Ohio (Weber); Department of Psychiatry, Lewis Gale Medical Center, Salem, Virginia (Braford); Malmstrom AFB, Great Falls, MT (Fisher); Wright Patterson AFB, Ohio (Weber). Matta, DeSimone, Fisher, Braford, Mastronardi, and Weber are co-first authors; Stern is the senior author.

Corresponding Author: Theodore A. Stern, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St, WRN 606, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Fisher is an active-duty Air Force officer and is employed by the US Department of Defense, but the opinions expressed in this article are his own and do not reflect those of the Uniformed Services University, the US Air Force, or the Department of Defense. Dr Weber is an active-duty Air Force officer and is employed by the US Department of Defense, but the opinions expressed in this article are his own and do not reflect those of the Uniformed Services University, the US Air Force, or the Department of Defense. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Matta, DeSimone, Braford, and Mastronardi report no disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Although there is no formal strategy for evaluating rage reactions, taking a thorough history that considers underlying neuropsychiatric conditions and comorbid conditions (eg, substance use) can assist in understanding rage reactions.

- The management of anger, aggression, and rage often involves the use of behavioral strategies, anxiety reduction techniques, and pharmacologic interventions.

- Cognitive-behavioral therapy helps individuals to understand the causes of their rage, to develop healthier thinking patterns, and to learn coping strategies to prevent outbursts. Dialectical behavioral therapy teaches individuals how to recognize, regulate, and respond to intense emotions (eg, anger and rage) and aggressive behaviors (eg, yelling, threatening others, being violent, and demonstrating hostility) in healthier ways. Mindfulness manages rage and anger by fostering awareness, acceptance, and a nonjudgmental attitude toward one’s emotions.

- Many rage management strategies focus on identifying anger, restructuring thoughts, modulating anger, and practicing alternative ways to manage strong emotions.

References (57)

- Homer. The Iliad. Fagles R, translator. New York, NY: Penguin Classics; 1990: Book 1, line 1.

- Leibenluft E, Stoddard J. The developmental psychopathology of irritability. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(4 Pt 2):1473–1487. PubMed CrossRef

- Waugh CE, Hamilton JP, Chen MC, et al. Neural temporal dynamics of stress in comorbid major depressive disorder and social anxiety disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;108:848–858.

- Spielberger CD, Reheiser EC, Sydeman SJ. Measuring the experience, expression, and control of anger. Issues Compr Pediatr Nurs. 1995;18(3):207–232–. PubMed CrossRef

- Gauthier KJ, Furr RM, Mathias CW, et al. Differentiating impulsive and premeditated aggression: self and informant perspectives among adolescents with personality pathology. J Pers Disord. 2009;23(1):76–84. PubMed CrossRef

- Copeland WE, Brotman MA, Costello EJ. Normative irritability in youth: developmental findings from the Great Smoky Mountains study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(8):635–642. PubMed CrossRef

- Moeller FG, Barratt ES, Dougherty DM, et al. Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(11):1783–1793. PubMed CrossRef

- State v. Leidholm, 334 N.W.2d 811 (N.D. 1983).

- State v. Kelly, 97 N.J. 178, 478 A.2d 364 (1984).

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association;2022:763-771.

- Klimecki OM, Sander D, Vuilleumier P. Distinct brain areas involved in anger versus punishment during social interactions. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10556. PubMed CrossRef

- Sorella S, Vellani V, Siugzdaite R, et al. Structural and functional brain networks of individual differences in trait anger and anger control: an unsupervised machine learning study. Eur J Neurosci. 2022;55(2):510–527. PubMed CrossRef

- Siever LJ. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(4):429–442. PubMed CrossRef

- Blair RJ. The neurobiology of psychopathic traits in youths. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(11):786–799. PubMed CrossRef

- Aymerich C, Bullock E, Rowe SMB, et al. Aggressive behavior in children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorder: a systematic review of the prevalence, associated factors, and treatment. JAACAP Open. 2025;3(1):42–55. PubMed CrossRef

- Lamsma J, Raine A, Kia SM, et al. Structural brain abnormalities and aggressive behaviour in schizophrenia: mega-analysis of data from 2095 patients and 2861 healthy controls via the ENIGMA consortium. medRxiv. 2024:2024.02.04.24302268.

