Menstrual psychosis was introduced by Krafft-Ebing as “psychosis menstrualis” in his monograph.1 Described as a forgotten disorder, less is known about it today.2 A search in PubMed through January 2025 for “menstrual” and “psychosis” in “title” among all documents published in English revealed approximately 30 case studies and no clinical trials.3 Cases are still being reported and discussed to date due to their varying presentations and challenges in diagnosis and treatment.2,4–6 Additionally, menstrual psychosis is not included in any current nosological system, posing challenges to clinicians for its identification, management, and prognosis.2,3,7–10 Menstrual psychosis has been reported with catatonia as well.11 Brockington2 attempted to define menstrual psychosis with the following characteristics: (1) acute onset, against a background of normality; (2) brief duration, with full recovery; (3) clinical signs of psychotic features including confusion, stupor and mutism, delusions, hallucinations, or a manic syndrome; and (4) a circa- mensual (approximately monthly) periodicity in rhythm with the menstrual cycle. Further, it was classified into premenstrual psychosis, catamenial psychosis, mid-cycle psychosis, and epochal menstrual psychosis based on its onset and offset within the menstrual cycle. Here, we present 2 cases of menstrual psychosis.

Case 1

A 22-year-old woman presented to the outpatient department (OPD) of a psychiatric teaching hospital in India with chief complaints of sudden aggressive abusive behavior, muttering to self, smiling to self, decreased sleep, overgrooming, increased talk, and wandering for 5 years. History revealed that the patient would start having these symptoms 7–8 days before her menses, and they would gradually increase and then subside 2–3 days after her menses. The patient presented to us on the fourth day of her menstruation.

The patient would abruptly start getting aggressive and irritable 7–8 days before her menses. Family members would notice her muttering and smiling to herself and gesturing for no apparent reason. She would not sleep at night and would wander around the house and sometimes leave and have to be brought back home. She would also start talking irrelevantly, and it would be difficult to stop her. She would keep looking at herself in the mirror and change clothes multiple times a day. She would start throwing things around the house, and it was difficult to control her. These symptoms would last for 10–15 days and gradually subside 2–3 days after her menses. She has had regular menstrual cycles from menarche at the age of 14 years, with no history suggestive of similar presentation until 5 years ago. There was no history of hearing voices others cannot hear, her thoughts being known to others, low mood, self-harm, or suicidal attempt. A mental status examination (MSE), on general appearance and behavior, revealed hallucinatory behavior with muttering and smiling to herself. She was irritable. Thought content revealed that she believed that her mother was doing everything, and it was because of her mother that things were not fine. She also stated that her mother adds something to her food to make her lose her mind and abandon her, suggesting delusion of persecution. According to the patient, she was forced to come for a visit to the hospital. Her judgment and insight were impaired and grade 1, respectively.

Case 2

A 34-year-old married woman presented to the OPD of a psychiatric teaching hospital in India with chief complaints of decreased sleep, irrelevant and increased talk, muttering to self, gesturing, aggressive and abusive behavior, and hyperreligiosity for the last 3 years. The symptoms would start 5–7 days before her menses, last for 8–12 days, and subsequently resolve on their own. The patient presented to the OPD on the third day of her menses.

