Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04057

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever wondered which treatments are best for your patients with an alcohol use disorder (AUD)? Have you been uncertain about which patients (and problems) you should manage and which of your patients you should refer for specialized psychological or pharmacologic interventions? Have you thought about the factors that reduce the efficacy of AUD treatments and what can be done to enhance treatment efficacy? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Ms B, a 47-year-old attorney, presented for a routine primary care visit following a 4-year gap in care. Her medical history included fibromyalgia and gastroesophageal reflux disease; her body mass index was 24 kg/m2, and she was not taking any prescribed medications.

On physical examination, her blood pressure was 147/102 mm Hg, her pulse was 89 beats/minute, and her respiratory rate was 12 breaths/minute. Laboratory results revealed a mild transaminitis (aspartate aminotransferase: 62 U/L; alanine aminotransferase: 51 U/L), while all other values were within normal limits. Her phosphatidylethanol (PEth) level was 321 ng/mL, which was consistent with heavy recent alcohol use (a PEth level >250 ng/mL generally indicates heavy or frequent drinking, while levels <80 ng/mL suggest low or moderate use).1

Ms B reported increasing stress and alcohol use (9–12 ounces of whiskey over ice, which translates to 6–8 standard drinks/day) exclusively in the evenings. She noted that trembling and diaphoresis increased throughout the day, which she attributed to anxiety. She denied having seizures or perceptual disturbances.

She expressed a desire to reduce her alcohol consumption, believing that it was contributing to her anxiety and elevated liver enzymes. Although she had previously attempted to cut back, she found sustained reduction difficult; her most successful effort lasted 4 days, following a surgical procedure.

DISCUSSION

What Types of Medications Can Help People Cut Down or Stop Drinking?

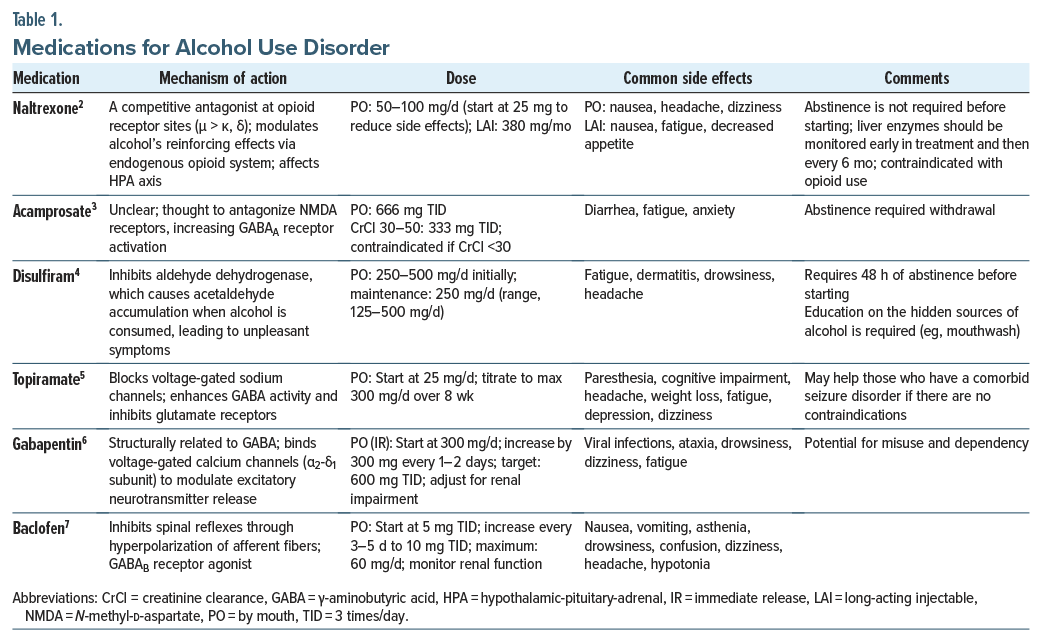

Several medications (eg, naltrexone, acamprosate) are first-line treatments to help people cut down, or stop, their alcohol use (Table 1). Naltrexone (as an oral [PO] or intramuscular [IM] preparation) reduces the reinforcing effects of alcohol consumption via µ-opioid receptor blockade.2 PO naltrexone is typically dosed at 50–100 mg/day, while the IM formulation (Vivitrol) is dosed at 380 mg every 4 weeks. Unfortunately, naltrexone is not an ideal option for those who are taking opioids for pain relief, as it is an opioid antagonist that reduces the pain-relieving effects of opioids. Overall, naltrexone is well tolerated; however, its most common side effects include nausea, decreased appetite, and fatigue.

