Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04031

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever wondered how inpatients use technology to circumvent physicians’ orders (eg, dietary restrictions)? Have you been unsure about how to manage patients who bend or break hospital rules? Have you ever wondered how patient-owned handheld technology can interfere with shared decision-making? If you have, the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr A, a 63-year-old man who had worked odd jobs until being placed on disability due to heart failure approximately 25 years previously, had coronary artery disease, heart failure (with a moderately reduced ejection fraction), chronic kidney disease, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, morbid obesity, and posttraumatic stress disorder. He presented to an outside hospital with shortness of breath and was subsequently transferred to our academic medical center after pulmonary edema was diagnosed. This was Mr A’s fourth hospital admission within the past year for heart failure and/or pulmonary edema. He had been having difficulty accessing primary care due to mobility issues.

Psychiatry was consulted to evaluate and manage his irritability and intermittent refusal to take his medications (olanzapine 2.5 mg twice/d, bupropion 150 mg/d, and buspirone 5 mg 3 times/d) and to abide by dietary recommendations. Mr A noted that he had been irritable and was challenged by his repeated hospitalizations, having spent much of the past year in hospitals. He abhorred feeling “cooped up” and struggled with having limitations placed on him by hospital staff, which he believed was related to having had traumatic experiences. The psychiatry team recommended increasing his total olanzapine dose, while consolidating his regimen to olanzapine 5 mg twice/d, increasing his bupropion dose to 300 mg/d, and discontinuing buspirone.

Mr A was placed on a diabetes carbohydrate control diet with fluid restriction. However, he often demanded water, ice chips, and ice cream. He repeatedly ordered potato chips and other salty snacks from Amazon, which were delivered directly to his room.

DISCUSSION

Why Don’t Patients Follow Their Physicians’ Treatment Recommendations?

Although treatment nonadherence is typically conceptualized as a phenomenon of outpatient treatment, it should be considered in inpatient settings as well. While there is a paucity of literature describing how often patients fail to follow treatment recommendations in inpatient settings, this may underestimate how frequently these behaviors occur.

Patients choose not to follow treatment recommendations for myriad reasons, and it is important for clinicians to understand and anticipate common scenarios. For instance, patients may not have been told about the recommended treatments and thus may be unaware that they are not following them. In other instances where treatment recommendations have been communicated, patients may neither understand nor agree with the recommendations. Furthermore, patients may prioritize other aspects of care (eg autonomy, lifestyle) or feel unable to follow recommendations due to functional or logistical concerns. Finally, the meaning of illness for each patient should be understood to guide interventions. In inpatient settings where patients often feel vulnerable, patients may not follow treatment recommendations due to anger or frustration at their situation, condition, or health care team.

In addition to not following treatment recommendations, patients in inpatient settings can undermine treatment recommendations in other ways. Patients may minimize or obscure nonadherent actions, both of which may make it difficult for treatment teams to address nonadherence. Patients may also circumvent some recommendations, such as diet orders. Modern technologies, such as cell phone applications, make this easier to accomplish in inpatient settings.

Why Might Cell Phone Use Be Restricted in the Hospital?

Exchanging information and communicating effectively are key components of the patient-provider relationship. However, these relationships do not exist in a vacuum, and they are affected by external sources of information. One of the most common conduits of such information is the smartphone. In other words, the internet, cell phone networks, and nearly limitless information (accurate or otherwise), services, and communication tools are available to almost every patient day and night. In most hospital settings, cell phone use is conceived of as binary (ie, access or no access). Patients cannot have their cell phones in operating rooms or on many locked inpatient psychiatric units. In most other settings, cellphones are a ubiquitous part of hospital milieus. Nonetheless, standards and regulations of cell phone use in North American hospitals have struggled to keep pace with technology.1

Possession of a cell phone on inpatient psychiatry units is typically limited since smartphones jeopardize privacy and confidentiality.2 Restrictions are often justified due to the potential for privacy breeches in the inpatient psychiatric settings. Unit regulations protect vulnerable patients, a principle that supersedes individual patients’ comfort. Yet, the tipping point involving patient autonomy and unit safety is not always clear on many hospital services. Patients tolerate restrictions placed on visiting hours, clothing, and use of tobacco products more readily than they do on cell phone usage.3

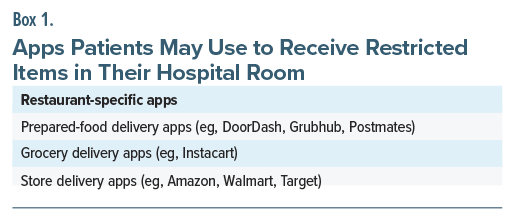

With the advent and expansion of portable technologies and application-based services, cell phone usage can be problematic in hospital settings (Box 1), even beyond privacy concerns. For instance, many apps allow patients to order food, drinks, or other items with just a tap. In cases in which patients have their intake/ fluid restricted, this can jeopardize medical care.

