Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25f03984

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever wondered which gastrointestinal (GI) complications of clozapine therapy are prevalent, problematic, and potentially life-threatening? Have you been uncertain about what the workup of GI symptoms might entail? Have you puzzled over which bowel regimens should be ordered? Have you considered how you might manage clozapine dosages and blood levels as well as those of other coadministered medications? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Ms A, a 65-year-old woman with schizophrenia who had required multiple psychiatric hospitalizations, presented to the emergency department (ED) with worsening abdominal pain, persistent nausea, and no bowel movements for the past 5 days. She had been receiving clozapine (200 mg in the morning and 500 mg at night) for more than 20 years; this regimen had facilitated relative psychiatric stability. In the ED, her clozapine level was supratherapeutic at 737 ng/mL (typical therapeutic range: 350–450 ng/mL). She had also been receiving ziprasidone (80 mg twice daily); olanzapine (10 mg as needed) had been added several weeks earlier due to worsening of psychotic symptoms, including command hallucinations.

Her medical history was notable for chronic constipation and gastroesophageal reflux disorder, which were managed with dietary adjustments and laxatives; however, her acutely increased constipation had become problematic despite these interventions.

Physical examination revealed hypotension, with a blood pressure of 100/60 mm Hg, abdominal distension, decreased bowel sounds, and abdominal tenderness. Laboratory findings included leukocytosis (white blood cell count: 14,000 mm3) and mild hypokalemia (3.5 mEq/L). An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed that Ms A had a small bowel obstruction that was consistent with a paralytic ileus, likely related to clozapine-induced GI hypomotility (CIGH).

DISCUSSION

What Is Clozapine, and How Does It Differ From Other Antipsychotics?

Initially identified in 1959, clozapine was the first medication described as an atypical antipsychotic because, in contrast to typical antipsychotics, it did not produce significant extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS).1,2 Compared with typical antipsychotics, clozapine is also less likely to elevate prolactin levels or to induce tardive dyskinesia (TD) after long-term use.2 Perhaps clozapine’s most distinguishing features are that it has superior efficacy to typical and atypical antipsychotics in multiple studies and has been considered the “gold standard” for treatment for those with schizophrenia. Kane and colleagues’3 landmark study in 1988 demonstrated that nearly one-third (30%) of patients who failed to respond to haloperidol improved on clozapine, while 2 crucial prospective studies (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials for Interventions Effectiveness and Cost Utility of the Latest Antipsychotic Drugs in Schizophrenia Study4,5) substantiated clozapine’s superiority to other antipsychotics, including atypical agents, and subsequent studies (including meta-analyses) have consistently demonstrated that clozapine is superior to all other antipsychotics.2,6

Clozapine has also been associated with a reduction in suicide attempts, less suicidal behavior, and a decrease in suicide risk.6 Clozapine’s ability to affect neurotransmitters systems other than dopamine, such as serotonin and norepinephrine, may account for these observations. These findings led to clozapine’s unique US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for decreasing recurrent suicidal behavior in individuals with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.7

The use of clozapine is primarily limited by its side effect profile, particularly its potential to induce serious complications, such as agranulocytosis. Other adverse outcomes include weight gain, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, anticholinergic effects, seizures, myocarditis, QT prolongation, cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, GI hypomotility or obstruction, sedation, sialorrhea, and orthostatic hypotension. As compared to other atypical antipsychotic agents, clozapine conveys a higher risk of developing weight gain, hyperglycemia, and diabetes.7

Who Is Most Likely to Receive Clozapine?

Owing to clozapine’s potential for causing serious complications, patients with psychotic symptoms are more commonly started on other antipsychotic medications that have safer side effect profiles. The FDA first approved clozapine for treatment-resistant schizophrenia (ie, those with symptoms that lasted longer than 12 weeks, with at least moderate functional impairment, and 2 or more different antipsychotic trials lasting for at least 6 weeks at doses equivalent to 600 mg of chlorpromazine/day, with confirmation that at least 80% of prescribed doses were taken with adherence assessed by use of 2 sources [eg, pill counts, dispense review, patient/caregiver report] and antipsychotic plasma levels monitored at least once).8 Therefore, patients with this condition were more likely to receive clozapine therapy than were those with other psychiatric disorders. Clozapine is also indicated for individuals who suffer from schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, have recurrent suicidal behaviors, and are judged to be at chronic risk for re-experiencing suicidal behavior based on their history and symptoms.

