Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04012

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you been uncertain about what to tell your patients about using or discontinuing substances during pregnancy? Have you avoided asking questions of or making recommendations to your patients regarding substance use during pregnancy for fear that you would offend them? Have you wished that you had more information about the risks of smoking cigarettes and using drugs during pregnancy and the postpartum period? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Ms A, a 33-year-old G3P1011 with a history of hyperthyroidism and generalized anxiety disorder, presented to our obstetric (OB) triage unit at 28 weeks and 2 days. On paper, her pregnancy was uncomplicated. Ms A established prenatal care in the first trimester, had serial thyroid hormone levels during the pregnancy showing well-controlled hyperthyroidism, and had a reassuring gestational diabetes screen the week prior to her presentation. Her genetic screening and a recent fetal anatomic survey reflected a normally developing XX fetus. For Ms A and her supportive partner, this pregnancy was going as smoothly as they could have hoped for, except for one thing. She was drinking a bottle and a half of wine daily.

Screening in the first trimester through the widely adopted “5P’s” screening tool was negative. This screening tool for substance use and substance use disorders (SUDs) in pregnancy—which inquires about use during the current pregnancy, past use, parental use, partner use, and peer use—is one of several used across the United States.1,2 The screen was administered by the medical assistant at her initial prenatal visit. Ms A did not disclose any concerning exposures at that time, and her obstetrician’s subjective gestalt deemed Ms A low risk.

However, when she arrived to OB triage that day, she explained that drinking wine had become a way to deal with the stresses of raising her 2-year-old toddler while working 70 hours each week as an investment banker. “Things will settle down once I am pregnant,” she had reassured herself as she and her partner were trying to conceive. After her 13-week nuchal translucency ultrasound, it became clear that her plan to taper alcohol intake was not working. She noted strong cravings and withdrawal symptoms after brief periods of abstinence. Despite these symptoms that were indicative of physiologic dependence to alcohol, Ms A said she felt intensely ashamed about being unable to stop drinking. She feared that seeking help would lead to being viewed as an unfit mother and possible loss of custody of her infant. Meanwhile, reassurance about her pregnancy during prenatal visits up until that time that “everything was going well” contributed to her denial and towards isolation and secrecy. Those who knew about her pregnancy were unaware of her drinking. Those who knew about her excessive alcohol consumption were in the dark when it came to her pregnancy.

Now at 28 weeks, secrecy was no longer a viable option. She told her partner and her obstetrician about her alcohol intake. This prompted her to present to our triage unit on a Saturday afternoon for medically supervised withdrawal or “detox.” Ms A was admitted to our high-risk antepartum service and treated with a Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment–driven benzodiazepine protocol. Per institutional policy, a written consent was signed, which permitted collection of maternal samples for toxicology testing to guide clinical management. With her partner at her bedside, Ms A was visited by various specialists to ensure wrap-around care.

She was counseled jointly by addiction and maternal-fetal medicine specialists, and the pharmacotherapeutic options for alcohol use disorder (AUD) in pregnancy were reviewed (including use of naltrexone/Vivitrol, gabapentin, and acamprosate). Community resources were explored, and Ms A was introduced to a peer-recovery coach during her hospitalization. Ms A was torn between the promise of being on the path to recovery and the multitude of uncertainties that awaited her. The range of phenotypes seen in fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASDs), coupled with the inability to accurately test prenatally for this condition, was unsettling. Moreover, the requirements for involving the Department of Children and Families (DCF), the child welfare agency in our state, were not clear to her.

After reviewing the risks and benefits of pharmacologic interventions, Ms A was started on oral naltrexone and gabapentin for her AUD, along with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor for her worsening depression and anxiety. Her stated goal was abstinence from alcohol. She was referred for weekly visits with an addiction-trained psychiatrist and therapist. A plan for fetal testing was outlined, and referrals were provided to facilitate meeting with our neonatology and high-risk anesthesia teams.

