Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25f03942

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you felt ill-prepared to know what to do and how quickly interventions need to be made when one of your patients develops priapism? Have you been uncertain about how long monitoring and treatment for priapism will be needed and which factors guide those decisions? Have you wondered why priapism develops and whether your patients can be rechallenged with the psychotropic medication that precipitated priapism? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr A, a 30-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder, presented to the emergency department for the third time in 2 weeks with a prolonged, painful erection of spontaneous onset. His current medications included long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate (administered every 4 weeks, with the most recent dose given 4 days prior), valproic acid (1,000 mg daily), and benztropine (1 mg twice daily). After the consulting urologist performed an aspiration and irrigated with phenylephrine, detumescence occurred. Priapism recurred twice more over the next several hours, each episode managed with another aspiration and irrigation. Mr A was then admitted for the management of recurrent ischemic priapism. His hematologic workup, which included sickle cell testing, was negative. Given Mr A’s recurrent priapism and his primary psychotic illness, the urology service recommended holding all psychotropics and consulting psychiatry for further recommendations.

His medication history was notable for previous trials of aripiprazole, haloperidol, and fluphenazine; each of which had been ineffective for his psychosis. Although olanzapine was initially beneficial, it was discontinued due to the development of priapism. After discussing the situation with Mr A’s outpatient psychiatry team, a trial of aripiprazole (10 mg daily) was recommended due to its lower affinity for α-1 adrenergic receptors. However, priapism recurred that evening, along with acute agitation. Mr A was again treated with penile irrigation and phenylephrine injection the following morning. Further deliberations about next steps were undertaken.

DISCUSSION

What Is Priapism?

Priapism is a rare but potentially serious medical condition characterized by a prolonged, persistent, and often painful erection of penile or clitoral tissue lasting at least 4 hours or occurring in the absence of sexual stimulation.1 Priapism is associated with a variety of medications, especially psychotropics (eg, antipsychotics and antidepressants), although the risk varies across different classes and agents. In those with a history of priapism or with conditions that predispose to hypercoagulability (eg, sickle cell disease), psychotropic medication selection should aim to mitigate this risk.

Although the precise mechanism of priapism remains incompletely understood, α-1 adrenergic blockade is believed to play a key role.

Priapism is divided into 2 types: nonischemic and acute ischemic. Nonischemic priapism (also known as high-flow priapism) results from uncontrolled high-flow arterial blood entering the penis, typically due to an injury to the genital or perineal region. This dysfunction in arterial flow and smooth muscle tone leads to prolonged erections that are generally painless and can last anywhere from hours to weeks. Nonischemic priapism is not considered a medical emergency, as it does not carry a high risk of permanent erectile dysfunction (ED). Ischemic priapism, however, is a low-flow state caused by venous outflow obstruction, leading to stagnant, deoxygenated blood trapped in the corpora cavernosa. This condition is acutely painful and constitutes a medical emergency due to the high risk of cavernosal fibrosis, which can lead to ED if left untreated.1 Smooth muscle edema and atrophy begin in as little as 6 hours; more than half of patients whose ischemic priapism persists beyond 24 hours have permanent ED.2 As such, initial emergent medical evaluation is crucial to distinguish between ischemic and nonischemic priapism and guide appropriate treatment. Acute ischemic priapism accounts for more than 95% of priapism episodes and has an incidence of 5.34 per 100,000 men.3,4 Causes of acute ischemic priapism include hematologic conditions (eg, sickle cell disease), malignancies, toxin-mediated reactions (eg, scorpion stings, spider bites, rabies), and several pharmacologic agents, although it is often idiopathic.5–7 Recurrent or stuttering priapism is a subtype of ischemic priapism featuring episodes of priapism that are separated by periods of detumescence.8 Recurrent priapism is especially common in individuals with sickle cell disease. In patients without sickle cell disease, recurrent priapism may commonly arise due to alterations in inflammation, cellular adhesion, nitric oxide metabolism, vascular reactivity, and androgen level regulation.7

How and When Should Acute Ischemic Priapism Be Treated?