- Tateno A, Jorge RE, Robinson RG. Clinical correlates of aggressive behavior after traumatic brain injury. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2003;15(2):155–160. PubMed CrossRef

- Ito M, Okazaki M, Takahashi S, et al. Subacute postictal aggression in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2007;10(4):611–614. PubMed CrossRef

- Saghir Z, Syeda JN, Muhammad AS, et al. The amygdala, sleep debt, sleep deprivation, and the emotion of anger: a possible connection? Cureus. 2018;10(7):e2912. PubMed CrossRef

- Bjureberg J, Gross JJ. Regulating road rage. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2021;15(3):e12586. PubMed CrossRef

- Shaffer RC, Reisinger DL, Schmitt LM, et al. Systematic review: emotion dysregulation in syndromic causes of intellectual and developmental disabilities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;62(5):518–557. PubMed CrossRef

- Witten JA, Coetzer R, Turnbull OH. Shades of rage: applying the process model of emotion regulation to managing anger after brain injury. Front Psychol. 2022;13:834314. PubMed CrossRef

- Miles SR, Hammond FM, Neumann D, et al. Evolution of irritability, anger, and aggression after traumatic brain injury: identifying and predicting subgroups. J Neurotrauma. 2021;38(13):1827–1833. PubMed CrossRef

- Wang Y, Qu W, Ge Y, et al. Effect of personality traits on driving style: psychometric adaption of the multidimensional driving style inventory in a Chinese sample. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0202126. PubMed CrossRef

- Ahmed AO, Green BA, McCloskey MS, et al. Latent structure of intermittent explosive disorder in an epidemiological sample. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(10):663–672. PubMed CrossRef

- Laitano HV, Ely A, Sordi AO, et al. Anger and substance abuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz J Psychiatry. 2022;44(1):103–110. PubMed CrossRef

- Alia-Klein N, Gan G, Gilam G, et al. The feeling of anger: from brain networks to linguistic expressions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;108:480–497. PubMed CrossRef

- Van Kleef GA, Van Dijk E, Steinel W, et al. Anger in social conflict: cross-situational comparisons and suggestions for the future. Group Decis Negot. 2008;17(1):13–30. CrossRef

- Fabiansson EC, Denson TF. The effects of intrapersonal anger and its regulation in economic bargaining. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51595. PubMed CrossRef

- Schat A, Frone MR. Exposure to psychological aggression at work and job performance: the mediating role of job attitudes and personal health. Work Stress. 2011;25(1):23–40. PubMed CrossRef

- Valiente C, Swanson J, Eisenberg N. Linking students’ emotions and academic achievement: when and why emotions matter. Child Dev Perspect. 2012;6(2):129–135. PubMed CrossRef

- Vuoksimaa E, Rose RJ, Pulkkinen L, et al. Higher aggression is related to poorer academic performance in compulsory education. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62(3):327–338. PubMed CrossRef

- Gilam G, Maron-Katz A, Kliper E, et al. Tracing the neural carryover effects of interpersonal anger on resting-state fMRI in men and their relation to traumatic stress symptoms in a subsample of soldiers. Front Behav Neurosci. 2017;11:252. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee AH, DiGiuseppe R. Anger and aggression treatments: a review of meta-analyses. Curr Opin Psychol. 2018;19:65–74 PubMed CrossRef

- Frazier SN, Vela J. Dialectical behavior therapy for the treatment of anger and aggressive behavior: a review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19(2):156–163. CrossRef