DISCUSSION

How Often Do Women Use Alcohol, Tobacco, and Other Substances During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period?

About half of the women who use tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana continue to do so (although often at a reduced frequency) after learning of their pregnancy,3 which roughly mirrors the proportion of pregnancies that are unintended. National household surveys estimate rates of use during pregnancy to be 15% for alcohol, 5% for tobacco, 5% for marijuana, and 5% for opioids.4–6 While substance use during pregnancy is a leading modifiable risk factor for poor maternal and child outcomes, it is under-recognized by clinicians due to stigma and is the subject of punitive policies that reflect this stigma.4,7

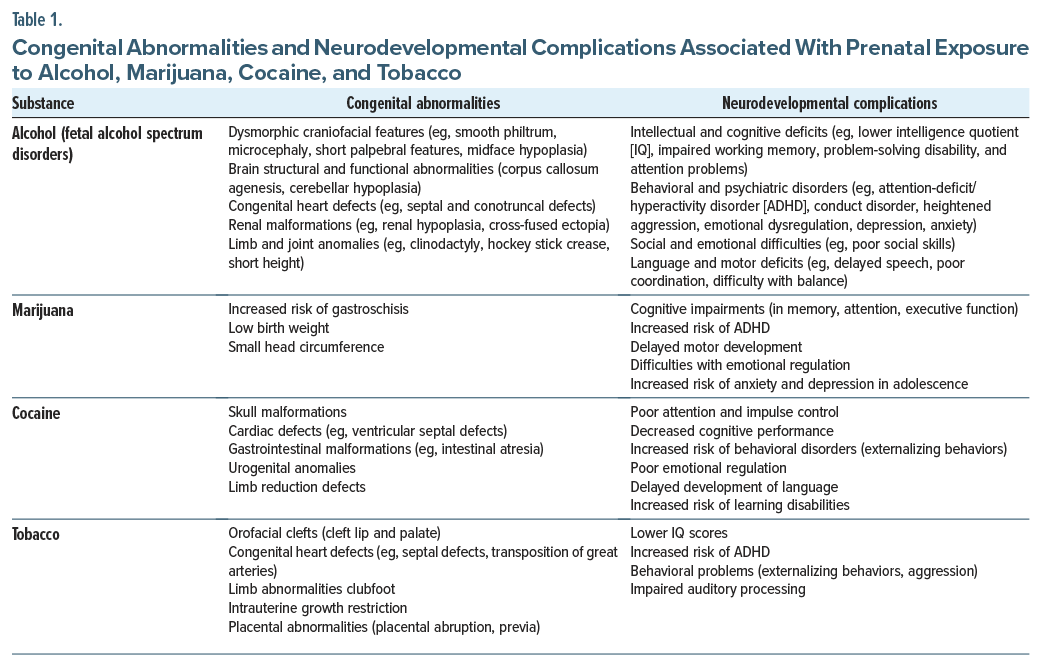

Which Congenital Abnormalities and Neurodevelopmental Complications Have Been Associated With Use of Alcohol, Marijuana, Cocaine, and Tobacco During Pregnancy?

Congenital abnormalities and neurodevelopmental complications associated with use of alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and tobacco during pregnancy are shown in Table 1. FASDs describe a continuum of structural, cognitive, and behavioral deficits8,9 as well as distinct craniofacial anomalies, including a thin upper lip, smooth philtrum, and small eyes, along with varying degrees of intellectual disabilities and behavioral dysregulation.10 Beyond these hallmark features, prenatal alcohol exposure can disrupt fetal brain development, which contributes to cognitive deficits and emotional dysregulation. These neurodevelopmental complications have been associated with increasing rates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), social isolation, and learning disabilities, which can persist into adulthood.11 In addition to neurological and behavioral sequelae, prenatal alcohol exposure has been linked to congenital cardiac, renal, and skeletal system abnormalities, further contributing to long-term morbidity.12 Importantly, manifestations of FASD can arise at any stage of childhood and persist throughout life, underscoring the need for early identification and intervention to mitigate adverse outcomes.