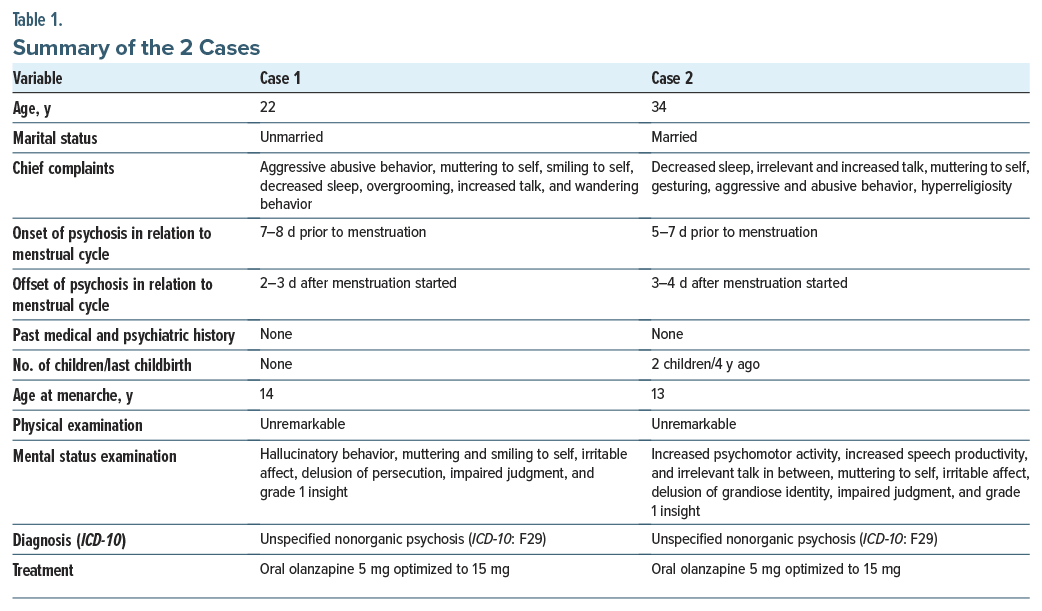

The symptoms would start with decreased sleep. Family members would notice that she would not sleep at night, and she was seen talking to herself and gesturing as if she were talking with someone. When family members tried to communicate with her, she would get irritable and became abusive. She would suddenly get aggressive and try to hit the family members, and it was difficult to control her. She would keep talking the entire day about things that made no sense to her family members. She would also talk about various Hindu goddesses and say that she had the power to control everything, as she could directly communicate with them. These symptoms would begin 5–7 days before her menses and would gradually increase over the next 5–6 days and subside 3–4 days after her menses. She had regular menstrual cycles from menarche at age 13 years with no history suggestive of a similar presentation until 3 years ago. Her last childbirth was 4 years ago. The MSE revealed increased psychomotor activity, increased speech productivity, and irrelevant talk in between. She was muttering to herself during the consultation with the doctor. Her affect was irritable. She reported that she has the power of Goddess Kali, and she runs the entire world with these powers. She further elaborated that no one can destroy her or do any harm to her as she can do anything and everything, suggesting she had a delusion of grandiose identity. Her judgment was impaired. Her insight into her illness was grade 1, as she denied having any illness. Table 1 provides a summary of the 2 cases.

Discussion

According to Brockington classification,2 both the cases presented here fall into premenstrual psychosis, where psychosis starts during the second half of the cycle and resolves after the onset of menstrual bleeding. While most of the previously reported cases were after menarche or childbirth, neither of the cases presented here had such an association. As the etiology was of unknown origin, we resorted to unspecified nonorganic psychosis as a provisional diagnosis for both cases.

Menstrual psychosis is a serious mental illness and has a significant impact on the quality of life, and early recognition and treatment are essential. Little is known about the etiology and neurobiology of menstrual psychosis. Shah et al10 discussed a possible biopsychosocial model of disease where biological factors included excess estrogen, decreased progesterone, and sodium and water retention due to aldosterone. Negative attitudes toward femininity leading to castration anxiety and disturbed ego defense could be potential psychosocial factors. Estrogen has been found to play a protective role in psychosis.12 The estrogen hypothesis postulates that a sustained increase in estrogen levels, which has a priming effect on the brain, followed by a sudden decrease triggers menstrual psychosis.13,14 Abnormality of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis has also been suggested as a factor for menstrual psychosis.2,15 The association with several pituitary- secreted hormones and overactivity of the HPA axis has been mentioned in the literature along with their interaction with the serotonin/ dopamine system.16 Considering its association with anovulatory cycles and luteal problems and its cyclical nature, the hypothalamus has been implicated in the etiology of menstrual psychosis.17 Both patients improved with the use of olanzapine. Similar improvement with the use of neuroleptics has also been mentioned in the literature.2,14,18,19 While assessing psychosis of any nature among women, clinicians should keep periodicity in mind. These cases add to the case studies on menstrual psychosis and to the sparse literature of varying presentations of menstrual psychosis until it is studied systematically in the future.