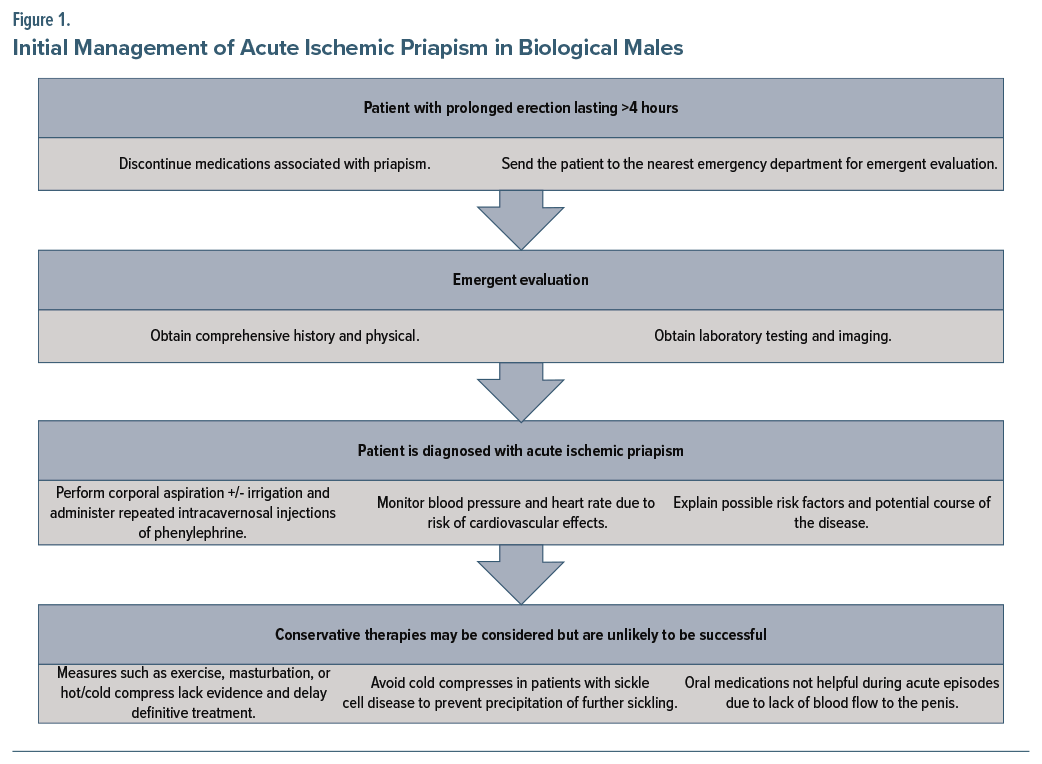

Because acute ischemic priapism is a urological emergency and can result in permanent ED, immediate diagnosis and definitive treatment are essential. The first step in the management of priapism is emergent evaluation in the emergency department. A comprehensive history should be obtained, covering the duration of the erection, the presence of pain, prior episodes of priapism and its treatment, the medical history (eg, hemoglobinopathies or hypercoagulable states), reports of trauma to the perineal region, home medications (including medications or supplements used for ED), and recreational substance use.7 The physical examination should include examination of the genitalia, perineum, and abdomen. Laboratory testing should include a complete blood count with a differential, a coagulation profile, and a corporal blood gas with penile ultrasound to differentiate between ischemic and nonischemic priapism.7 Medications that have been associated with priapism should be discontinued promptly. If the medications discontinued are psychotropics, psychiatry should be consulted for recommendations.

Treatment of acute ischemic priapism targets removing the trapped blood (ie, decompression of the corpora cavernosa via corporal penile aspiration until fresh, oxygenated blood appears and then administration of an intracavernosal injection of phenylephrine1) and restoration of normal circulation in rapid sequence. Phenylephrine constricts blood vessels, allowing blood to drain from the penis. Use of conservative strategies (eg, observation, exercise, cold compresses, masturbation, or oral medications) may be used concurrently with (but should not delay) definitive treatment, as they are unlikely to be successful and in some cases may be harmful.1 In those with sickle cell disease, for example, cold compresses can worsen the condition by inducing further sickling. Moreover, oral medications are unlikely to be beneficial during an acute episode of ischemic priapism due to lack of blood flow to the penis.1,9 Figure 1 depicts initial management of drug-induced ischemic priapism in biological males.

Clitoral priapism, although painful, is not a medical emergency, since there is a collateral blood supply to the clitoris that makes ischemia unlikely.10 Outflow obstruction due to urogenital malignancies has also been noted as a rare cause of clitoral priapism.11 Management includes stopping the offending agent and starting oral pseudoephedrine or imipramine in place of initial aspiration and irrigation.10 If oral agents are ineffective, intracavernosal injection of an α agonist can be considered.10

Which Medications Are Most Likely to Cause Ischemic Priapism?