While prenatal exposure to cannabis has been viewed as being safe in pregnancy, it has been associated with low birth weight, preterm birth, and intrauterine growth restriction in offspring.13,14 The main active compound in marijuana, δ-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), readily crosses the placenta and directly affects fetal brain development. THC interacts with the endocannabinoid system, which plays a critical role in neurogenesis, neuronal differentiation, and synaptic plasticity. Disruptions in these neurobiological processes during critical phases of brain development may contribute to long-term cognitive and behavioral impairments.15 Furthermore, children who have been exposed to marijuana in utero are more likely to develop mental health disorders and externalizing behaviors (eg, hyperactivity and impulsivity).16,17

Prenatal exposure to cocaine has been linked with intrauterine growth restriction, preterm births, and an increased risk of a neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), which can result in withdrawal symptoms (eg, irritability, feeding difficulties, and respiratory distress in offspring).18 The detrimental effects of prenatal cocaine exposure are largely attributed to its vasoconstrictive properties, which impair placental blood flow and reduce the delivery of oxygen and nutrients to the fetus. This placental insufficiency can lead to fetal hypoxia and restricted growth, which increases the risk of being born with a low birth weight and manifesting developmental delays. In addition, cocaine exposure disrupts fetal neurotransmitter systems, particularly dopamine and serotonin pathways, which are crucial for normal brain development.19 Moreover, prospective epidemiologic studies suggest that cocaine consumption during pregnancy can lead to a heightened risk for cognitive and behavioral difficulties.18,20 Maternal smoking during pregnancy is a well-established risk factor for low birth weight, preterm birth, and respiratory complications in infants.21,22 Nicotine, the psychoactive compound inhaled from tobacco smoking, electronic nicotine delivery systems (ie, vaping), or via buccal mucosae, and various nicotine replacement therapies constrict uterine and placental vasculature, thereby reducing oxygen and the nutrient supply to the fetus. Prenatal tobacco exposure has also been associated with congenital anomalies (eg, cleft lip and palate), highlighting the potential teratogenic effects of the hundreds of compounds released from the combustion of tobacco.21 In addition to physical defects, accumulating evidence suggests that in utero exposure to tobacco smoke may disrupt neural pathways that are critical for regulation of cognition and behavior. For example, children born to mothers who smoked tobacco during pregnancy have a higher incidence of ADHD, learning disabilities, and other neurobehavioral disorders,23,24 although underlying mechanisms are not well elucidated.25,26 The nature and severity of neurodevelopmental complications associated with intrauterine exposure to commonly used licit and illicit drugs in epidemiologic studies are shown in Table 2.

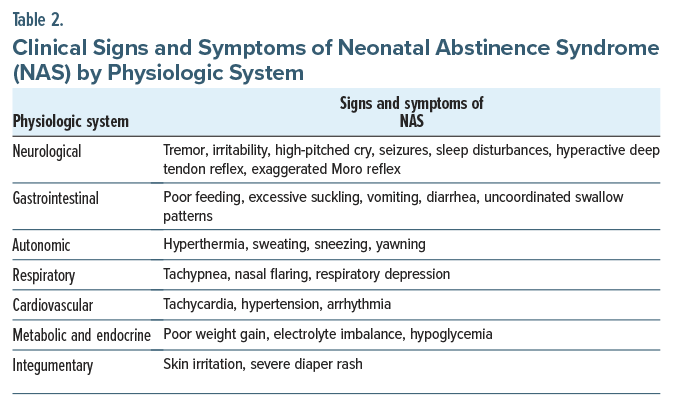

What Are the Manifestations of Drug Withdrawal in Newborns at Delivery?