What Is “Contraband”?

Although all hospitals and health care systems have individualized policies, the policies of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) can serve as a reasonable proxy when considering patient entitlements. According to VA policies, patients are entitled to certain legal rights, and they have the right to be visited, communicated with (including the ability to receive unopened mail), to wear clothing of their choice, to have personal possessions and money, and to engage in social interactions, exercise, and worship.4 While these entitlements are broad, they are not all encompassing. Access to contraband or “illegal goods” may be restricted; however, what warrants restriction can be ambiguous.

For example, since cigarettes and other nicotine-containing products are legal, if a patient is 21 years of age or older, these substances are not technically contraband. Most public buildings and hospitals have policies that ban the use of these products on their grounds, especially if they produce smoke or vapors that adversely affect the health and well-being of others. Many health care providers have fielded requests for a “smoke break” from a patient, often balanced by the threat of leaving against medical advice if that smoke break was not allowed. Although even 1 cigarette can adversely impact cardiovascular or pulmonary health, it is unclear how detrimental delaying or foregoing intravenous antibiotics for sepsis or being discharged without correcting a critically low blood sugar or electrolyte abnormality might be. While the potential for danger may be seen as trivial by providers, it may carry tremendous weight for patients. It can provide comfort or a sense of control that hospitalization often strips from patients. Some behaviors can be seen as a way for patients to meet their needs; this insight can be invaluable, as it can rekindle empathy that may have been soured by behaviors displayed under duress and can shift from labeling negative behaviors to align with a patient’s needs. Although not all requests are feasible, developing choices can facilitate patient-provider rapport, or establish a relationship that has been elusive. When faced with a patient who is acting in a manner that a provider sees as unhealthy, it can be easy to overlook the impact of a patient’s values on their decision-making.

How Might Psychiatrists Approach a Patient’s Use of Technology in General Hospital Settings?

Psychiatrists are often consulted when a patient declines recommended interventions or when help is needed to manage a patient’s “difficult” behavior.5 In the case of Mr A, what was initially a consultation for assessment and management of irritability eventually morphed toward providing guidance around how to restrict Amazon orders and understanding the dynamics between a patient and his providers.6

Psychiatrists receive extensive training in the management of transference and countertransference, maintaining calm while setting boundaries in the face of threats, analyzing interpersonal dynamics for diagnostic clues, and using this information to develop, refine, and document case formulations that justify recommendations that might otherwise be seen as withholding. Just as therapists are encouraged to seek supervision when they feel overwhelmed by countertransference, consultation in challenging cases can be a wise response when intense emotional reactions are evoked.7

After receiving a consult request and before seeing a patient, the consultant should consider the treatment team’s stated and unstated needs. What is the team’s reaction to this situation? What impact is that reaction having on patient care? Is the team hoping for a specific outcome? If the consult question as directly stated is answered, will the need for the consultation really be addressed?