Others who receive clozapine include patients who experience psychotic symptoms and who are susceptible to developing EPS from other antipsychotics, such as those with Parkinson disease or other disorders of basal ganglia function, or patients who have experienced significant TD due to use of other antipsychotics. Investigators have hypothesized that clozapine’s pharmacokinetic properties of having a lower affinity and rapid dissociation “fast-off” for dopamine D2 receptors in the striatum (as opposed to longer occupation by medications, such as haloperidol or chlorpromazine) enable clozapine to provide antipsychotic effects while maintaining a relatively low risk of worsening adverse motor symptoms.9

What Are the Most Serious Complications of Clozapine Therapy, and Why Do They Arise?

The most serious complications of clozapine therapy include severe neutropenia/agranulocytosis, myocarditis/ cardiomyopathy, seizures, neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), and GI hypomotility.

Severe neutropenia, defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) less than 500/mm3, can lead to serious infections and death. Therefore, prior to initiating clozapine treatment, a baseline ANC of at least 1,500/ mm3 is required for use in the general population, while an ANC of at least 1,000/mm3 is needed for those with documented benign ethnic neutropenia. Furthermore, the ANC is monitored weekly during the first 6 months of clozapine treatment, then every 2 weeks for the next 6 months, and then monthly thereafter if it remains ≥1,500/mm3. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis is an idiosyncratic phenomenon (not a dose-related effect) that typically occurs during the first 18 weeks of clozapine treatment; however, cases have been reported after 6 months of clozapine administration. No clear pathogenesis for clozapine-induced agranulocytosis has been established, although an immune-mediated hypothesis has been proposed.10

Clozapine-induced myocarditis, a rare but potentially fatal adverse event, typically occurs within the first few months of clozapine treatment, with cardiomyopathy presenting later during therapy. Symptoms are highly variable (eg, asymptomatic, having nonspecific signs [fever, chest pain, flu-like symptoms], having signs of heart failure); laboratory testing can demonstrate eosinophilia, elevated levels of C-reactive protein, increased troponin levels, electrocardiographic changes, and/or sinus tachycardia. This variability often makes it difficult for clinicians to diagnose clozapine-induced myocarditis. Nevertheless, early detection is crucial, and clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for adverse events in patients starting clozapine. Rapid titration of clozapine also appears to be a risk factor for the development of myocarditis. Although its pathogenesis is unclear, one hypothesis involves an acute hypersensitivity reaction, as autopsy reports have demonstrated eosinophilic infiltrates in the myocardium.11

Dose-dependent tonic-clonic seizures are the most common type of seizure associated with clozapine use. Other seizure types (eg, myoclonic, atonic, simple, complex partial, and absence) have also been reported.12 Higher doses of clozapine (ie, >600 mg/day) have been associated with an increased risk of seizure, although case reports have been linked with use of lower doses (eg, 200–300 mg/day). A history of a seizure disorder, concurrent use of drugs that lower the seizure threshold, rapid dose escalation, the total oral dose, and organic brain disorders are risk factors for clozapine-induced seizures.12 Therefore, a thorough medical history (including a review of all medications, central nervous system pathology, and alcohol use), as well as a slow titration of clozapine, is recommended. The precise mechanism by which clozapine lowers seizure threshold remains unclear.