NAS refers to signs and symptoms in the newborn attributed to the cessation of prenatal exposure (via placental transfer) to a wide variety of licit and illicit substances including prescribed medications.27 Common neurological signs include tremor, irritability, and high pitched crying.28 Signs of NAS can emerge shortly after birth, with their severity influenced by the type of drug used, the timing of the mother’s last use during pregnancy, and whether the baby is full term or premature. For instance, withdrawal from opioids and alcohol typically begins within 24 to 72 hours after delivery. Without appropriate management, withdrawal symptoms can interfere with the newborn’s healthy development and often necessitates medical interventions (eg, pharmacologic treatment or supportive care).

A subset of NAS, neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), describes the specific signs and symptoms attributed to the abrupt discontinuation of opioid agonists (including medications used to treat opioid use disorder) in the fetal circulation upon delivery. Despite known risks associated with NOWS, abrupt discontinuation of opioids before delivery in physiologically dependent pregnant patients is contraindicated. Increased oxygen demands associated with acute opioid withdrawal reduces available oxygenated blood to the placental and fetal circulation, which risks fetal distress or even demise.29

Why Might Nicotine Replacement Therapy Be Safer Than Cigarette Smoking or Vaping?

While behavioral support is the first-line treatment for smoking cessation during pregnancy, medications may also be necessary.30 Although current data have not yet documented the effectiveness of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) during pregnancy, some randomized controlled studies have shown that NRT is superior to nontreatment or to behavioral support alone in supporting smoking cessation in pregnant patients.31 Success rates may be even higher when using a higher dose of NRT, because pregnancy increases the metabolism of nicotine.32 Although NRT exposes the fetus to nicotine, NRT avoids fetal exposure to tobacco smoke and other toxins found in cigarettes that are known teratogens, thereby contributing to its safety when compared to cigarette smoking.33 For the same reason, NRT is preferred to use of electronic cigarettes (vaping). Electronic cigarettes aerosolize additives that are created by heating propylene glycol and vegetable glycerol; unfortunately, the safety of fetal exposure to these additional components has not been well studied.34

In addition, NRT exposes the mother to continuous low doses of nicotine, rather than the acute nicotine spikes seen during cigarette smoking, which makes it theoretically safer to the fetus given that concentrations of nicotine are higher in the fetal serum than in the maternal serum.35 Despite animal studies that have raised concern regarding the risks to a fetus with nicotine exposure, human studies have not identified any consistent association between NRT during pregnancy and adverse fetal or pregnancy outcomes. Therefore, experts typically counsel pregnant patients to use NRT only when they are committed to smoking cessation and after a thorough discussion of the risks and benefits.

When, Where, and To Whom Must Clinicians Report Maternal Use of Substances During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period?

Under the federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, state governments are required to have policies and procedures in place about mandated reporting to local authorities of pregnant patients who use substances. These policies, that vary by state, may be broadly divided into the 14 jurisdictions that explicitly define prenatal substance use as an act of child abuse or neglect that requires mandated reporting by health care providers to child protective authorities and states that leave the decision to report to the discretion of providers based on the extent to which parental substance use is expected to endanger the well-being of the infant after delivery.36,37 Such mandates have been the subject of intense controversy.38

The prevailing view of substance use during pregnancy as a form of child abuse and neglect not only diverges notably from the modern disease model of addiction that favors treatment over punitive action but dissuades expectant parents from seeking prenatal care,39 treatment for addiction,40 and participation in developmental research aimed at informing intervention and prevention strategies.7 Furthermore, the criminalization of substance use by pregnant women has been applied disproportionately in ways that magnify systemic racial inequities.41 Pregnancy is associated with a more robust protective effect on the risk of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug abuse than any known intervention.42–44 In the absence of substance abuse treatment programs designed to meet the needs of new mothers of infants via the provision of childcare and parenting training and supervision, criminalization ironically removes the most salient motivation for recovery for many parents.45

How Can Clinicians Communicate Effectively With Their Patients (and their partners) About the Hazards of Drug Use and Abuse?