Article Information

Published Online: August 19, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25cr03943

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25cr03943

Submitted: February 18, 2025; accepted May 12, 2025.

To Cite: Malik I, Kamila AS, Khanra S, et al. Two cases of menstrual psychosis: not to be forgotten. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25cr03943.

Author Affiliations: Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, India (all authors).

Corresponding Author: Sourav Khanra, MD, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi 834006, India ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Consent was received from the patients to publish the case reports, and information has been de-identified to protect patient anonymity.

ORCID: Sourav Khanra: https://ocid.org/0000-0002-8684-6773

References (19)

- Krafft-Ebing R. Psychosis Menstrualis: Eine Klinischforensische Studie. Enke; 1902.

- Brockington I. Menstrual psychosis. World Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):9–17. PubMed

- Al-Sibani N, Al-Maqbali M, Mahadevan S, et al. Psychiatric, cognitive functioning and socio-cultural views of menstrual psychosis in Oman: an idiographic approach. BMC Women’s Health. 2020;20(1):215. PubMed CrossRef

- Desmilleville. Observation addressée à M. Vandermonde, sur unefille que l’on croyoit possédée. J Méd Chir. 1759;10:408–415.

- Gilmore A, Cottrell TJ, Chen SE. Challenges in diagnosis, treatment and coordination of care of menstrual psychosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2023;16(4):e251555. PubMed CrossRef

- Krafft-Ebíng V. Untersuchungen über Irresein zur Zeit der Menstruation. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr. 1878;8(1):65–107.

- The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Diagnostic Criteria for Research. World Health Organization, 1993.

- International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11), World Health Organization (WHO) 2019. https://icd.who.int/browse11.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2013.

- Shah AB, Vahia VN, Yadav R, et al. Menstrual psychosis: a case report. Indian J Psychiatry. 2003;45(2):61–62. PubMed

- O’Mahony B. A case of pre-menstrual psychosis with catatonic symptoms. Psychiatry Res Case Rep. 2022;1(2):100065.

- Riecher-Rössler A. Oestrogens, prolactin, hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, and schizophrenic psychoses. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(1):63–72. PubMed

- Deuchar N, Brockington I. Puerperal and menstrual psychoses: the proposal of a unitary etiological hypothesis. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1998;19(2):104–110. PubMed CrossRef

- Thippaiah SM, Nagaraja S, Birur B, et al. An interesting presentation about cyclical menstrual psychosis with an updated review of literature. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2018;48(3):16–21. PubMed

- Kitayama I, Yamaguchi T, Harada M, et al. Periodic psychoses and hypothalamo-pituitary function. Mie Med J. 1984;34:127–138.

- Hochman KM, Lewine RR. Age of menarche and schizophrenia onset in women. Schizophr Res. 2004;69(2–3):183–188. PubMed CrossRef

- Schenck CH, Mandell M, Lewis GM. A case of monthly unipolar psychotic depression with suicide attempt by self-burning: selective response to bupropion treatment. Compr Psychiatry. 1992;33(5):353–356. PubMed CrossRef

- Ray R, Paul I. Menstrual psychosis: a not so forgotten reality. Indian J Psychiatry. 2020;62(5):p585–p587. CrossRef

- Vengadavaradan A, Sathyanarayanan G, Kuppili PP, et al. Is menstrual psychosis a forgotten entity? Indian J Psychol Med. 2018;40(6):574–576. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!