All antipsychotic drugs, including clozapine, have been associated with the onset of NMS. Case reports of clozapine-induced NMS suggest that it has atypical features, including fewer EPS and a lower rise in creatine kinase levels.13 Most individuals who develop clozapine-induced NMS develop it within several weeks of initiating clozapine; however, some reports have indicated that symptoms may arise months or years into treatment. Symptoms of NMS include confusion/mental status changes, muscle rigidity (ie, “lead pipe” rigidity), autonomic dysfunction, high fever, diaphoresis, dysphagia, tremor, and laboratory evidence of muscle injury (ie, an elevated level of creatine phosphokinase). NMS can be life-threatening, and it requires immediate treatment. Although the underlying mechanism of NMS is complex, most experts agree that a marked and sudden reduction in central dopaminergic activity that results from D2 dopamine receptor blockade within the nigrostriatal, hypothalamic, and mesolimbic/cortical pathways helps to explain some of the clinical features of NMS.14

CIGH is common, and it can progress to severe and potentially life-threatening complications, which will be discussed in the following section. Prevention of constipation should be a goal for all patients receiving clozapine. Clozapine has strong anticholinergic and antiserotonergic effects with antagonism of M1 and M3 receptors and HT2, 5-HT3, 5-HT6, and 5-HT7 receptors, respectively. Muscarinic receptors provide autonomic regulation of the intestine, smooth muscle contraction, and intestinal transit.15 With antagonism, the lack of peristalsis inhibits movement of GI contents, which causes constipation and retention of gas and fluid, thereby contributing to fecal retention and possible megacolon or obstruction. It has also been suggested that antiserotonergic effects reduce bowel nociception, which leads to delayed reporting by patients and thereby to delayed diagnosis.15 In addition, reduced motility of GI contents can raise luminal pressures and contribute to reduced mucosal perfusion. The antiadrenergic effects of clozapine may also contribute to hypotension. Reduced perfusion can result in mucosal breakdown and lead to GI ischemia, necrosis, and/or perforation.15

Which GI-Related Signs and Symptoms Suggest a Serious Complication From Clozapine, and How Should They Be Evaluated?

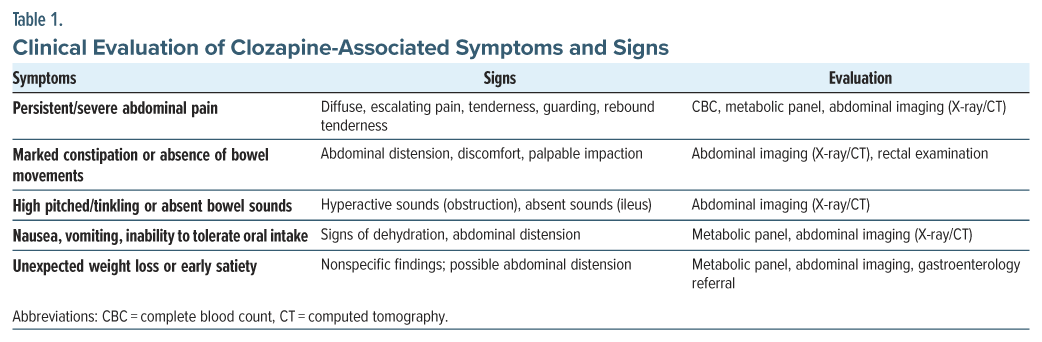

Constipation due to clozapine is more prevalent than constipation due to any other antipsychotic.16,17 Although mild constipation is common among patients taking clozapine, reported in as many as 30%–60% of clozapine-treated individuals—more serious complications, including intestinal pseudo-obstruction, paralytic ileus, and bowel perforation, also occur, albeit at a much lower rate.16–18 Therefore, primary care providers (PCPs) should maintain a heightened index of suspicion for severe GI problems in any patient receiving clozapine who presents with worsening, or atypical, GI symptoms. “Red flag” signs and symptoms that may signal a serious GI complication, along with the recommended evaluations, are summarized in Table 1. Given that these GI events may escalate rapidly, timely recognition and intervention is critical.

