Initially described by Jules Cotard in 1880, Cotard’s syndrome is a rare neuropsychiatric manifestation marked by nihilistic delusions involving beliefs that one is dead or missing organs.1 It is not a formal diagnosis in widely used diagnostic classification systems (eg, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition [DSM-5-TR] or International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision). Instead, Cotard’s syndrome is mainly used in the literature to describe unique nihilistic delusions associated with underlying mood, psychotic, and neurological disorders.2–5 As the pathophysiology of Cotard’s syndrome remains unclear, treatment is typically guided by the underlying disorder, often including antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, or electroconvulsive therapy to manage symptoms or an underlying psychiatric disorder.4,5

Case Report

We report the case of a 42-year-old woman with schizophrenia and multiple prior hospitalizations who presented with worsening psychosis and physical aggression toward her mother. The altercation stemmed from delusions that her parents had “shocked” her while she was sleeping and removed her brain, lungs, and colon and then sold them. She noted the absence of scars by explaining that the incisions were “rolled” shut. She questioned how she was still alive. She believed that buyers had consumed her organs and that her neighbors were also part of the broader conspiracy. Review of the patient’s medical records showed that she was admitted 10 months prior for delusions of her mother trying to take her “heart out” and her father replacing her lungs with “bad lungs.” She was treated with aripiprazole and discharged after 10 days with symptom improvement.

During the current evaluation, she was pleasant and cooperative. She reported hearing voices throughout the day from “friends on the internet,” despite having no internet access. The voices told her that her parents were responsible. She acknowledged that her beliefs did not make sense and lacked evidence, but said she trusted the voices, believing they had no reason to lie to her, even though she admitted she did not know who they were. Her presentation was notable for elaborate delusions, auditory hallucinations, poor insight, and intact orientation and memory. She endorsed anxiety and having a depressed mood recently, expressing that she felt sad and hopeless due to the situation. She denied visual hallucinations, suicidal ideation, and homicidal ideation, although she expressed anger toward the perceived perpetrators. Physical and neurological examinations were normal. She and her mother confirmed adherence to haloperidol and aripiprazole. Her differential diagnosis included schizoaffective disorder and depression with psychotic features. However, both were ruled out after determining that her mood episodes were present only a small amount of time during her illness. She met DSM-5-TR criteria for schizophrenia, and her delusional symptoms were consistent with published literature describing Cotard’s syndrome.