Unfortunately, the causal effects of prenatal exposure on offspring outcomes are not well-established. With the exception of alcohol, a known teratogen, the extent to which prenatal exposures directly influence fetal brain development, are markers for familial and social processes that covary with exposure, or are some combination is an intense area of ongoing inquiry.26,33,46 Within-family and prospective cohort studies of children parentally exposed to tobacco and other drugs support the confounding of exposure-outcome associations by familial influences.47 The myriad demographic, genetic, and phenotypic characteristics associated with substance use during pregnancy influence neurodevelopment directly and indirectly via interactions with environmental factors.25,48–50 Gestational and fetal characteristics51; the timing, frequency, dosage, and patterns of use52; and conditions in the postnatal environment are further implicated in neurodevelopmental outcomes associated with prenatal exposures.53

Within this context, emphasis in primary care settings should be on screening, identification, brief intervention, and referral to treatment, as appropriate, for pregnant and nonpregnant patients. While some providers are hesitant to address potentially stigmatizing topics (eg, substance use) with patients, there is strong evidence for the efficacy and acceptability of such care in primary care settings.54,55 Beyond minimizing blame, the emphasis on support for behavioral change and treatment, when indicated, not only removes unhelpful blame and shame but also addresses the most salient modifiable influences on familial well-being once exposure has occurred.

SUDs are highly comorbid with mood and anxiety disorders in both sexes,56 and the persistent use of substances after pregnancy is strongly associated with psychiatric symptoms.57 Therefore, screening for psychiatric conditions and referral for specialized care, when appropriate, are critical to the optimization of maternal and child health.

What Happened to Ms A?

Ms A returned to the labor and delivery suite for a scheduled induction at 39 weeks. The OB nurse involved in her care at 28 weeks was present for the uncomplicated vaginal delivery of Ms A’s vigorous baby girl (who had Apgar scores of 9 and 10). Although her 11 weeks in recovery had been a winding road filled with moments of optimism, occasional lapses to alcohol use, and worries about what to expect in the postpartum period, Ms A continued to use her medications for AUD and had frequent follow-up visits scheduled for her high risk postpartum period. Ultimately, with an informal plan of safe care in place, opening a case file with DCF was deemed unnecessary, as it was not in the family’s best interest.

Ms A’s courage to present for care at 28 weeks was her first step toward recovery. Ms A (a white, partnered woman with financial and social assets) sought help at 28 weeks, and her plea was answered. For many pregnant women, requests for help during pregnancy go unanswered and worse, lead to parental punishment.

CONCLUSION

Unfortunately, a myriad of demographic, genetic, and phenotypic characteristics associated with substance use during pregnancy influences neurodevelopment directly and indirectly via interactions with environmental factors. Moreover, while substance use during pregnancy is a leading modifiable risk factor for poor maternal and child outcomes, it is under-recognized by clinicians due to stigma and becomes the target of punitive policies that reflect this stigma.

Roughly half of infants who have been exposed to alcohol or other substances during their fetal development are delivered prematurely. While the exact mechanisms are unclear, ongoing use of many substances during pregnancy has been linked to adverse neurodevelopmental and cardiometabolic outcomes across the lifespan. The prevalence of intrauterine exposure to addictive substances is probably underestimated due to stigma, misperceptions (by patients and clinicians alike), and the criminalization of SUDs in pregnant women.

The prevailing view of substance use during pregnancy as a form of child abuse and neglect diverges from the modern disease model of addiction (that favors treatment over punishment) and dissuades expectant parents from seeking prenatal care, treatment for addiction, and participation in developmental research aimed at informing intervention and prevention strategies. Thus, consistent and compassionate conversations with patients facilitate the prevention of adverse sequelae.

Article Information

Published Online: November 11, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04012

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: May 27, 2025; accepted July 29, 2025.

To Cite: Hogan CS, Vyas CM, Woods GT, et al. Talking to your patients about alcohol, marijuana, and substance use during pregnancy. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04012.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital/ Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Hogan, Vyas, Massey, Stern); Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Woods).