A systematic and stepwise approach into the assessment of GI signs and symptoms is advised. The components of the assessment should include obtaining a clinical history and reviewing the medications received, performing a physical examination, and ordering laboratory tests and imaging studies. It is wise to begin with a detailed history that emphasizes the time course and severity of symptoms, recent changes in bowel habits (eg, frequency, stool consistency), associated symptoms (eg, pain, bloating, nausea, or vomiting), and red flag features (eg, fever, severe pain, hematochezia, or melena). It is also essential to ascertain whether the patient has been, or is, taking other constipating medications (eg, anticholinergics, opioids) that could slow GI motility and facilitate bowel obstruction.18

A focused abdominal examination should include inspection for abdominal distension that may suggest ileus, auscultation for high-pitched/tinkling sounds (which can be heard in obstruction), or absent/reduced sounds (which may indicate ileus); palpation for tenderness, guarding, or rebound tenderness (which can help to identify potentially severe underlying pathology) is essential. Rectal examination may also be useful to assess for impacted stool. Basic laboratory assessments, including a complete blood count and metabolic panel, can help to identify electrolyte imbalances (eg, hypokalemia) that may worsen GI motility and to assess for infection or inflammation. These tests can also guide further management, while obtaining a clozapine blood level can inform choices about optimizing dosing and monitoring for correlates of GI side effects. Imaging studies (eg, a plain abdominal X-ray [upright and supine views]) may reveal patterns of dilated bowel loops, air-fluid levels suggestive of obstruction, or generalized air patterns consistent with an ileus, while an abdominal CT scan can detect perforation, severe pseudo-obstruction, providing a more detailed evaluation of the bowel lumen, wall integrity, and status of surrounding tissues. Abdominal ultrasounds, although not as commonly used for the assessment of obstruction in adults, may help, especially when radiation exposure is a concern for a patient (eg, a pregnant woman). In cases that are resistant to standard interventions or when structural abnormalities are suspected, referral for a gastroenterological evaluation and/or surgical evaluation is warranted; endoscopy—either sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy—may be considered to rule out mechanical obstruction or other mucosal lesions, although these procedures must be conducted with caution in the setting of severe abdominal distension or pseudo-obstruction (to avoid bowel perforation).

In summary, the evaluation of clozapine-associated GI symptoms involves a careful integration of clinical findings, targeted laboratory tests, and appropriate imaging procedures. Timely recognition and prompt assessment are crucial to prevent progression to more severe complications.

Which Patients Are at Especially High Risk for GI Complications?

Older adults, those with an underlying GI disorder, those on high clozapine doses, or who are taking other anticholinergic medications or opioids (that slow gut motility) appear to be at an increased risk for GI complications. However, serious CIGH can occur even when low doses are used. Unfortunately, there is no clear or consistent relationship between an individual’s age, the clozapine dose, the duration of use, or the serum clozapine level and GI complications.16

Lifestyle factors (eg, diet and exercise) also influence the incidence of constipation; however, the exact role of lifestyle factors on GI complications remains poorly understood, and it warrants further investigation.18 Regular inquiry about bowel habits and GI symptoms should be incorporated into routine follow-up visits for patients on clozapine. If constipation worsens or becomes refractory to standard treatments (eg, stool softeners, laxatives), further evaluation is warranted.16

Early identification of GI side effects and initiation of timely interventions (eg, lowering medication doses, modifying the timing and dosing of other constipating medications, or involving gastroenterology and/or the surgical service) may prevent the escalation of symptoms into GI/surgical emergencies.

Ultimately, PCPs play a pivotal role in the early recognition and initial management of clozapine-related GI complications. Remaining vigilant and screening for subtle changes in bowel habits will facilitate prompt investigation of suspicious symptoms and foster interdisciplinary communication to mitigate the risks associated with clozapine administration.

When, Why, and How Rapidly Should the Clozapine Dose/Blood Level Be Reduced to Minimize GI Signs and Symptoms or Dose Increased When Necessary?