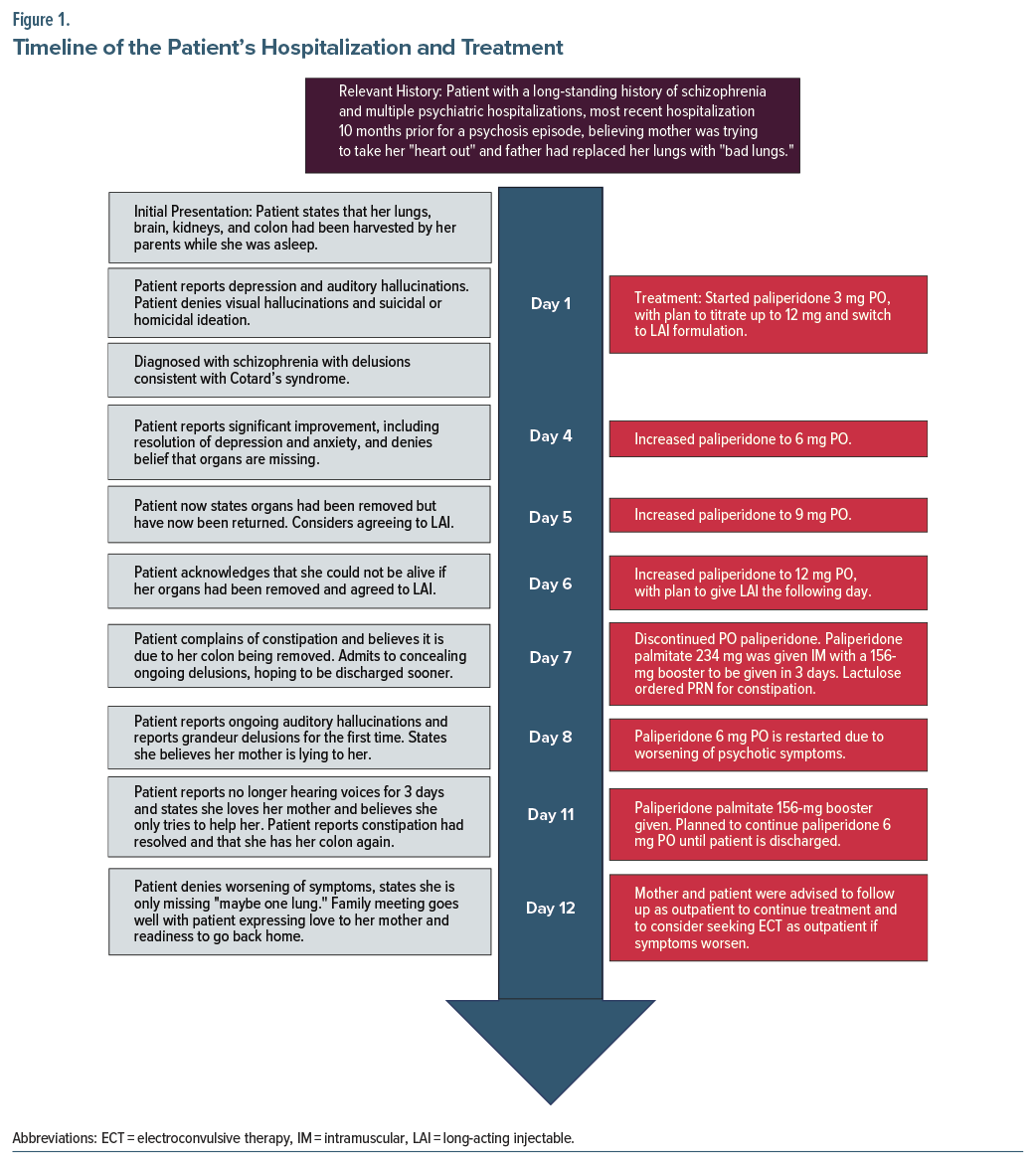

Oral paliperidone was initiated at 3 mg daily, with plans to titrate to 12 mg and transition to the long-acting injectable (LAI) formulation. On day 4, the dosage was increased to 6 mg. She denied still believing her organs were missing and reported resolution of her mood symptoms. The next day, her dose was increased to 9 mg, and she now felt her organs had been removed but were returned to her body. On day 6, the dose was titrated to 12 mg. The patient showed improved reality testing, acknowledging she “wouldn’t be alive” if her organs had truly been removed.

However, on day 7, the patient complained of new-onset constipation, citing it as proof she no longer had a colon and that her mother had been lying, and admitted to previously concealing her delusions to appear stable enough to be discharged sooner. She also revealed new grandiose and persecutory delusions, claiming to be worth “trillions” and that banks were conspiring to withhold it from her. Lactulose was ordered as needed for the patient’s constipation, and with the patient’s consent, LAI paliperidone palmitate 234 mg was administered. The following day, oral paliperidone 6 mg was added to her treatment due to continued psychotic symptoms.

On day 11, she received a 156-mg LAI paliperidone palmitate booster. Following resolution of her constipation, she concluded that she had a colon again and believed most of her organs had been “returned.” Also, her relationship with her mother had normalized, as she expressed love for her mother and appreciation for her care. At discharge, she had denied auditory hallucinations for 4 days, although she still wondered if one lung was missing. She was deemed to pose no risk to herself or others and demonstrated improved insight. The mother was advised to ensure outpatient follow-up to continue treatment and to consider seeking electroconvulsive therapy if the patient’s symptoms worsen, although this was not available at our facility. Figure 1 provides a timeline of the patient’s hospitalization and treatment.

Discussion

This case illustrates several key clinical principles in managing Cotard’s syndrome within the context of schizophrenia. A particularly notable feature was the role of auditory hallucinations in the form of “friends on the internet,” reinforcing the delusions of organ removal. Another unique feature of this case was how the somatic symptom of constipation reinforced delusions of colon removal. Additionally, this case demonstrated that treating the underlying schizophrenia may reduce nihilistic delusions.

During treatment planning for this patient, LAI paliperidone was selected as the best option because the patient had refractory symptoms while compliant with haloperidol and aripiprazole but was naive to paliperidone. Given its long half-life and favorable side effect profile, it was chosen over other options discussed, including olanzapine, clozapine, and risperidone.

Overall, this case adds to the limited literature on Cotard’s syndrome as a rare presentation within schizophrenia, highlighting the diverse ways psychotic symptoms can appear, and that in patients with antipsychotic refractory symptoms, switching to an antipsychotic that a patient has not tried previously may be an effective treatment option within an overall treatment plan. Cotard’s syndrome remains a rare and complex manifestation of severe psychiatric illness. This case highlights how individualized antipsychotic treatment and somatic symptom management can lead to meaningful improvement. Recognition and diagnosis of Cotard’s syndrome within schizophrenia can inform effective interventions and improve outcomes.

Article Information

Published Online: January 8, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr04044

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25cr04044

Submitted: July 15, 2025; accepted September 25, 2025.

To Cite: Rosenfeld M, Aslam H, Memon RI. Somatic delusions in schizophrenia: a case of Cotard syndrome. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25cr04044.

Author Affiliations: Sam Houston State University, College of Osteopathic Medicine, Conroe, Texas (Rosenfeld); Psychiatry Residency Program, Baptist Hospitals of Southeast Texas, Beaumont, Texas (Aslam, Memon).

Corresponding Author: Mark Rosenfeld, BA, Sam Houston State University, College of Osteopathic Medicine, 925 City Central Ave, Conroe, Texas 77304 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Consent was received from the patient to publish the case report, and information, including dates, has been de-identified to protect anonymity.

References (5)

- Berrios GE, Luque R. Cotard’s delusion or syndrome?: a conceptual history. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36(3):218–223. PubMed CrossRef

- Sahoo A, Josephs KA. A neuropsychiatric analysis of the cotard delusion. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2018;30(1):58–65. PubMed CrossRef

- Taib NIA, Wahab S, Khoo CS, et al. Case report: cotard’s syndrome in anti-N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor (Anti-NMDAR) encephalitis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:779520. PubMed CrossRef

- Saxena M, Sapkale B, Varma S, et al. Unlocking the enigma of cotard’s syndrome: a narrative review of its clinical manifestations and therapeutic strategies. J Clin Diagn Res. 2024;18(7):VE01–VE03.

- Kobayashi T, Inoue K, Shioda K, et al. Effectiveness of electroconvulsive therapy for depression and cotard’s syndrome in a patient with frontotemporal lobe dementia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:627460. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!