Acamprosate reduces rates of alcohol consumption and modestly increases the duration of abstinence through modulation of glutamate in the central nervous system.3 While acamprosate is safe and typically well tolerated, doses should be reduced in those with renal failure, as acamprosate is excreted by the kidneys. One factor that limits acamprosate use is its 3 times/day dosing requirement.

While topiramate has not received US Food and Drug Administration approval for alcohol cessation, it antagonizes kainate glutamate receptors and interacts with γ-aminobutyric acid receptors to facilitate reduction of alcohol use in those with a severe AUD.5 Topiramate dosing should be increased gradually and tapered slowly (to reduce the risk of seizures), and it should not be administered to pregnant females or to women of childbearing potential (due to its teratogenic risk). Frequent side effects include weight loss, mood changes, cognitive blunting, and depression.

Gabapentin (which is often dosed at 600 mg 3 times/ day) facilitates abstinence from alcohol use by reducing the extent of drinking as well as by enhancing mood and sleep and reducing alcohol cravings.6 Other agents used in the management of AUDs include baclofen and ondansetron, although data on their efficacy have been inconclusive.7,8 Disulfiram creates negative reinforcement by precipitating undesirable physical reactions when alcohol is consumed (via aldehyde dehydrogenase’s inhibition of acetaldehyde). Accumulation of acetaldehyde leads to nausea, vomiting, sweating, headaches, and palpitations. Disulfiram’s utility has been limited, as it requires patients to be highly motivated or supervised, since some patients discontinue their use of disulfiram before resuming drinking. Disulfiram should be avoided in those with severe cardiovascular disease, since heart failure and death may follow the initiation of disulfiram in those with severe myocardial disease. Disulfiram should also be avoided in those with psychosis, as disulfiram may worsen psychosis.4

What Are the Best Strategies to Manage Alcohol Withdrawal?