Evidence suggests that the severity and persistence of GI side effects (including constipation, ileus, and pseudo-obstruction) should guide decisions to reduce or discontinue the clozapine dose.16,18 While mild constipation can frequently be managed with laxatives and dietary adjustments, more severe or refractory GI symptoms warrant closer attention and may necessitate modification of the dosing regimen.16,18

Reducing the dose or temporarily stopping clozapine should be considered when a patient presents with severe GI complications or fails to improve with conservative measures (eg, use of laxatives, increase in fluid/fiber intake). Red-flag symptoms that should prompt dose adjustments include having significant abdominal pain, pronounced abdominal distension, prolonged absence of bowel movements, or imaging findings that are suggestive of ileus or obstruction.16,18 Given that clozapine has a half-life of approximately 12 hours, noticeable improvements in GI symptoms usually develop within 1–2 days after a dose reduction or discontinuation. Therefore, clinicians should anticipate relatively quick improvement in GI symptoms, guiding further dosing adjustments and management strategies. Patients who are at higher risk of GI complications (eg, older adults, those taking other constipating medications, or individuals on high doses of clozapine) may benefit from earlier and more proactive interventions.16,18

In acute situations where ileus, pseudo-obstruction, or impending perforation is suspected, the clozapine dose should be reduced immediately or held until the patient becomes stable.16 For less severe but persistent symptoms, a stepwise dose reduction (eg, decreasing the total daily dose by 25%–50%) may alleviate GI signs and symptoms while allowing for careful monitoring of psychiatric stability. The pace of the dose reduction should be tailored to each patient, with more rapid adjustments made in cases of severe clinical deterioration. Close collaboration with psychiatric services is essential to ensure a workable balance between the prevention of psychotic relapse and the promotion of GI recovery.

Once a patient’s GI symptoms have resolved or substantially improved, cautious retitration of clozapine should be considered, while determining whether the psychiatric benefits outweigh the risks. Reinitiation of clozapine should proceed gradually, starting at a lower dose, supplemented by prophylactic GI measures (eg, stool softeners or promotility agents), if appropriate.18 Ongoing vigilance is critical: monitoring bowel habits, encouraging dietary modifications, and maintaining a low threshold for reintroducing GI interventions can help prevent recurrence of severe symptoms.16,18

Is It More Important to Lower the Clozapine Dose or Blood Level When Attempting to Mitigate the GI Signs and Symptoms?

When managing clozapine-related GI side effects, both the clozapine dose and serum concentration (clozapine blood level) are important considerations. However, evidence suggests that blood levels, which reflect the actual systemic exposure to the medication, may be more important than the absolute dose prescribed,16,19 because of individual pharmacokinetic differences, eg, variable metabolism through the cytochrome P450 system, which can lead to variability in drug blood levels even when used at comparable doses.19

While clinical experience and some psychiatric literature suggest that maintaining moderate plasma levels (eg, 350–450 ng/mL) may reduce severe GI side effects, debate remains regarding this matter. For instance, Shirazi and associates18 found no clear association between constipation risk and clozapine dose or plasma level. This discrepancy highlights the importance of individualized monitoring and underscores that plasma levels should be one of several clinical factors guiding dose adjustments.

When considering which initial intervention to make when a patient develops concerning GI symptoms, it is prudent to consider obtaining a clozapine trough level to assess the current exposure to clozapine.19 If clozapine levels are found to be substantially above the therapeutic range, a gradual dose reduction aimed at bringing the plasma level down to a safer target (often 350–450 ng/mL) can be undertaken. Improvements in GI function should also be monitored closely.

If psychiatric symptoms relapse upon dose reduction, clinicians may cautiously titrate the dose upward, while employing proactive GI measures (eg, laxatives, stool softeners, adequate hydration, and possibly prokinetic agents) to manage GI side effects. Any upward titration should be done slowly, with repeated checks of plasma levels and ongoing vigilance for the return of GI symptoms.

Ultimately, the goal is to maintain the lowest effective plasma clozapine concentration that achieves psychiatric stability, while minimizing GI risks. Regular communication among psychiatrists, PCPs, and gastroenterologists can ensure optimal management.

What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Clozapine Withdrawal?