- Ciesinski NK, Sorgi-Wilson KM, Cheung JC, et al. The effect of dialectical behavior therapy on anger and aggressive behavior: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2022;154:104122. PubMed CrossRef

- Singh MK, Hu R, Miklowitz DJ. Preventing irritability and temper outbursts in youth by building resilience. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2021;30(3):595–610. PubMed CrossRef

- Byrne G, Cullen C. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for anger, irritability, and aggression in children, adolescents, and young adults: a systematic review of intervention studies. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25(2):935–946. PubMed CrossRef

- Zarling A, Lawrence E, Marchman J. A randomized controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy for aggressive behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):199–212. PubMed CrossRef

- Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 1: psychostimulants, alpha-2 agonists, and atomoxetine. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):42–51. PubMed CrossRef

- Kazdin AE. Problem-solving skills training and parent management training for oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. In: Weisz JR, Kazdin AE, eds. Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents. 2nd ed.. The Guilford Press;2010:211–226.

- Felthous AR, Stanford MS. A proposed algorithm for the pharmacotherapy of impulsive aggression. J Am Acad Psychiatry L. 2015;43(4):456–467. PubMed

- Felthous AR, McCoy B, Nassif JB, et al. Pharmacotherapy of primary impulsive aggression in violent criminal offenders. Front Psychol. 2021;12:744061. PubMed CrossRef

- Prado-Lima PA. Tratamento farmacológico da impulsividade e do comportamento agressivo [Pharmacological treatment of impulsivity and aggressive behavior]. Braz J Psychiatry. 2009;31(suppl 2):S58–S65. PubMed CrossRef

- Chen A, Copeli F, Metzger E, et al. The psychopharmacology algorithm project at the Harvard South Shore program: an update on management of behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113641. PubMed CrossRef

- London EB, Zimmerman-Bier BL, Yoo JH, et al. High-dose propranolol for severe and chronic aggression in autism spectrum disorder: a pilot, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized crossover study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024;44(5):462–467. PubMed CrossRef

- Pringsheim T, Hirsch L, Gardner D, et al. The pharmacological management of oppositional behaviour, conduct problems, and aggression in children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Part 2: antipsychotics and traditional mood stabilizers. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(2):52–61. PubMed CrossRef

- van Schalkwyk GI, Beyer C, Johnson J, et al. Antipsychotics for aggression in adults: a meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;81:452–458. PubMed CrossRef

- Fusaroli M, Raschi E, Giunchi V, et al. Impulse control disorders by dopamine partial agonists: a pharmacovigilance-pharmacodynamic assessment through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25(9):727–736. PubMed CrossRef

- Marchi M, Grenzi P, Boks MP. Clonidine for post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review of the current evidence. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2024;15(1):2366049. PubMed CrossRef

- Connor DF, Glatt SJ, Lopez ID, et al. Psychopharmacology and aggression. I: a meta-analysis of stimulant effects on overt/covert aggression-related behaviors in ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(3):253–261. PubMed CrossRef

- Reyes VA, Hicklin TA. Anger in the combat zone. Mil Med. 2005 Jun;170(6):483–487. PubMed CrossRef

- Cooper DC, Campbell MS, Baisley M, et al. Combat and operational stress programs and interventions: a scoping review using a tiered prevention framework. Mil Psychol. 2024;36(3):253–265. PubMed CrossRef

- Goldberg SB, Riordan KM, Sun S, et al. Efficacy and acceptability of mindfulness-based interventions for military veterans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2020;138:110232. PubMed CrossRef

- Allison TL, Curry RR. Introduction: invitation to rage. In: Stages of Rage: Emotional Eruption, Violence, and Social Change. New York University Press; 1996.

- Crain JC. Teaching Stephen King: horror, the supernatural, and new approaches to literature. Alissa Burger Palgrave Macmillan. 2016;40(4):427–428.

- Mapping contemporary cinema. Available from: https://mcc.sllf.qmul.ac.uk/?p=747 Accessed June 25, 2025.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!