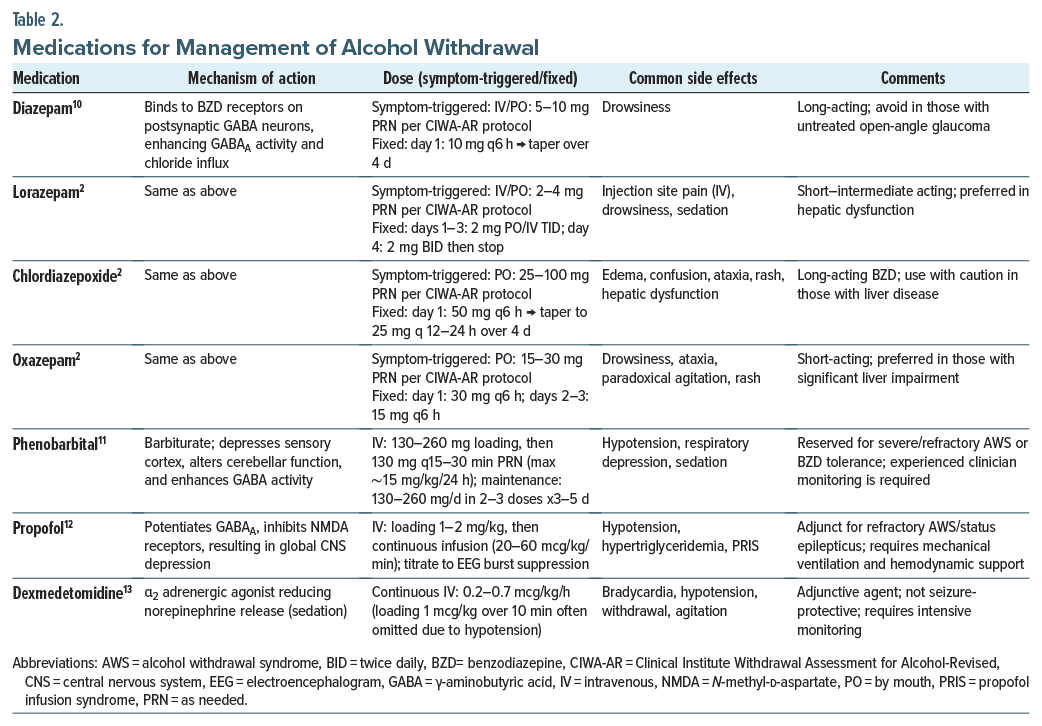

The heterogeneity of AUDs makes it difficult to recommend a single protocol for all individuals who require alcohol detoxification. However, the management of alcohol withdrawal usually involves a symptom-triggered benzodiazepine (BZD)–based withdrawal protocol, in which the dosing and timing of BZD administration are based on symptom severity (Table 2). Standardized assessments to assess the severity of alcohol withdrawal include the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol-Revised.9 Symptom-triggered interventions can be tailored to each patient to ensure that treatment is delivered only when it is needed (thereby avoiding the complications associated with oversedation) and that each patient receives as much as is needed to quell the withdrawal state. The implications of such treatment protocols include shortening the duration of treatment and reducing the cumulative BZD dose by a factor of 4. Standing orders for BZD tapering, while not recommended, may be warranted in some individuals (eg, when medical confounders resemble signs of withdrawal or when a patient may be attempting to deceive practitioners about their alcohol use history).2 Fixed-dose regimens warrant close monitoring for excessive sedation and respiratory depression.7

The BZDs most used in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal include diazepam, lorazepam, and chlordiazepoxide. Chlordiazepoxide and diazepam are commonly used in outpatient settings, while lorazepam is often preferred for inpatients. The half-life of diazepam is approximately 48 hours, with its active metabolite lasting up to 100 hours. This provides an additional advantage in AUD by allowing a form of self-tapering. However, liver function should be carefully considered, as diazepam is metabolized hepatically.10 Certain BZDs (ie, oxazepam, temazepam, lorazepam) require only glucuronidation (rather than oxidative metabolism) and are preferred for those with impaired hepatic function. Those who are unable or unwilling to take oral medications can receive lorazepam intravenously or IM.

Alternatives to BZDs include phenobarbital, which has a similar efficacy and safety profile to BZDs and has been considered superior to BZDs in those who are tolerant to BZDs, or in surgical trauma patients, in whom it is difficult to use symptom-triggered treatment.11 Dexmedetomidine and propofol have also been used.12,13 Although ethanol can be used to manage alcohol withdrawal, it can be challenging to titrate, it possesses adverse metabolic effects, and it increases the potential for drug-drug interactions. Other agents include antiepileptic drugs, although they are generally considered inferior to BZDs in the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Supportive care helps to minimize complications from alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Among inpatients, the risks of falls and aspiration must be considered; hence, overmedication should be avoided. Calming can also be achieved by the addition of quetiapine, olanzapine, or haloperidol.9

What Types of Psychotherapy Are Available to Help People Refrain From Drinking Alcohol?

Several forms of individual and group psychotherapy help individuals reduce or abstain from alcohol use. Psychotherapies can be started as a stand-alone treatment or in conjunction with pharmacologic options; strategies are often tailored to address the needs and goals of the individual. While evidence-based outpatient therapies typically follow a frequency of 1 session/week, intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) deliver group-based care 3 or more days per week and may be helpful for patients who would benefit from greater consistency and accountability. Many contemporary psychotherapies adopt a harm-reduction philosophy, which embraces the notion that there are multiple pathways to recovery. Abstinence goals are accepted and supported under harm-reduction models, but strict adherence to maintaining abstinence is not a requirement for participation and is not the only metric of success. Instead, a harm-reduction approach consists of practices and policies that are intended to minimize the negative physical, social, and functional impacts of substance use and to enhance the quality of one’s life. These approaches can offer considerable benefits to individuals who are not interested in abstinence or who feel incapable of sustaining abstinence.14

Effective individual and group psychotherapies frequently include motivational interviewing (MI) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques.15,16 MI is a collaborative, patient-centered method of communication that explores ambivalence, enhances change-oriented self-talk, and bolsters intrinsic motivation for behavioral change. Some studies suggest that MI may be particularly beneficial for those with long-term AUD.17 In turn, CBT encompasses a broad range of protocols through which individuals learn and practice skills to challenge unhelpful thought processes, cope with cravings, establish personal and interpersonal boundaries, and increase confidence in their ability to manage difficult situations without drinking alcohol. Relapse prevention is a common CBT approach for AUD that helps individuals build awareness of the antecedents and consequences of their alcohol use and learn alternative coping skills to disrupt problematic use patterns.18 More recent versions of CBT, referred to as “third-wave” approaches, feature mindfulness skills developed to assist individuals in slowing down, nonjudgmentally observing their cravings, and responding in ways that are more consistent with their values and goals. These options include acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT)19,20 and mindfulness-based relapse prevention.21