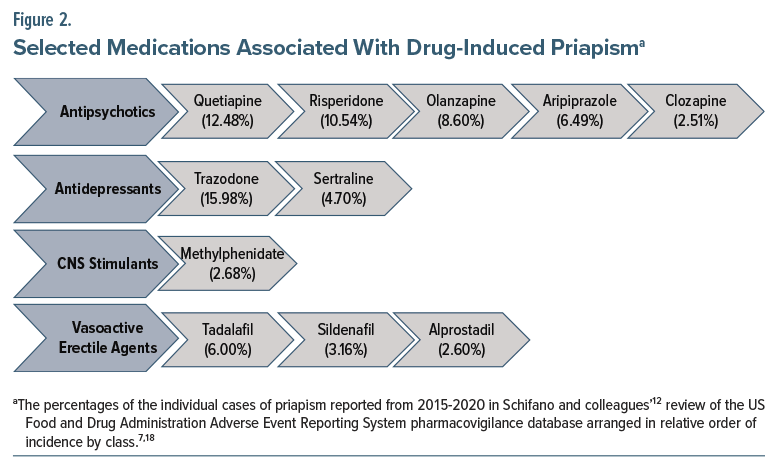

Although ischemic priapism is most often idiopathic, drug-induced priapism due to antidepressants, antipsychotics, anxiolytics, anticoagulants, antihypertensives, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, intracavernosal injections of erectogenic medications, and recreational substances (such as cocaine, cannabis, and alcohol)7 accounts for approximately 25%–40% of cases.8 While rare, drug-induced priapism tends to occur at the onset of treatment, although no definitive associations with dosage or treatment duration have been established. Given the rarity of this adverse effect, data on its incidence and prevalence by specific agent and dosage are limited. Polypharmacy involving medications that affect blood flow, smooth muscle function, neurotransmitter concentration, or that have α-blocking properties may increase cumulative risk and warrant caution. A review of reported adverse drug events from 2015 to 2020 found that roughly three-fourths (76%) of cases of drug-induced priapism were associated with just 11 medications, listed here in order of decreasing frequency: trazodone, quetiapine,risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, tadalafil, sertraline, sildenafil, methylphenidate, alprostadil, and clozapine.12

Trazodone, a serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI), is the most common cause of drug-induced priapism, accounting for 15.98% of reported cases.12 Despite its association with priapism, trazodone remains widely prescribed, ranking 18th among all medications prescribed in the United States in 2022, with over 27 million prescriptions dispensed to nearly 6 million patients.13 The incidence of trazodone-induced priapism in biological males is estimated to occur in less than 1% of patients with an incidence between 1 in 1,000 and 1 in 10,000, with most cases occurring within 1 month of initiation.14–16 Despite being the most frequently reported to the US Food and Drug Administration, trazodone-associated priapism accounted for just 197 individual cases.12 Sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressant and the most prescribed medication on this list (11th most prescribed in the United States in 2022 with nearly 40 million prescriptions for 8 million patients), is noted to have priapism occur in <2% of patients.13,17

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) represented 4 of the top 5 most frequently implicated agents in drug-induced priapism.12,18 Antipsychotics as a class are responsible for an estimated one-third to one-half of drug-induced priapism cases, most commonly affecting men under the age of 40.6,7,18 Similar to trazodone, priapism associated with antipsychotics may occur upon treatment initiation, reinitiation, or when switching agents.12 In the 2015–2020 review of adverse drug events, the number of reported priapism cases associated with individual antipsychotics ranged from 31 to 153: quetiapine (153), risperidone (130), olanzapine (106), aripiprazole (80), and clozapine (31).12 Risperidone, a dopamine and serotonin receptor antagonist with mild α-adrenergic activity, is one of the most frequently implicated among SGAs, especially at higher doses or with rapid titrations.19–22

Although trazodone and sertraline are prescribed more frequently than any single antipsychotic, antipsychotics as a drug class appear more likely to cause priapism than antidepressants. However, meaningful comparisons are limited by the overall rarity of the condition, potential underreporting, and variability in prescribing patterns. For example, the increased use of SGAs for off-label indications may contribute to a higher number of priapism reports. Conversely, the declining use of first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) has corresponded with fewer reported cases. Among FGAs, agents such as thioridazine, chlorpromazine, and haloperidol have been linked to priapism, though reports are less frequent today compared to SGAs. The relatively high number of cases involving aripiprazole, often prescribed first due to a favorable metabolic side effect profile, may reflect increased prescribing rather than a true higher risk. Similarly, the observed frequency of clozapine-induced priapism may increase following the recent removal of mandated clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) reporting requirements, which may have previously led to underprescribing and, therefore, underreporting.

Priapism has also been reported rarely following intracavernosal injections of erectogenic agents (eg, alprostadil for ED, especially when it is administered incorrectly or in high doses) at a rate of about 0.4%.4,23,24 Phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE-5) inhibitors (eg, sildenafil and tadalafil), oral medications primarily used to treat ED, are not considered independent risk factors for priapism unless they are taken in excess or in combination with other medications that affect smooth muscle and blood flow in the penis used to treat conditions such as benign prostatic hyperplasia or hypertension (eg, α-adrenergic antagonists like tamsulosin, prazosin, and doxazosin). Figure 2 outlines a selection of medications associated with increased risk of drug-induced priapism, while Supplementary Appendix A provides a comprehensive list of medications, recreational substances, and supplements linked to drug-induced priapism.

How Do Medications, Recreational Substances, or Supplements Cause Priapism?