Abrupt discontinuation of clozapine increases the risk of relapse with psychotic symptoms, particularly in those with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, a condition in which clozapine might be the only effective medication. Clozapine-associated withdrawal psychosis occurs in up to 20% of cases, with symptoms typically worsening within 7–14 days of the dose decrease.20 In addition, clozapine’s anticholinergic potency can lead to “cholinergic rebound” when the drug is discontinued abruptly, even when doses as low as 50 mg/day were used. This cholinergic rebound develops in up to half of clozapine-treated individuals, with symptoms that resemble those of delirium (eg, with agitation, disturbed sleep, hallucinations, confusion) as well as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, diaphoresis, and abnormal movements that mimic those of EPS.20 If clozapine must be discontinued abruptly, anticholinergic agents (eg, trihexyphenidyl, benztropine, biperiden) can be initiated to mitigate cholinergic rebound20; however, this increases the likelihood of GI-related issues, eg, constipation.21

Serotonin discontinuation syndrome has also been reported following clozapine cessation, from doses as low as 37.5 mg per day.20 Symptoms related to discontinuation of serotonergic agents typically appear within several days and appear to be related to clozapine’s function as a 5-HT2A antagonist, where its removal could lead to serotonin receptor super-sensitivity.20 Rarely, clozapine withdrawal-induced catatonia can also arise and may relate to clozapine’s ability to modulate γ- aminobutyric acid. Both benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy have been effective in the treatment of such cases.20

Given the above information, clozapine should be tapered gradually whenever possible; however, abrupt cessation is necessary in emergency situations (eg, in life-threatening situations such as acute bowel obstruction).

Which Medications Can Reduce GI Symptoms Associated With Clozapine Therapy?

Since clozapine-induced constipation is thought to result from its anticholinergic and antiserotonergic mechanisms,16 the negative consequences of CIGH can be reduced by using the lowest effective dose of clozapine whenever possible16 and by avoiding medications that reduce bowel motility (eg, anticholinergics, opiates, iron, calcium, and verapamil).22 Reducing the anticholinergic burden is critical to mitigating clozapine-induced constipation. The concurrent use of anticholinergic agents (eg, antihistamines, tricyclic antidepressants, antimuscarinics, muscle relaxants, and medications for overactive bladder or urinary incontinence, such as oxybutynin) should be reviewed carefully.22 Glycopyrrolate, commonly prescribed for clozapine-induced sialorrhea, can also contribute to constipation, especially when high doses are prescribed. Similarly, anticholinergic agents (eg, benztropine and trihexyphenidyl), which are frequently used for antipsychotic-induced EPS, can also exacerbate constipation. Procholinergic agents (eg, bethanechol, a cholinergic agonist for urinary retention, and donepezil, an anticholinesterase inhibitor for dementia) have been suggested to counteract the anticholinergic effects of clozapine.23,24 When a patient presents with distressing GI symptoms, consultation with a gastroenterologist is prudent.22

What Might the Bowel Regimen Entail for a Patient Receiving Clozapine?

Proactive prophylactic laxative use is strongly recommended for all patients on clozapine,25 especially in those with cognitive impairments (eg, individuals with intellectual disabilities or elderly persons with dementia), who may not be able to verbalize their needs or effectively utilize as-needed laxatives. In addition to encouraging increased fluid intake and physical activity, osmotic laxatives (like polyethylene glycol) are effective in promoting bowel movements, while stimulant laxatives (eg, senna or bisacodyl) activate bowel motility. Combination therapies (eg, a stool softener like docusate 100 mg twice daily) coprescribed with a stimulant laxative (weekly and as-needed doses of bisacodyl 5–15 mg/day or senna glycoside 15 mg/day) achieve a synergistic effect.26 The Porirua Protocol23 demonstrated that the combination of docusate and senna, augmented with polyethylene glycol, significantly improved GI transit time. It is crucial to avoid psyllium-based laxatives, as bulk-forming agents can exacerbate constipation in these individuals. For refractory cases, secretagogues (eg, lubiprostone or linaclotide), while not widely studied in clozapine-treated patients, have shown efficacy in some case reports.27,28

What Happened to Ms A?