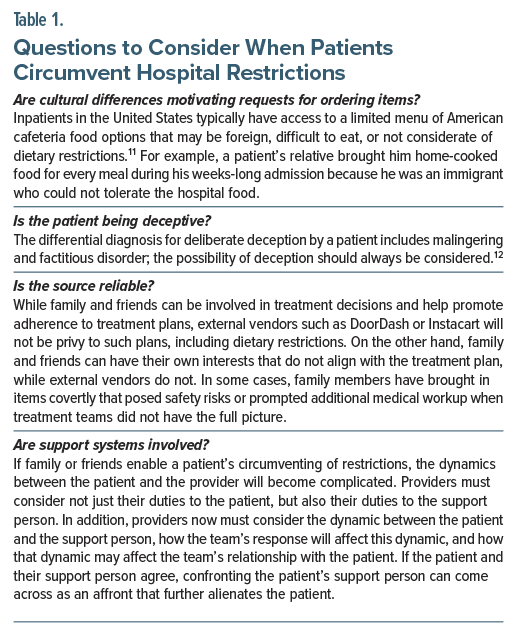

Following a framework of nonviolent communication,8 any behaviors that contradict provider recommendations can be seen as stemming from an unmet need. The advantages of this approach are 2-fold. First, framing behaviors as efforts by patients to meet their needs invites providers to rekindle empathy with the patient that may have been lost. Such reflection can reveal a universal human need that others have met through different means, potentially highlighting differing levels of privilege that drive complex patient-provider dynamics.9,10 Through this lens, malingering to obtain shelter can be seen as an adaptive response to homelessness caused by societal factors rather than individual patient deficiencies. Second, focusing on a patient’s needs rather than on their behaviors will increase the likelihood that a provider will successfully address the root cause. Psychiatrists often interact with patients who have developed maladaptive communication patterns or coping skills due to limitations imposed by social disadvantage, trauma, psychopathology, or the acute stress of an inpatient admission for a medical illness. Focusing on the need helps ensure that patient needs can be addressed, regardless of the maladaptive patterns they have learned to use when advocating for these needs. Drawing from our experiences in which items from outside of the hospital were brought into patient rooms, we suggest considering several questions when patients use alternate means to circumvent hospital restrictions (Table 1).

Can Patients Refuse to Follow Rules That Restrict Their Behavior?

Health care providers often recognize that, despite their best efforts to counsel their patients during an office visit, they have no control over their patients’ behaviors after patients leave their office. Although providers would like their patients to engage in healthy behaviors (eg, eating healthily and getting adequate amounts of exercise), patients decide whether they will follow the recommendations of their health care providers. In inpatient settings, clinicians often feel that patients have entered their turf, and paternalistic patterns of eras past may arise again. For example, dietary orders are often written without consulting the patient because a restrictive diet was deemed medically necessary by the physician of record. However, adherence is likely to be enhanced when such interventions are accompanied by a dialogue between the patient and the provider, sharing information that is intended to achieve a joint decision. Since capacity, or lack thereof, can affect a patient’s ability to decide on treatment decisions, patients with decisional capacity can refuse interventions that are inconsistent with their physicians’ recommendations.

Over several decades, there has been a growing push for, and an acceptance of, a shared decision-making model that involves the bidirectional sharing of information (whereby the physician provides information on treatment options, risks, benefits, and their potential impact while the patient contributes their understanding, values, and preferences).13

How Can Treatment Adherence Be Facilitated?

As modern technologies make it easier for patients to circumvent treatment recommendations in inpatient settings, it is important for all care teams to make every effort to facilitate and enhance treatment adherence whenever possible. Ensuring adequate understanding of the treatment plan and employing shared decision-making13 can aid in enhancing treatment adherence. Furthermore, understanding patients’ values and the values behind their preferences for care can also facilitate treatment adherence.14

When Does Shared Decision-Making Stop?

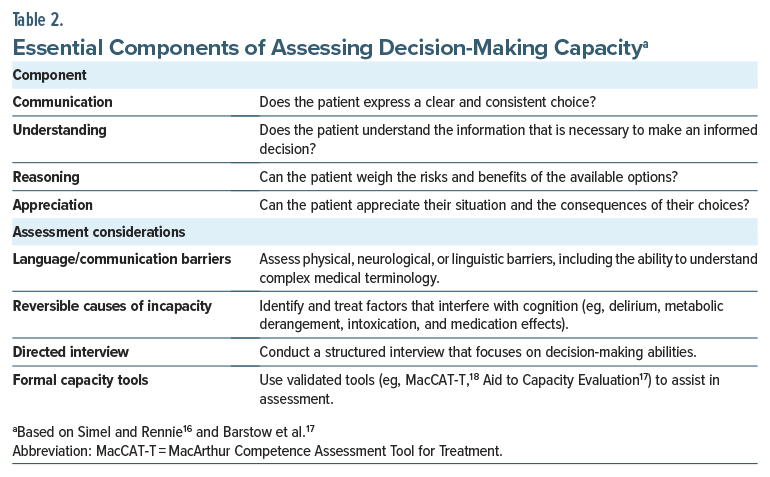

While shared decision-making has become commonplace in medical arenas, certain circumstances may limit its utility (eg, when a patient’s ability to understand, appreciate, or manipulate facts related to a decision is impaired). Therefore, concerns about incapacity warrant further exploration, and difficult cases may benefit from psychiatric consultation (Table 2). Instances involving significant uncertainty, often existential, arise when exploration of the patient’s emotions and values is more appropriate than providing details of a poorly tolerated, last-resort treatment. Situations also arise when the evidence for an intervention’s benefit is limited or when a clinician’s duty to the patient’s safety, or to that of others, may outweigh the patient’s preferences.15

What Happened to Mr A?