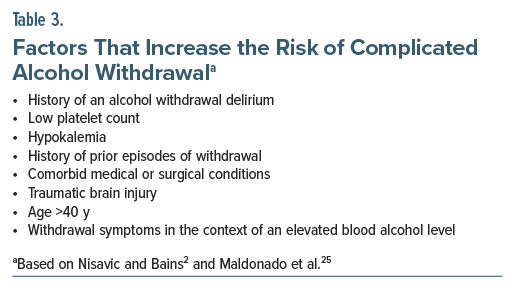

Further, since AUDs commonly arise in the context of co-occurring psychosocial stress, emotional dysregulation, or mental health sequela (eg, anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress), psychotherapies can foster insight and subsequently treat co-occurring conditions and underlying functions of an individual’s alcohol use (Table 3). These “functions of use” vary from person to person but tend to sustain drinking behaviors and can pose a risk for returning to heavy use if left unaddressed. Many CBT approaches for AUD have secondary effects on improving mental health functioning,22 and recent studies have found that integrated treatments such as the concurrent treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders (SUDs) and integrated anxiety-substance use treatments are superior to substance use treatment alone for dually diagnosed individuals.23 In addition, there is evidence to support the incorporation of dialectical behavior therapy skills training—another third-wave CBT approach—to foster transdiagnostic distress tolerance, emotion regulation, and interpersonal communication skills-building among individuals with AUD and a co-occurring psychiatric condition.24

How Do the Various Forms of Psychotherapy Facilitate Change and Abstinence From Alcohol?

Several psychotherapeutic approaches support AUD treatment at different stages of readiness for change. MI and motivational enhancement therapy (MET) are designed to address ambivalence, and they are particularly effective during precontemplation and contemplation stages of change.26 MI may be delivered in a semistructured interview format, utilizing open-ended questioning, empathic dialogue, prioritization of patient-defined goals, and the elicitation of “change talk” to enhance intrinsic motivation for behavioral change.

CBT and mindfulness-based interventions are particularly effective during the action and maintenance phases. These modalities provide individuals with tools needed to manage stress, respond adaptively to cues and triggers, and enhance cognitive flexibility to reduce reliance on automatic or maladaptive behaviors.27

ACT, which emphasizes a values-based approach, has shown preliminary evidence of efficacy in the treatment of AUD.20 ACT may be applied across all stages of change—from precontemplation through maintenance—by fostering psychological flexibility and alignment with personal values. Given its limited evidence base, ACT is currently recommended as an adjunctive treatment.

Structured group therapy, commonly offered through IOPs, and peer support groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) and Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART) Recovery,28,29 are also integral components of comprehensive AUD treatment. IOPs, in particular, may be especially valuable during the action stage, providing a higher level of care, structure, and accountability.30

A recent meta-analysis found that MET and couples therapy were associated with significant reductions in the number of drinking days, while supportive psychotherapy was linked to reductions in the quantity of alcohol consumed per drinking day.31 Another meta-analysis concluded that multisession, face-to-face interventions that combined MI with CBT were superior to other treatment approaches.32 Collectively, these therapeutic modalities are complementary when facilitating a reduction in alcohol consumption or sustained abstinence among individuals with an AUD.

What Determines Whether Your Patient Should Embark Upon Inpatient or Outpatient Care?

Determination of the level of care for patients with an AUD depends largely on the severity of their withdrawal symptoms, individual preferences, the recovery environment, and their ability to participate in treatment. Some factors (eg, imminent risk for suicide) may require an involuntary psychiatric admission, where care for alcohol withdrawal can be delivered alongside other treatments to reduce the risk of suicide.33

Factors that increase the risk of developing complicated alcohol withdrawal should prompt consideration of a hospital admission (Table 3).34 The Patient Placement Criteria of the American Society of Addiction Medicine evaluates 6 biopsychosocial domains (ie, acute intoxication and withdrawal, biomedical, emotional, behavioral, cognitive, readiness to change, relapse, and recovery) to guide assessment of the level of care needed, along with validated assessment tools (eg, the Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale, with scores greater than 4 indicating a severe risk for alcohol withdrawal).25,35 In the absence of the above risk factors, most treatment for AUD can be accomplished on an outpatient basis.

Evidence-based psychological treatments and community support can address several domains that are impacted by chronic alcohol use (eg, the ability to form relationships, make decisions, develop vocational skills, enhance a view of oneself, and maintain a sense of purpose).2 Participation in self-help groups (eg, AA) offers no-cost in-person and online services through peer support, which provides an effective means of facilitating spiritual growth and sobriety.28 Those with greater psychological stability and less severe alcohol use histories may benefit from SMART Recovery groups.29 CBT and MI also offer validated and effective methods of addressing drinking behaviors; however, they require a patient’s willingness to engage and remain in treatment.27,36

When (and How) Can You Arrange for an Involuntary Commitment for an AUD?