Corresponding Author: Theodore A. Stern, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St, WRN 606, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]). Hogan, Vyas, and Woods are co-first authors; Massey and Stern are co-senior authors.

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Vyas has received research support from the Alzheimer’s Association, Mars Edge, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention and honoraria from Haleon and Harvard Medical School. Dr Massey receives funding from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01DA05070. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Hogan and Woods report no relevant financial relationships.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Signs of neonatal abstinence syndrome can emerge shortly after birth, with their severity influenced by the type of drug used, the timing of the mother’s last use during pregnancy, and whether the baby is full term or premature.

- While behavioral support is the first-line treatment for smoking cessation during pregnancy, some randomized controlled studies have shown that nicotine replacement therapy is superior to nontreatment or to behavioral support alone in supporting smoking cessation in pregnant patients.

- Under the federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act, state governments are required to have policies and procedures in place regarding mandated reporting to local authorities of pregnant patients who use substances.

References (57)

- Ondersma SJ, Chang G, Blake-Lamb T, et al. Accuracy of five self-report screening instruments for substance use in pregnancy. Addiction. 2019;114(9):1683–1693. PubMed CrossRef

- Coleman-Cowger VH, Oga EA, Peters EN, et al. Accuracy of three screening tools for prenatal substance use. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;133:952–961. PubMed CrossRef

- Thompson R, DeJong K, Lo J. Marijuana use in pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2019;74(7):415–428. PMCID:PMC7090387. PubMed CrossRef

- Chang G. Maternal substance use: consequences, identification, and interventions. Alcohol Res. 2020;40(2):06. PubMed CrossRef

- Denny CH, Acero CS, Naimi TS, et al. Consumption of alcohol beverages and binge drinking among pregnant women aged 18–44 years—United States, 2015–2017. MMWR. 2019;68(16):365–368. PubMed CrossRef

- Zipursky J, Juurlink DN. Opioid use in pregnancy: an emerging health crisis. Obstet Med. 2021;14(4):211–219. PubMed CrossRef

- Shah SK, Perez-Cardona L, Helner K, et al. How penalizing substance use in pregnancy affects treatment and research: a qualitative examination of researchers’ perspectives. J L Biosci. 2023;10(2):lsad019. PubMed CrossRef

- Lee K-N, Kim HJ, Choe K, et al. Effects of fetal images produced in virtual reality on maternal-fetal attachment: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25(1):e43634. PubMed CrossRef

- DHHS DoHaHS. Alcohol’s Effects on Health. Research-Based Information on Drinking and its Impact: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse. Accessed February 18, 2025

- Mattson SN, Bernes GA, Doyle LR. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: a review of the neurobehavioral deficits associated with prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019;43(6):1046-1062. PubMed CrossRef

- Landgren V, Svensson L, Gyllencreutz E, et al. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders from childhood to adulthood: a Swedish population-based naturalistic cohort study of adoptees from Eastern Europe. BMJ open. 2019;9(10):e032407. PubMed CrossRef

- DeJong K, Olyaei A, Lo JO. Alcohol use in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2019;62(1):142–155. PubMed CrossRef

- Avalos LA, Oberman N, Alexeeff SE, et al. Early maternal prenatal cannabis use and child developmental delays. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(10):e2440295. PubMed CrossRef

- Chang JC, Tarr JA, Holland CL, et al. Beliefs and attitudes regarding prenatal marijuana use: perspectives of pregnant women who report use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;196:14–20. PubMed CrossRef

- Bara A, Ferland J-MN, Rompala G, et al. Cannabis and synaptic reprogramming of the developing brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2021;22(7):423–438. PubMed CrossRef

- Roncero C, Valriberas-Herrero I, Mezzatesta-Gava M, et al. Cannabis use during pregnancy and its relationship with fetal developmental outcomes and psychiatric disorders. A systematic review. Reprod Health. 2020;17:25–29. PubMed CrossRef