Ms A was admitted for conservative management, including nasogastric decompression, intravenous fluids, electrolyte correction, and temporary discontinuation of clozapine. Olanzapine was discontinued to reduce its additional anticholinergic burden, and a prokinetic agent was introduced, along with an intensified bowel regimen. Her bowel function gradually improved, allowing for the cautious reintroduction of clozapine at a lower dose with close multidisciplinary monitoring. She was discharged with an optimized bowel regimen and follow-up care with her PCP, psychiatrist, and gastroenterologist.

CONCLUSION

Clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic, has been considered the gold standard for treatment for those with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, as it has superior efficacy to typical and atypical antipsychotics and reduces the number of suicide attempts. However, use of clozapine has been primarily limited by its side effect profile, particularly by its potential to induce serious complications such as agranulocytosis. Other adverse outcomes of clozapine include weight gain, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, anticholinergic effects, seizures, myocarditis, QT prolongation, cardiomyopathy, pancreatitis, GI hypomotility or obstruction, sedation, sialorrhea, NMS, and orthostatic hypotension. In addition, as compared to other atypical antipsychotic agents, clozapine and olanzapine convey a higher risk of developing weight gain, hyperglycemia, and diabetes.

The components of the GI assessment should include obtaining a clinical history that emphasizes the time course and severity of symptoms, recent changes in bowel habits, associated symptoms (eg, pain, bloating, nausea, or vomiting), and red flag features (eg, fever, severe pain, hematochezia, or melena) and reviewing the medications received, performing a physical examination, and ordering laboratory tests and imaging studies. It is also essential to ascertain whether the patient has been, and is, taking other constipating medications (eg, anticholinergics and opioids) that could slow GI motility and facilitate bowel obstruction.

Once a patient’s GI symptoms have resolved or substantially improved, cautious retitration of clozapine should be considered, while determining whether the psychiatric benefits outweigh the risks.

Article Information

Published Online: August 12, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03984

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: April 15, 2025; accepted May 5, 2025.

To Cite: Perez JH, Bains A, Lim CS, et al. Gastrointestinal complications of clozapine treatment: assessment and management. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025; 27(4):25f03984.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Perez, Bains, Lim, Stern); McLean Hospital, Belmont, Massachusetts (Perez); Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Perez, Bains, Lim, Stern); Clozapine Clinic, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Lim).

Perez, Bains, and Lim are co-first authors; Stern is senior author.

Corresponding Author: Carol Lim, MD, MPH, Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, 151 Merrimac St, 4th Floor, Boston, MA 02114 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal (GI) hypomotility is common, and it can progress to severe and potentially life-threatening complications.

- Primary care providers should maintain a heightened index of suspicion for severe GI problems in any patient receiving clozapine; prevention of constipation should be a goal for all patients receiving clozapine, which is a highly potent anticholinergic agent.

- Early identification of GI side effects and initiation of timely intervention may prevent the escalation of symptoms into GI/surgical emergencies.

- Imaging studies (eg, abdominal X-ray) may reveal patterns of dilated bowel loops, air-fluid levels suggestive of obstruction, or generalized air patterns consistent with an ileus, while an abdominal computed tomography scan can detect perforation, severe pseudo-obstruction, providing a more detailed evaluation of the bowel lumen, wall integrity, and status of surrounding tissues.

- Procholinergic agents (eg, bethanechol, a cholinergic agonist for urinary retention, and donepezil, an anticholinesterase inhibitor for dementia) have been suggested to counteract the anticholinergic effects of clozapine.

References (28)

- Hippius H. A historical perspective of clozapine. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 12):22–23. PubMed

- Nucifora FC Jr, Mihaljevic M, Lee BJ, et al. Clozapine as a model for antipsychotic development. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):750–761. PubMed CrossRef

- Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic: a double-blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45(9):789–796. PubMed CrossRef

- McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior atypical antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):600–610. PubMed CrossRef

- Lewis SW, Barnes TRE, Davies L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of effect of prescription of clozapine versus other second-generation antipsychotic drugs in resistant schizophrenia (CUtLASS 2). Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(4):715–723. PubMed CrossRef

- Khokhar JY, Henricks AM, Sullivan ED, et al. Unique effects of clozapine: a pharmacological perspective. Adv Pharmacol. 2018;82:137–162. PubMed CrossRef

- Schatzberg AF, DeBattista C. Antipsychotic drugs. In: Cole JO, DeBattista C, Schatzberg F, eds. Manual of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 8th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2015:223–233.