Drug-induced priapism results from disruption of the normal regulation of blood flow, autonomic nervous system balance, or neurotransmitter concentration. Many medications, recreational substances, and supplements contribute to this dysregulation by promoting vasodilation and shifting autonomic tone toward increased parasympathetic activity. A key mechanism involves α-1 receptor blockade, which interferes with the sympathetic regulation responsible for detumescence of penile or clitoral tissue.25

Antidepressants, particularly SSRIs, may induce priapism through a combination of α-1 receptor antagonism, elevated peripheral serotonin levels, and altered autonomic tone. While most SSRIs have low affinity for α-1 receptors, sertraline has relatively higher α-1 affinity and has been associated with priapism.26 Trazodone, a SARI, has potent α-1–blocking effects and increases peripheral serotonin concentration, both of which contribute to inappropriate vasodilation. The risk is heightened when antidepressants are combined with other agents that also affect vascular tone (eg, PDE-5 inhibitors, α-1 blockers, or antipsychotics).

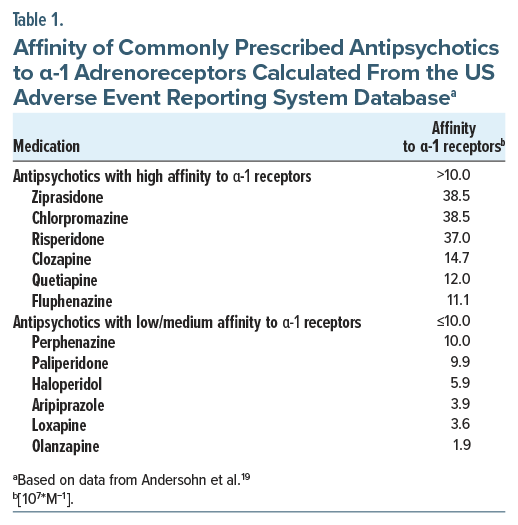

The exact pathophysiology of antipsychotic-induced priapism remains incompletely understood, but α-adrenergic blockade and changes in neurotransmitter concentrations in the corpora cavernosa are believed to play central roles.18 SGAs, such as quetiapine and risperidone, are more commonly implicated due to their stronger α-1 receptor antagonism.16,19 However, exceptions exist. Aripiprazole and olanzapine, both associated with priapism, have relatively low affinity for α 1-receptors. Aripiprazole’s antagonism of D2 receptors and 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A receptors may interfere with pathways that control vascular smooth muscle function, contributing to impaired detumescence. Interestingly, ziprasidone, an SGA with the highest α-1 affinity, is rarely reported in the literature. The rising incidence of priapism with SGAs may correlate with the increased use of antipsychotics for nonpsychotic or off-label indications. Table 1 outlines the relative α-1 affinities of antipsychotics.

A range of other agents (eg, α-adrenergic blockers, recreational drugs, and certain supplements) can cause priapism, particularly when used in combination or in high doses. PDE-5 inhibitors (eg, sildenafil, tadalafil) rarely cause priapism when used as prescribed. However, risk increases when these agents are used recreationally or combined with other vasodilators.18 Intracavernosal injections (eg, alprostadil) used to treat ED have a higher association with priapism, contributing to up to 7% of ischemic priapism cases.18 Alpha-1 adrenergic blockers (eg, tamsulosin, prazosin, doxazosin), often prescribed for benign prostatic hyperplasia or hypertension, relax vascular smooth muscle and may promote excessive penile blood flow while hindering venous drainage. Cocaine and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) increase peripheral serotonin concentrations and induce potent vasodilation, impairing venous outflow from the penis.27,28 Cannabis may promote priapism though a combination of sympathetic inhibition, increased parasympathetic tone, and direct cannabinoid effects on vasculature.28,29 Certain supplements, such as ginseng and horny goat weed, are marketed to increase sexual performance by improving blood flow through promoting nitric oxide production.30

How Should Clinicians Manage Recurrent Ischemic Priapism?