In situations where all voluntary treatment options have proven ineffective, 37 US states and the District of Columbia have laws in place that allow involuntary treatment for SUDs, but the application varies considerably.37 Involuntary commitment for AUD is governed by state-specific laws that permit civil commitment when an individual is deemed to pose an immediate risk to themselves or to others due to substance use. Typically, a family member, physician, or other authorized individual can petition the court to initiate the process, which often involves law enforcement for transportation and court accompaniment.38,39 The frequency and application of such laws vary by jurisdiction—from virtually no cases to thousands annually. Statutes like Casey’s Law in Kentucky40 and the CARE Act in California41 reflect recent legislative trends toward expanding civil commitment options for SUDs.42

In Massachusetts, individuals may be committed under General Laws Chapter 123, Section 35, which allows for placement in facilities that may be operated by sheriff’s departments or the Department of Correction.43 However, the historical roots of commitment laws are deeply intertwined with the criminalization of addiction and racial bias, as illustrated by cases like Powell v Texas (1968),44 and these laws continue to disproportionately impact black, Hispanic, and Native American communities with limited treatment access.45–47

Although civil commitment laws are increasingly used—especially in response to rising rates of SUDs (affecting 17.1% of those aged 12 years or older in 2023 [48.5 million])48 and drug overdose deaths related to fentanyl and methamphetamine—there remains limited evidence supporting the efficacy of involuntary treatment.49,50 Studies comparing voluntary versus involuntary SUD treatment suggest that involuntary treatment should be used as a last resort for individuals who are unable to engage voluntarily.

Because these laws are state-regulated, specific criteria and processes vary. In most states, clinical eligibility hinges on the presence of imminent risk to self or others. A family member or physician typically completes state-specific forms and provides clinical documentation to support the petition.

Involuntary treatment should only be considered when less restrictive treatment options have failed and when there is an immediate risk to life or safety. While there may be limited clinical utility in certain cases, involuntary treatment for SUD should be administered within the health care system rather than through correctional facilities.

Which Patient, Provider, and System Factors Interfere With Successful Screening, Treatment, and Referral?

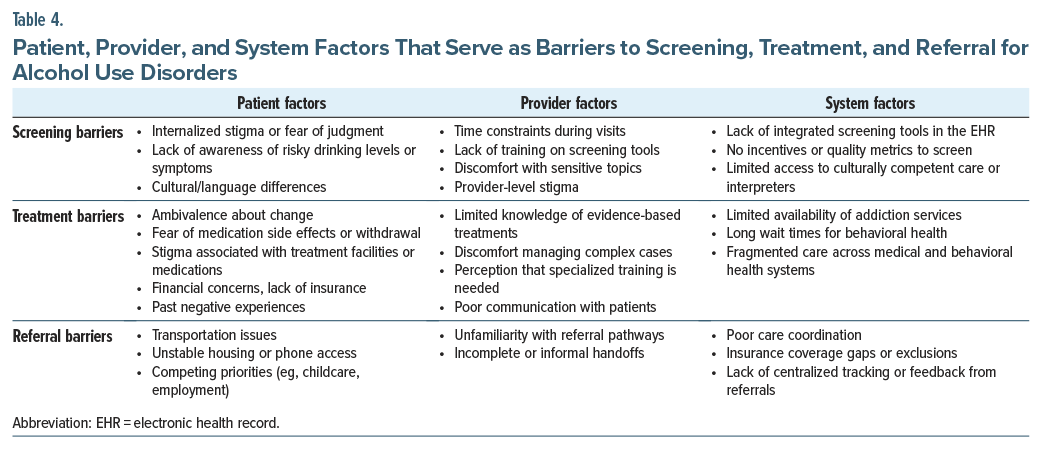

Due to myriad barriers to care (Table 4), fewer than 10% of patients with an AUD access treatment programs.51 On the patient side, barriers include a limited awareness that there might be a problem and limited knowledge of the recommended weekly maximum alcohol drinks. Unfortunately, many people believe that small amounts of alcohol have cardioprotective effects, which leads them to perceive moderate alcohol use as being beneficial to their health. Other patient-level barriers include financial concerns, limited access to care (including a lack of health insurance), and difficulty finding providers who are comfortable with, and experienced in, treating AUD. For centuries, stigma—closely tied to the perception of alcohol use as a personal choice and the shame associated with it—remains one of the primary reasons that individuals avoid seeking treatment.52 Cultural beliefs and norms also contribute to treatment avoidance.