- Ikeda AS, Knopik VS, Bidwell LC, et al. A review of associations between externalizing behaviors and prenatal cannabis exposure: limitations and future directions. Toxics. 2022;10(1):17. PubMed CrossRef

- Ross EJ, Graham DL, Money KM, et al. Developmental consequences of fetal exposure to drugs: what we know and what we still must learn. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(1):61–87. PubMed CrossRef

- Martin MM, Graham DL, McCarthy DM, et al. Cocaine-induced neurodevelopmental deficits and underlying mechanisms. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2016;108(2):147–173. PubMed CrossRef

- Singer LT, Arendt R, Minnes S, et al. Cognitive and motor outcomes of cocaine exposed infants. JAMA. 2002;287(15):1952–1960. PubMed CrossRef

- Cornelius MD, Day NL. Developmental consequences of prenatal tobacco exposure. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22(2):121–125. PubMed CrossRef

- Sequí-Canet JM, Sequí-Sabater JM, Marco-Sabater A, et al. Maternal factors associated with smoking during gestation and consequences in newborns: results of an 18-year study. J Clin Translational Res. 2022;8(1):6.

- Chen VC-H, Lee CT-C, Wu S-I, et al. Neurobehavioral disorders among children born to mothers exposed to illicit substances during pregnancy. BMC Med. 2024;22(1):581. PubMed CrossRef

- Gustavson K, Ystrom E, Stoltenberg C, et al. Smoking in pregnancy and child ADHD. Pediatrics. 2017;139(2):e20162509. PubMed CrossRef

- Estabrook R, Massey SH, Clark CA, et al. Separating family-level and direct exposure effects of smoking during pregnancy on offspring externalizing symptoms: bridging the behavior genetic and behavior teratologic divide. Behav Genet. 2016;46(3):389–402. PubMed CrossRef

- Knopik VS. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child outcomes: real or spurious effect? Dev Neuropsychol. 2009;34(1):1–36. PubMed CrossRef

- Coyle MG, Brogly SB, Ahmed MS, et al. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):47. PubMed CrossRef

- Anbalagan S, Falkowitz DM, Mendez MD. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. StatPearls [internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Esposito DB, Huybrechts KF, Werler MM, et al. Characteristics of prescription opioid analgesics in pregnancy and risk of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome in newborns. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2228588. PubMed CrossRef

- Tran DT, Cohen JM, Donald S, et al. Risk of major congenital malformations following prenatal exposure to smoking cessation medicines. JAMA Intern Med. 2025;185(6):656–667. PubMed CrossRef

- Claire R, Chamberlain C, Davey MA, et al. Pharmacological interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3(3). PubMed CrossRef

- Bowker K, Lewis S, Coleman T, et al. Changes in the rate of nicotine metabolism across pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Addiction. 2015;110(11):1827–1832. PubMed CrossRef

- Bar-Zeev Y, Lim LL, Bonevski B, et al. Nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Med J Aust. 2018;208(1):46–51. PubMed CrossRef

- Hajek P, Przulj D, Pesola F, et al. Electronic cigarettes versus nicotine patches for smoking cessation in pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(5):958–964. PubMed CrossRef

- Rayburn WF, Bogenschutz MP. Pharmacotherapy for pregnant women with addictions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(6):1885–1897. PubMed CrossRef

- Jarlenski M, Minney S, Hogan C, et al. Obstetric and pediatric provider perspectives on mandatory reporting of prenatal substance use. J Addict Med. 2019;13:258–263. PubMed CrossRef

- Angelotta C, Appelbaum PS. Criminal charges for child harm from substance use in pregnancy. J Am Acad Psychiatry L. 2017;45(2):193–203. PubMed

- Atkins DN, Durrance CP. State policies that treat prenatal substance use as child abuse or neglect fail to achieve their intended goals: study examines the effect of state policies that treat prenatal substance use as child abuse or neglect on the incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome and other factors. Health Aff. 2020;39(5):756–763. PubMed CrossRef