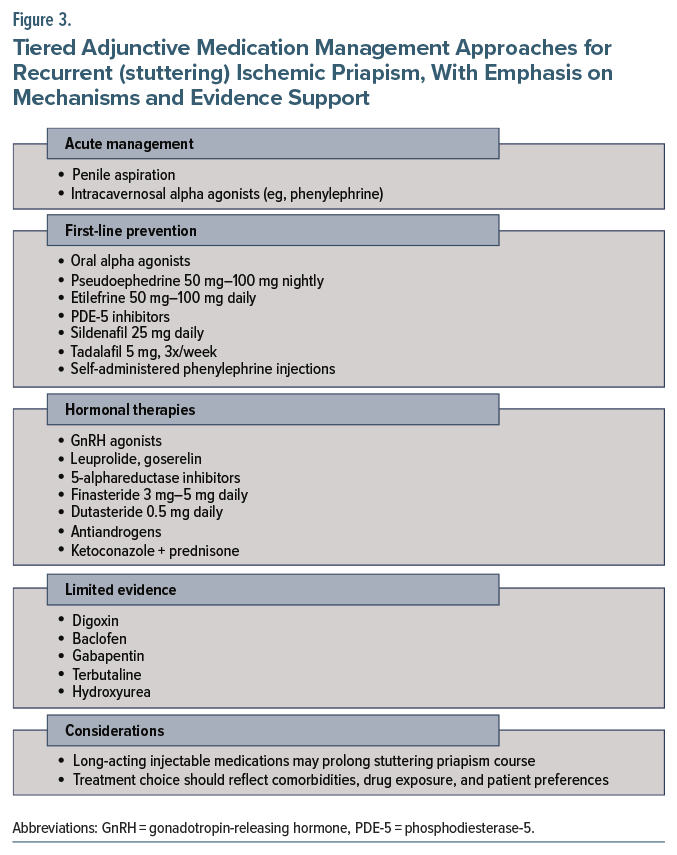

Management of acute episodes of recurrent (or stuttering) priapism is similar to that of standard acute ischemic priapism and includes penile aspiration and intracavernosal injection of α-adrenergic agonists, though adjunctive medications are often utilized to prevent further episodes.1,7 Most available evidence for managing stuttering priapism comes from studies involving individuals with sickle cell disease, as up to 30%–45% of adult males experience recurrent episodes, though clinical guidelines remain limited.31,32 After diagnosing recurrent priapism, preventative therapy should be tailored through shared decision-making, weighing risks, benefits, and side effects and considering the patient’s history and values.32

First-line preventative therapies. Initial pharmacologic management includes oral α-adrenergic agonists, self-administered intracavernosal α agonists, or PDE-5 inhibitors.33 Oral α agonists are effective in nearly three-fourths (72%) of cases of recurrent priapism.7 Options include pseudoephedrine (50 mg–100 mg nightly) and etilefrine (50 mg–100 mg once or twice daily).1,7,34 Intracavernosal α agonists, such as phenylephrine, may also be self-administered by patients at home. Low-dose PDE-5 inhibitors (eg, sildenafil 25 mg daily, tadalafil 5 mg 3 times weekly) are paradoxically effective in preventing priapism episodes. These agents promote tachyphylaxis, prevent downregulation of PDE-5, and prevent the degradation of cGMP, which is particularly beneficial in idiopathic and sickle cell–associated priapism.1,7,35

Hormonal therapies. Hormonal interventions aim to decrease central and/or peripheral testosterone levels to reduce androgen-driven priapism episodes and are generally reserved for adults who have failed first-line treatments. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists (eg, leuprolide acetate, goserelin acetate) suppress testosterone production centrally through downregulation of the pituitary gland. These medications are used in refractory cases due to their significant side effect burden. 5-α reductase inhibitors (eg, finasteride 3–5 mg daily, dutasteride 0.5 mg daily) block the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone and have been shown to reduce priapism episodes in individuals with sickle cell disease.33,36 Antiandrogens (eg, flutamide, bicalutamide, chlormadinone) suppress penile androgen receptor activity and are less likely to cause libido loss compared to GnRH agonists.37–39 Ketoconazole, an antifungal agent that reduces androgen production, is sometimes combined with prednisone for recurrent priapism (ketoconazole 200 mg 3 times daily plus prednisone 5 mg daily for 2 weeks, followed by ketoconazole 200 mg nightly for 6 months) but requires monitoring for hepatotoxicity.40 Hormonal therapies should not be used in patients who have not yet reached sexual maturity. In adults, side effects may include hot flashes, gynecomastia, ED, loss of libido, and infertility.

Other agents with limited evidence. Several additional medications have been explored with limited clinical data. Digoxin, a cardiac glycoside, may affect corporal smooth muscle relaxation by blocking the Na+/K+ pump, resulting in fewer hospitalizations for priapism and higher life satisfaction.1,35 Gabapentin is a γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) derivative that blocks voltage-gated calcium channels and reduces smooth muscle tone in the corpora cavernosa, leading to a decrease of testosterone and follicle-stimulating hormone levels.41,42 A case series showed that 400 mg 4 times daily, up to 2,400 mg daily, allowed 2 patients to remain symptom free for 16–24 months.43 Baclofen, a GABA-B receptor agonist and skeletal muscle relaxant, reduces erection and ejaculation via central inhibition (10 mg 1–3 times daily with weekly increases to a maximum of 90 mg daily).44 Terbutaline, a β-2 agonist, causes smooth muscle relaxation and may be particularly useful for priapism resulting from intracavernosal injections.45,46 When priapism recurs, 5–10 mg can be taken immediately followed by another 5 mg taken 15 minutes later, with 5–10 mg daily thereafter.31 Hydroxyurea, a chemotherapeutic agent used in sickle cell disease, prevents nitric oxide sequestration and may reduce priapism episodes through treatment of sickle cell disease.