Provider-level factors include limited training in the management of AUDs, the perception that patients are choosing to continue engaging in excessive consumption despite adverse health consequences, and burnout that results from the challenges of remaining engaged with those who struggle with AUD despite treatment. Additional barriers include limited time during patient visits and unfamiliarity with treatment tools, or difficulty addressing alcohol use compassionately, even when screening tools are available.53 System-level factors include inequities in access to care, limited insurance coverage, and a shortage of providers and care coordinators.54

What Happened to Ms B?

Ms B was counseled on the signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal and advised to complete an inpatient withdrawal protocol. However, given her lack of a history of complicated withdrawal, outpatient management was deemed safe by her health care provider. She declined residential treatment due to work obligations and opted for an outpatient chlordiazepoxide taper, along with information about gradual alcohol reduction strategies, which were supported by her primary care provider.

Naltrexone (50 mg daily) was initiated, along with thiamine and folic acid, which she tolerated well. Over the next 2 months, her alcohol consumption decreased to roughly 2 drinks each night, but she continued to experience cravings. Naltrexone was increased (to 100 mg daily), although she received minimal benefit, and nausea was prominent. Acamprosate (666 mg 3 times/ day) was added, which led to a marked reduction in her cravings for alcohol and her anxiety. Within the next 3 weeks, she reduced her alcohol use to 1–2 drinks per week, and she no longer drank alone.

At her 3-month follow-up, her liver enzymes had normalized, and her PEth level (80 ng/mL) was consistent with low alcohol consumption. She engaged in biweekly CBT and joined SMART Recovery for peer support. After 6 months, Ms B remained largely abstinent, with normalized liver function tests, improved blood pressure, and sustained gains in mood and well-being.

CONCLUSION

AUDs are prevalent and problematic, as are complications associated with drastic reductions in alcohol use, as they can precipitate a potentially lethal alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Although no single protocol has been adopted for use in alcohol detoxification, alcohol withdrawal is usually managed with a symptom-triggered BZD-based protocol, in which the timing and dosing of BZDs are based on symptom severity; however, other agents (eg, phenobarbital, dexmedetomidine, propofol) have also been efficacious. To cut down or stop drinking alcohol, pharmacologic agents (eg, naltrexone, acamprosate, gabapentin, topiramate, baclofen, disulfiram), psychotherapies (eg, CBT, ACT), and self-help groups (eg, AA, SMART Recovery) play a role. Moreover, patient, provider, and systemic factors can each contribute to delays in screening, treatment, and referral for treatment of AUDs, and knowledge of these factors can lead to strategies that can overcome barriers to care. In circumstances when all treatment approaches have failed, most states have laws that allow for the involuntary treatment of individuals with AUDs.

Article Information

Published Online: January 13, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04057

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: August 12, 2025; accepted October 2, 2025.

To Cite: Terechin O, Lento RM, Braford MB, et al. Treatment and referral for alcohol use disorders in primary care. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25f04057.

Author Affiliations: Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Terechin); Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Lento, Stern); Lewis Gale Medical Center, Salem, Virginia (Braford, Mastronardi)

Corresponding Author: Theodore A. Stern, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, 55 Fruit St, WRN 606, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

Terechin, Lento, Braford, and Mastronardi are co-first authors; Stern is the senior author.

Financial Disclosure: Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Terechin, Lento, Braford, and Mastronardi report no relevant financial relationships.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- First-line pharmacologic treatments to help people cut down, or stop, their alcohol use include naltrexone (which reduces the reinforcing effects of alcohol consumption via µ-opioid receptor blockade) and acamprosate (which works through modulation of glutamate in the central nervous system). Additional agents that are helpful in the management of alcohol use disorders include topiramate, gabapentin, baclofen, and disulfiram.

- Although there is no single approach to those who require alcohol detoxification, the management of alcohol withdrawal usually involves a symptom-triggered benzodiazepine (BZD)-based withdrawal protocol, in which the dosing and timing of BZD administration are based on symptom severity. Alternatives to BZDs include phenobarbital, dexmedetomidine, and propofol.

- Standardized assessments to assess the severity of alcohol withdrawal include the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol-Revised.

- Contemporary psychotherapies adopt a harm-reduction philosophy that embraces the notion that there are multiple pathways to recovery.

- In situations in which all voluntary treatment options have proven ineffective, most US states have laws that allow for the involuntary treatment for substance use disorders.

References (54)

- Perilli M, Toselli F, Franceschetto L, et al. Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) in blood as a marker of unhealthy alcohol use: a systematic review with novel molecular insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):12175. PubMed CrossRef

- Nisavic M, Bains A. Substance use disorders. In: Stern TA, Beach SR, Smith FA, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Handbook of General Hospital Psychiatry. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2025:203–227.