- Austin AE, Naumann RB, Simmons E. Association of state child abuse policies and mandated reporting policies with prenatal and postpartum care among women who engaged in substance use during pregnancy. JAMA Pediatr. 2022;176(11):1123–1130. PubMed CrossRef

- Goodman D, Whalen B, Hodder LC. It’s time to support, rather than punish, pregnant women with substance use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914135. PubMed CrossRef

- Kravitz E, Suh M, Russell M, et al. Screening for substance use disorders during pregnancy: a decision at the intersection of racial and reproductive justice. Am J Perinatol. 2023;40(6):598–601. PubMed CrossRef

- Massey SH, Decety J, Wisner KL, et al. Specification of change mechanisms in pregnant smokers for malleable target identification: a novel approach to a tenacious public health problem. Front Public Health. 2017;5:239. PubMed CrossRef

- Kendler KS, Ohlsson H, Svikis DS, et al. The protective effect of pregnancy on risk for drug abuse: a population, co-relative, co-spouse, and within-individual analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(10):954–962. PubMed CrossRef

- Edwards AC, Ohlsson H, Svikis DS, et al. Protective effects of pregnancy on risk of alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(2):138–145. PubMed CrossRef

- Patton D, Best D. Motivations for change in drug addiction recovery: turning points as the antidotes to the pains of recovery. J Drug Issues. 2024;54(3):346–366. CrossRef

- Gurka KK, Burris HH, Ciciolla L, et al. Assessment of maternal health and behavior during pregnancy in the HEALthy Brain and Child Development Study: rationale and approach. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2025;71:101494. PubMed CrossRef

- D’Onofrio BM, Rickert ME, Langström N, et al. Familial confounding of the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and offspring substance use and problems. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1140–1150. PubMed CrossRef

- Massey SH, Lieberman DZ, Reiss D, et al. Association of clinical characteristics and cessation of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use during pregnancy. Am J Addict. 2011;20(2):143–150. PubMed CrossRef

- Massey SH, Bublitz MH, Magee SR, et al. Maternal–fetal attachment differentiates patterns of prenatal smoking and exposure. Addict Behav. 2015;45:51–56. PubMed CrossRef

- Massey SH, Compton MT. Psychological differences between smokers who spontaneously quit during pregnancy and those who do not: a review of observational studies and directions for future research. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(2):307–319. PubMed CrossRef

- Level RA, Zhang Y, Tiemeier H, et al. Unique influences of pregnancy and anticipated parenting on cigarette smoking: results and implications of a within-person, between pregnancy study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2024;27(2):301–308. PubMed CrossRef

- Massey SH, Allen NB, Pool LR, et al. Impact of prenatal exposure characterization on early risk detection: Methodologic insights for the HEALthy Brain and Child Development (HBCD) study. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2021;88:107035. PubMed CrossRef

- Massey SH, Mroczek DK, Burns JL, et al. Positive parenting behaviors in women who spontaneously quit smoking during pregnancy: clues to putative targets for preventive interventions. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2018;67:18–24. PubMed CrossRef

- Lieberman DZ, Cioletti A, Massey SH, et al. Treatment preferences among problem drinkers in primary care. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2014;47(3):231–240. PubMed CrossRef

- Willenbring ML, Massey SH, Gardner MB. Helping patients who drink too much: an evidence-based guide for primary care clinicians. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(1):44–50. PubMed

- Merikangas KR, Mehta RL, Molnar BE, et al. Comorbidity of substance use disorders with mood and anxiety disorders: results of the International Consortium in Psychiatric Epidemiology. Addict Behav. 1998;23(6):893–907. PubMed CrossRef

- Massey SH, Lieberman DZ, Reiss D, et al Association of clinical characteristics and cessation of tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drug use during pregnancy. Am J Addict. 2011;20(2):143-150. PMCID: PMC3052631.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!