Considerations in clinical decision-making. When initiating oral pharmacotherapy for recurrent priapism, clinicians should consider the suspected etiology, the indication for the medication in question, the patient’s history of priapism and prior effective treatments, and the half-life of any potentially offending medications. In patients with sickle cell disease, hydration status plays a critical role in the management of stuttering priapism; however, there is no evidence to support routine rehydration in patients without sickle cell disease (though the risk of adverse effects from rehydration is minimal). In most cases of drug-induced priapism, the causative agent is discontinued promptly, and patients typically do well. In patients receiving long-acting injectable antipsychotics, however, symptoms may persist until drug levels decline, which may take several days. In these scenarios, monitoring and a preventative strategy are warranted, along with consideration of alternative agents. Currently, there are no standardized guidelines for how long to monitor such patients based on drug half-life before discharge or discontinuation of adjunctive treatment. Preventative therapy should be guided by clinical judgement, prior efficacy, frequency of recurrence, and patient values. Figure 3 summarizes management strategies for recurrent ischemic priapism. Additional treatment details are provided in Supplementary Appendix B.

How Can Clinicians Select a Medication in the Context of Antipsychotic-Induced Priapism and Decompensated Psychotic Illness?

Although data guiding antipsychotic selection in patients with a history of priapism are extremely limited, clinicians must consider polypharmacy, the risk of priapism alongside psychiatric severity, medical and medication history, and patient preferences when making treatment decisions. Reducing polypharmacy is a key first step. The concomitant use of antipsychotics with α blockers, psychoactive substances, or medications for ED may increase the risk of priapism. For instance, in a patient with a primary psychotic disorder who is also receiving an α antagonist for hypertension, recurrent priapism should prompt consideration of an alternative antihypertensive agent. At the same time, dose reduction of the antipsychotic should be explored. If priapism persists despite dose reduction, switching to an antipsychotic with lower α-1 receptor affinity is recommended.19

Alpha-1 receptor affinity plays an important role in priapism risk. Mesoridazine, ziprasidone, and chlorpromazine have the highest α-1 receptor affinities, while loxapine, olanzapine, and pimozide exhibit the lowest.16,19 The physiologic picture is murky, however, as quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine, and aripiprazole are most frequently associated with priapism despite olanzapine and aripiprazole having relatively low α-blocking activity (Table 1). Clozapine affects multiple neurotransmitter systems including dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine and has significant α-adrenergic blocking activity. Conversely, ziprasidone, despite high α affinity, is more rarely reported to cause priapism than other agents. Despite comparatively low reported cases of loxapine- and ziprasidone-induced priapism in the literature among commercially available antipsychotics in the United States, these medications are prescribed much less commonly than other agents. Given the multifactorial neurochemical involvement, including dopaminergic, serotonergic, noradrenergic, and GABAergic pathways, clinical decisions need not rely solely on α-receptor–binding profiles, which explains the wide variety of potentially effective adjunctive agents (Figure 3).

While hormonal therapies are the most effective at preventing future occurrences, they often carry significant side effects that are typically troublesome for young patients. Agents such as gabapentin, baclofen, pseudoephedrine, or PDE-5 inhibitors may offer more favorable side effect profiles, and selection can be tailored to the patient’s psychotropic regimen. Deciding whether to restart or continue high-risk medications after an episode of priapism remains a major clinical challenge, especially in the absence of standardized guidelines. When considering reinitiating a high-risk medication, clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits of restarting versus withholding the agent, evaluate the potential role of adjunctive or preventative therapy, engage in shared decision-making with the patient, and clearly document the rationale and discussion in the medical record.

What Happened to Mr A?

Given the concern that Mr A’s medications were contributing to increased α-1 blockade and potentially worsening recurrent priapism, aripiprazole, hydroxyzine, valproic acid, and benztropine were discontinued. The psychiatrist started gabapentin at 400 mg 4 times daily, both as adjunctive treatment for stuttering priapism and off label use for anxiety. Despite these adjustments, Mr A remained agitated on day 5 of the hospital stay, which was characterized by near-constant internal preoccupation; therefore, parenteral haloperidol was administered along with lorazepam. Urology recommended a transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of a possible shunt. While awaiting discharge, Mr A required 1 additional corporal irrigation and phenylephrine injection. At the tertiary care center, recurrence of priapism did not occur for 48 hours, and Mr A requested a discharge home. The consultation-liaison psychiatry service restarted valproic acid at 500 mg daily and recommended close follow-up care by his outpatient team to consider restarting antipsychotic treatment.

CONCLUSION

Drug-induced priapism is a serious adverse reaction in those who have been prescribed antipsychotics and antidepressants. Data guiding antipsychotic selection in the setting of recurrent priapism are limited and guided primarily by medication efficacy and patient tolerability, as antipsychotics with relatively low α-1–blocking activity still report this side effect. Patients with recurrent drug-induced priapism who require long-term antipsychotic therapy necessitate psychiatry and urology comanagement, with likely use of adjunctive medications (eg, gabapentin, baclofen, or pseudoephedrine). Interventions prior to penile shunt (such as adjunctive medications) should be carefully considered to avoid permanent sexual dysfunction.

Article Information

Published Online: July 31, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03942

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: February 17, 2025; accepted April 22, 2025.

To Cite: DeSimone AC, Rudinoff E, Lee MY, et al. Psychotropic medication–induced priapism: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(4):25f03942.