- Howes OD, McCutcheon R, Agid O, et al. Treatment-resistant schizophrenia: treatment response and resistance in psychosis (TRRIP) working group consensus guidelines on diagnosis and terminology. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(3):216–229. PubMed CrossRef

- Seeman P. Clozapine, a fast-off-D2 antipsychotic. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5(1): 24–29. PubMed CrossRef

- Mijovic A, MacCabe JH. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(11):2477–2482. PubMed CrossRef

- Kilian JG, Kerr K, Lawrence C, et al. Myocarditis and cardiomyopathy associated with clozapine. Lancet. 1999;354(9193):1841–1845. PubMed CrossRef

- Williams AM, Park SH. Seizure associated with clozapine: incidence, etiology, and management. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(2):101–111. PubMed CrossRef

- Sachdev P, Kruk J, Kneebone M, et al. Clozapine-induced neuroleptic malignant syndrome: review and report of new cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;15(5):365–371. PubMed CrossRef

- Berman BD. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a review for neuro-hospitalists. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(1):41–47. PubMed CrossRef

- West S, Rowbotham D, Xiong G, et al. Clozapine induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: a potentially life-threatening adverse event. A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;46:32–37. PubMed CrossRef

- Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM. Clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility: a 22- year bi-national pharmacovigilance study of serious or fatal ‘slow gut’ reactions, and comparison with international drug safety advice. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(8):699–709. PubMed CrossRef

- De Hert M, Correll CU, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry. 2011;10(1):52–77. PubMed CrossRef

- Shirazi A, Stubbs B, Gomez L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of clozapine- associated constipation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(6):863. PubMed CrossRef

- Nielsen J, Damkier P, Lublin H, et al. Optimizing clozapine treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(6):411–422. PubMed CrossRef

- Blackman G, Oloyede E, Horowitz M, et al. Reducing the risk of withdrawal symptoms and relapse following clozapine discontinuation—is it feasible to develop evidence-based guidelines? Schizophr Bull. 2022;48(1):176–189. PubMed CrossRef

- Bickerton L, Kuriakose JL. Management of cholinergic rebound after abrupt withdrawal of clozapine: a case report and systematic literature review. JACLP. 2024;65(1):76–88. PubMed CrossRef

- Edinoff AN, Sauce E, Ochoa CO, et al. Clozapine and constipation: a review of clinical considerations and treatment options. Psychiatry Int. 2021;2(3):344–352. CrossRef

- Every-Palmer S, Ellis PM, Nowitz M, et al. The Porirua protocol in the treatment of clozapine-induced gastrointestinal hypomotility and constipation: a pre-and post- treatment study. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(1):75–85. PubMed CrossRef

- Poetter CE, Stewart JT. Treatment of clozapine-induced constipation with bethanechol. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(5):713–714. PubMed CrossRef

- Attard A, Iles A, Attard S, et al. Clozapine: why wait to start a laxative? Br J Psych Adv. 2019;25(6):377–386. CrossRef

- Cruz A, Freudenreich O. Clozapine-induced GI hypomotility: from constipation to bowel obstruction. Curr Psychiatry. 2018;17(8):44–45.

- Torrico TJ, Kaur S, Dayal M, et al. Lubiprostone for the treatment of clozapine-induced constipation: a case series. Cureus. 2022;14(6):e25576. PubMed CrossRef

- Tomulescu S, Uittenhove K, Boukakiou R. Managing recurrent clozapine-induced constipation in a patient with resistant schizophrenia. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2021;2021(1):9649334. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!