- Rösner S, Hackl-Herrwerth A, Leucht S, et al. Acamprosate for alcohol dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010(9):CD004332.

- Stokes M, Patel P, Abdijadid S. Disulfiram. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Accessed July 23, 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459340/

- Fluyau D, Kailasam VK, Pierre CG. A Bayesian meta-analysis of topiramate’s effectiveness for individuals with alcohol use disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2023;37(2):155–163. PubMed CrossRef

- Kranzler HR, Feinn R, Morris P, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114(9):1547–1555. PubMed CrossRef

- Agabio R, Saulle R, Rösner S, et al. Baclofen for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;1(1):CD012557. PubMed CrossRef

- Seneviratne C, Gorelick DA, Lynch KG, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pharmacogenetic study of ondansetron for treating alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(10):1900–1912. PubMed CrossRef

- Schuckit MA. Recognition and management of withdrawal delirium (delirium tremens). N Engl J Med. 2014;371(22):2109–2113. PubMed CrossRef

- Weintraub SJ. Diazepam in the treatment of moderate to severe alcohol withdrawal. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(2):87–95. PubMed CrossRef

- Nishimura Y, Choi H, Colgan B, et al. Current evidence and clinical utility of phenobarbital for alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2023;112:52–61. PubMed CrossRef

- Shirk L, Reinert JP. The role of propofol in alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review. J Clin Pharmacol. 2025;65(2):170–178. PubMed CrossRef

- Linn DD, Loeser KC. Dexmedetomidine for alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49(12):1336–1342. PubMed CrossRef

- Witkiewitz K, Heather N, Falk DE, et al. World Health Organization risk drinking level reductions are associated with improved functioning and are sustained among patients with mild, moderate and severe alcohol dependence in clinical trials in the United States and United Kingdom. Addiction. 2020;115(9):1668–1680. PubMed CrossRef

- Morgenstern J, Longabaugh R. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for alcohol dependence: a review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiction. 2000;95(10):1475–1490. PubMed CrossRef

- Morgenstern J, Kuerbis A, Houser J, et al. Dismantling motivational interviewing: effects on initiation of behavior change among problem drinkers seeking treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2017;31(7):751–762. PubMed CrossRef

- Yao J, Wang B, Liu S, et al. Grouping motivational interviewing for alcohol craving in individuals with alcohol use disorder: the influence of drinking history on its efficacy. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2025;275(7):2141–2149. PubMed CrossRef

- Hendershot CS, Witkiewitz K, George WH, et al. Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Pol. 2011;6:17. PubMed CrossRef

- Byrne SP, Haber P, Baillie A, et al. Systematic reviews of mindfulness and acceptance and commitment therapy for alcohol use disorder: should we be using third wave therapies?. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019;54(2):159–166. PubMed CrossRef

- Thekiso TB, Murphy P, Milnes J, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of alcohol use disorder and comorbid affective disorder: a pilot matched control trial. Behav Ther. 2015;46(6):717–728. PubMed CrossRef

- Ramadas E, Lima MP, Caetano T, et al. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based relapse prevention in individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Behav Sci. 2021;11(10):133. PubMed CrossRef

- Back SE, Jarnecke AM, Norman SB, et al. State of the science: treatment of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders. J Trauma Stress. 2024;37(6):803–813. PubMed CrossRef

- Wolitzky-Taylor K. Integrated behavioral treatments for comorbid anxiety and substance use disorders: a model for understanding integrated treatment approaches and meta-analysis to evaluate their efficacy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023;253:110990. PubMed CrossRef

- Cavicchioli M, Calesella F, Cazzetta S, et al. Investigating predictive factors of dialectical behavior therapy skills training efficacy for alcohol and concurrent substance use disorders: a machine learning study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;224:108723. PubMed CrossRef

- Maldonado JR, Sher Y, Ashouri JF, et al. The “Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale” (PAWSS): systematic literature review and pilot study of a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol. 2014;48(4):375–390. PubMed CrossRef

- Haber PS. Identification and treatment of alcohol use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2025;392(3):258–266. PubMed CrossRef

- Magill M, Ray L, Kiluk B, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: treatment efficacy by contrast condition. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2019;87(12):1093–1105. PubMed CrossRef

- Kelly JF, Humphreys K, Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;3(3):CD012880. PubMed CrossRef