Author Affiliations: Bayhealth Medical Center, Dover, Delaware (DeSimone, Zaragoza); Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (DeSimone, Zaragoza); Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (DeSimone, Zaragoza); Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina (Rudinoff); Jefferson Einstein Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Lee); Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire (Rustad); Larner College of Medicine at University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad); Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Stern).

Corresponding Author: Andrea C. DeSimone, DO, Bayhealth Medical Center, 640 S State St, Dover, DE 19901 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Drs DeSimone, Rudinoff, Lee, and Zaragoza have no disclosures to report. Dr Rustad is employed by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this presentation do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry.

Funding/Support: None.

Supplementary Material: Available at Psychiatrist.com.

Clinical Points

- Priapism is a rare but serious side effect associated with a variety of medications, particularly psychotropics; both antipsychotics and antidepressants have been linked to medication-induced priapism, with the risk varying across different classes and agents.

- In patients with a history of priapism or conditions that predispose to hypercoagulability (eg, sickle cell disease), careful selection of psychotropic medications becomes crucial to mitigate the risk of priapism.

- Informed consent should be provided for patients (involving discussion of the risk/benefit profile) before use of a psychotropic medication associated with priapism, and this discussion should be documented in the medical record.

- Treatment of priapism is often challenging for physicians and debilitating for patients (ie, painful and can result in permanent loss of sexual function).

References (46)

- Diagnosis and Management of Priapism: AUA/SMSNA Guideline. American Urological Association [Internet]. 2022. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines-and-quality/guidelines/diagnosis-and-management-of-priapism-aua/smsna-guideline-(2022)

- Zacharakis E, Raheem AA, Freeman A, et al. The efficacy of the T-shunt procedure and intracavernous tunneling (snake maneuver) for refractory ischemic priapism. J Urol. 2014;191(1):164–168. PubMed CrossRef

- Roghmann F, Becker A, Sammon JD, et al. Incidence of priapism in emergency departments in the United States. J Urol. 2013;190(4):1275–1280. PubMed CrossRef

- Broderick GA, Kadioglu A, Bivalacqua TJ, et al. Priapism: pathogenesis, epidemiology, and management. J Sex Med. 2010;7(1 Pt 2):476–500. PubMed CrossRef

- Baños JE, Bosch F, Farré M. Drug-induced priapism. Its aetiology, incidence and treatment. Med Toxicol Adverse Drug Exp. 1989;4(1):46–58.

- Hwang T, Shah T, Sadeghi-Nejad H. A review of antipsychotics and priapism. Sex Med Rev. 2021;9(3):464–471. PubMed CrossRef

- Salonia A, Bettocchi C, Capogrosso P, et al. EAU guidelines on sexual and reproductive health [Internet]. Eur Assoc Urology. 2024. https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-Guidelines-on-Sexual-and-Reproductive-Health-2024_2024-05-23-101205_nmbi.pdf

- Mansour E, Danaf S, Ghousayneh D, et al. Zuclopenthixol-induced ischemic priapism: case report and review of literature. J Fam Reprod Health. 2023;17(2):109–112. PubMed CrossRef

- Habous M, Elkhouly M, Abdelwahab O, et al. Noninvasive treatments for iatrogenic priapism: do they really work? A prospective multicenter study. Urol Ann. 2016;8(2):193–196. PubMed CrossRef

- Unger CA, Walters MD. Female clitoral priapism: an over-the-counter option for management. J Sex Med. 2014;11(9):2354–2356. PubMed CrossRef

- Schneiter MK, Stany MP. Clitoral priapism due to distant clitoral metastasis of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma: a case report and review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2018;24:99–101. PubMed CrossRef

- Schifano N, Capogrosso P, Boeri L, et al. Medications mostly associated with priapism events: assessment of the 2015-2020 Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pharmacovigilance database entries. Int J Impot Res. 2024;36(1):50–54. PubMed CrossRef

- ClinCalc DrugStats Database The Top 200 Drugs of 2022 [Internet]. 2022. https://clincalc.com/Drugstats/

- Shah T, Deolanker J, Luu T, et al. Pretreatment screening and counseling on prolonged erections for patients prescribed trazodone. Investig Clin Urol. 2021;62(1):85–89. PubMed CrossRef

- Sinkeviciute I, Kroken RA, Johnsen E. Priapism in antipsychotic drug use: a rare but important side effect. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2012;2012:496364. PubMed CrossRef

- Eisenach C, Lynch S. Trazodone-induced priapism and increased recurrence risk with antipsychotics. Am J Psychiatry Resid J. 2023;19(1):16–19. CrossRef

- UpToDate. Sertraline: Drug Information. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/sertraline-drug-information?search=sertraline&source=panel_search_result&selectedTitle=2%7E143&usage_type=panel&kp_tab=drug_general&display_rank=1#F220689

- Moodley D, Badenhorst A, Choonara Y, et al. The assessment and aetiology of drug-induced ischaemic priapism. Int J Impot Res. 2024.