- Kelly JF, Levy S, Matlack M, et al. Who affiliates with SMART Recovery? A comparison of individuals attending SMART Recovery, Alcoholics Anonymous, both, or neither. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2023;47(10):1926–1942. PubMed CrossRef

- McCarty D, Braude L, Lyman DR, et al. Substance abuse intensive outpatient programs: assessing the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(6):718–726. PubMed CrossRef

- Zhang P, Zhan J, Wang S, et al. Psychological interventions on abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:1815–1830. PubMed CrossRef

- Tan CJ, Shufelt T, Behan E, et al. Comparative effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in adults with harmful use of alcohol: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Addiction. 2023;118(8):1414–1429. PubMed CrossRef

- Bowden B, John A, Trefan L, et al. Risk of suicide following an alcohol-related emergency hospital admission: an electronic cohort study of 2.8 million people. PLoS One. 2018;13(4):e0194772. PubMed CrossRef

- Goodson CM, Clark BJ, Douglas IS. Predictors of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(10):2664–2677. PubMed CrossRef

- Magura S, Staines G, Kosanke N, et al. Predictive validity of the ASAM Patient Placement Criteria for naturalistically matched vs mismatched alcoholism patients. Am J Addict. 2003;12(5):386–397. PubMed CrossRef

- Coriale G, Fiorentino D, De Rosa F, et al. Treatment of alcohol use disorder from a psychological point of view. Riv Psichiatr. 2018;53(3):141–148. PubMed CrossRef

- Legislative Analysis and Public Policy Association. Involuntary commitment of those with substance use disorders: summary of state laws. 2024. Accessed August 10, 2025. https://legislativeanalysis.org/involuntary-commitment-of-those-with-substance-use-disorders-summary-of-state-laws-with-substance-use-disordersnvoluntary-commitment-and-guardianship-laws-pdf/

- Jain A, Christopher P, Appelbaum PS. Civil commitment for opioid and other substance use disorders: does it work?. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(4):374–376. PubMed CrossRef

- Coffey KE, Aitelli A, Milligan M, et al. Use of involuntary emergency treatment by physicians and law enforcement for persons with high-risk drug use or alcohol dependence. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(8):e2120682. PubMed CrossRef

- Casey’s law - office of drug control policy. Accessed July 26, 2025. https://odcp.gov/Resources/Pages/Caseys-Law.aspx

- Disability Rights California. Information on CARE Act (SB 1338, Umberg 2022). Accessed July 27, 2025. https://www.disabilityrightsca.org/latest-news/disability-rights-california-information-on-care-act-sb-1338-umberg-2022

- Bazazi AR. Commentary on Rafful et al. (2018): Unpacking involuntary interventions for people who use drugs. Addiction. 2018;113(6):1064–1065. PubMed CrossRef

- General Law - Part I, Title XVII, Chapter 123, Section 35. Accessed August 10, 2025. https://malegislature.gov/Laws/GeneralLaws/PartI/TitleXVII/Chapter123/Section35

- Powell v. Texas, 392 US 514. 1968. Accessed July 26, 2025. https://supreme.com/cases/federal/us/392/514/

- Friedman JR, Hansen H. Evaluation of increases in drug overdose mortality rates in the US by race and ethnicity before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79(4):379–381. PubMed CrossRef

- Jones AA, Waghmare SA, Segel JE, et al. Regional differences in fatal drug overdose deaths among Black and White individuals in the United States, 2012-2021. Am J Addict. 2024;33(5):534–542. PubMed CrossRef

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2021 National Survey on drug Use and health (NSDUH) releases. 2021. Accessed July 26, 2025. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health/national-releases/2021

- Minkoff K. Civil commitment for people with substance use disorders: Balancing benefits and harms. Psychiatr Serv. 2024;75(12):1283–1284. PubMed CrossRef

- Bahji A, Leger P, Nidumolu A, et al. Effectiveness of involuntary treatment for individuals with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Can J Addict. 2023;14(4):6–12. CrossRef

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(9):911–923. PubMed CrossRef

- Venegas A, Donato S, Meredith LR, et al. Understanding low treatment seeking rates for alcohol use disorder: a narrative review of the literature and opportunities for improvement. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2021;47(6):664–679. PubMed CrossRef

- Keyes KM, Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, et al. Stigma and treatment for alcohol disorders in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(12):1364–1372. PubMed CrossRef

- Williams EC, Achtmeyer CE, Young JP, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of alcohol use disorder pharmacotherapy in primary care: a qualitative study in five VA clinics. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(3):258–267. PubMed CrossRef

- Koob GF. Alcohol use disorder treatment: problems and solutions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2024;64:255–275. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!