- Andersohn F, Schmedt N, Weinmann S, et al. Priapism associated with antipsychotics: role of alpha1 adrenoceptor affinity. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(1):68–71. PubMed CrossRef

- Misawa F, Takeuchi H. Priapism and second-generation antipsychotics: disproportionality analysis of a spontaneous reporting system database in Japan. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2022;76(10):525–526. PubMed CrossRef

- Ateb S, Fourati T, Ben Rejeb H, et al. Risperidone-induced priapism: a case report and literature review. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2022;12:20451253221113246. PubMed CrossRef

- Refai S, Nakama HH. A case of priapism associated with rapid increase in risperidone dose. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(5):PCC.12l01365.

- Kunas G, Smereck J, Ladkany D, et al. Pharmacologically-induced recreational priapism: case report and review. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2020;4(4):591–594. PubMed CrossRef

- UpToDate. Alprostadil: Drug Information. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/alprostadil-drug-information?source=auto_suggest&selectedTitle=1∼1—1∼4—alprosta&search=alprostadil#F132136

- Scherzer ND, Reddy AG, Le TV, et al. Unintended consequences: a review of pharmacologically-induced priapism. Sex Med Rev. 2019;7(2):283–292. PubMed CrossRef

- Haberfellner EM. Priapism with sertraline-risperidone combination. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2007;40(1):44–45. PubMed CrossRef

- Altez-Fernandez C, Lamas L, Bohorquez M, et al. Cocaine-related ischemic priapism. Systematic review and presentation of a single center series. Actas Urol Esp Ed. 2024;48(4):281–288. PubMed CrossRef

- Tran QT, Wallace RA, Sim EHA. Priapism, ecstasy, and marijuana: is there a connection? Adv Urol. 2008;2008:193694. PubMed CrossRef

- Montgomery S, Sirju K, Bear J, et al. Recurrent priapism in the setting of cannabis use. J Cannabis Res. 2020;2(1):7. PubMed CrossRef

- Miocinovic R, Zafar S, Sferra J, et al. Priapism caused by “All Nite Long”. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(5):469–470. PubMed CrossRef

- Abdeen BM, Leslie SW. Stuttering priapism. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574517/

- Hammad MAM, Soltanzadeh Zarandi S, Barham DW, et al. Update on treatment options for stuttering priapism. Curr Sex Health Rep. 2022;14(4):140–149. CrossRef

- Yarak N, El Khoury J, Coloby P, et al. Idiopathic recurrent ischemic priapism: a review of current literature and an algorithmic approach to evaluation and management. Basic Clin Androl. 2024;34(1):21. PubMed CrossRef

- Okpala I, Westerdale N, Jegede T, et al. Etilefrine for the prevention of priapism in adult sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol. 2002;118(3):918–921. PubMed CrossRef

- Levey HR, Kutlu O, Bivalacqua TJ. Medical management of ischemic stuttering priapism: a contemporary review of the literature. Asian J Androl. 2012;14(1):156–163. PubMed CrossRef

- Rachid-Filho D, Cavalcanti AG, Favorito LA, et al. Treatment of recurrent priapism in sickle cell anemia with finasteride: a new approach. Urology. 2009;74(5):1054–1057. PubMed CrossRef

- Costabile RA. Successful treatment of stutter priapism with an antiandrogen. Tech Urol. 1998;4(3):167–168. PubMed

- Dahm P, Rao DS, Donatucci CF. Antiandrogens in the treatment of priapism. Urology. 2002;59(1):138. PubMed CrossRef

- Yamashita N, Hisasue S, Kato R, et al. Idiopathic stuttering priapism: recovery of detumescence mechanism with temporal use of antiandrogen. Urology. 2004;63(6):1182–1184. PubMed CrossRef

- Hoeh MP, Levine LA. Prevention of recurrent ischemic priapism with ketoconazole: evolution of a treatment protocol and patient outcomes. J Sex Med. 2014;11(1):197–204. PubMed CrossRef

- Yuan J, DeSouza R, Westney OL, et al. Insights of priapism mechanism and rationale treatment for recurrent priapism. Asian J Androl. 2008;10(1):88–101. PubMed CrossRef

- Daoud AS, Bataineh H, Otoom S, et al. The effect of vigabatrin, lamotrigine and gabapentin on the fertility, weights, sex hormones and biochemical profiles of male rats. Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2004;25(3):178–183. PubMed

- Perimenis P, Athanasopoulos A, Papathanasopoulos P, et al. Gabapentin in the management of the recurrent, refractory, idiopathic priapism. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(1):84–85. PubMed CrossRef

- Silberman M, Stormont G, Leslie SW, et al. Priapism. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2025. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459178/

- Lowe FC, Jarow JP. Placebo-controlled study of oral terbutaline and pseudoephedrine in management of prostaglandin E1-induced prolonged erections. Urology. 1993;42(1):51–54. PubMed CrossRef

- Priyadarshi S. Oral terbutaline in the management of pharmacologically induced prolonged erection. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(5):424–426. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!