Over the course of his hospital stay, Mr A was seen repeatedly by the psychiatry consultation service who attempted to build alliance with support and validation, while also advocating for Mr A by facilitating appropriate communication with his team about his needs. While advocating for Mr A around his wishes for food, this facilitation of communication also served to allow his team to reinforce the medical necessity of dietary restrictions. Mr A continued to demonstrate little understanding of the need for dietary restrictions by frequently suggesting that complying with dietary restrictions would not make a difference for his physical condition. A therapist from the behavioral intervention team saw Mr A several times each week for supportive therapy to enhance coping skills and to address his impulse control around dietary indiscretions. Despite these interventions, Mr A continued to demonstrate little insight into the need for dietary restrictions.

Mr A’s prolonged course was complicated by renal failure (that required hemodialysis), an acute coronary syndrome (that required stenting), and an episode of unresponsiveness that was found to be related to an acute left frontal infarct, precipitating readmission to the ICU. Unfortunately, after 5 months in the hospital, Mr A developed sustained ventricular tachycardia, and he was unable to be resuscitated.

CONCLUSION

Despite numerous efforts to facilitate our patient’s understanding of, and adherence to, medical recommendations (including dietary restrictions), our patient used his cellular phone to purchase food and drinks that were incompatible with his health. This may have been exacerbated by executive dysfunction secondary to cardiopulmonary/renal dysfunction. Although obstacles to adherence can be difficult to navigate, efforts to understand a patient’s reasons for their behaviors are required.

Article Information

Published Online: December 2, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f04031

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: May 2, 2025; accepted August 13, 2025.

To Cite: Zhao E, Wilson B, Harrington M, et al. Treatment nonadherence: sequelae of using digital technologies to circumvent hospital dietary restrictions. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(6):25f04031.

Author Affiliations: University of Vermont Medical Center, Burlington, Vermont (Zhao); Larner College of Medicine, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Zhao, Rustad); Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, New Hampshire (Wilson, Harrington, Rustad, Ho); White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad); Burlington Lakeside VA Community Based Outpatient Clinic, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Wilson, Harrington, Ho); Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts (Stern).

Zhao, Wilson, and Harrington are co-first authors.

Corresponding Author: Patrick A. Ho, MD, MPH, 1 Medical Center Dr, Lebanon, NH 03756 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Dr Rustad is employed by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs Zhao, Wilson, Harrington, and Ho have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- The availability of portable technologies and application-based services can complicate caretaking in the hospital setting, as patients can circumvent medical recommendations.

- It is crucial for health care providers to understand why and when a patient circumvents medical decisions, and to allow empathy to facilitate the doctor-patient relationship.

- Although clinicians hope that their interactions with patients will lead to healthy behaviors, patients have the final say about whether they will follow treatment recommendations.

- Although shared decision-making is typically preferred, treatment recommendations may be followed (with the involvement of a surrogate decision-maker or in an emergency) when a patient’s capacity to make treatment decisions has been lost.

References (18)

- Vincent CJ, Niezen G, O’Kane AA, et al. Can standards and regulations keep up with health technology? JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(2):e64. PubMed

- Adler RH. Bucking the system: mitigating psychiatric patient rule breaking for a safer milieu. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2020;34(3):100–106. PubMed CrossRef

- Salzmann-Erikson M. Limiting patients as a nursing practice in psychiatric intensive care units to ensure safety and gain control. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(4):241–252. PubMed CrossRef

- Rights and Responsibilities of VA Patients and Residents of Community Living Centers. Veterans Health Administration Web site. 2023. Accessed April 7, 2025. https://www.va.gov/health/rights/patientrights.asp

- Umapathy C, Ramchandani D, Lamdan RM, et al. Competency evaluations on the consultation-liaison service: some overt and covert aspects. Psychosomatics. 1999;40(1):28–33. PubMed CrossRef

- Kornfeld DS, Muskin PR, Tahil FA. Psychiatric evaluation of mental capacity in the general hospital: a significant teaching opportunity. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(5):468–473. PubMed CrossRef

- Nadelson T. Emotional interactions of patient and staff: a focus of psychiatric consultation. Psychiatry Med. 1971;2(3):240–246. PubMed CrossRef

- Rosenberg MB, Chopra D. Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life. PuddleDancer Press;2015.

- Rogers R. Models of feigned mental illness. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 1990;21(3):182–188. CrossRef

- Park L, Costello S, Li J, et al. Race, health, and socioeconomic disparities associated with malingering in psychiatric patients at an urban emergency department. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;71:121–127. PubMed CrossRef

- Wong EI l., Mcproud LM, Giampaoli JM. Hospital foodservice and ethnic foods: a survey of hospitals in two counties of Northern California. Foodservice Res Int. 1995;8(4):257–262.

- Beach SR, Taylor JB, Kontos N. Teaching psychiatric trainees to “think dirty”: uncovering hidden motivations and deception. Psychosomatics. 2017;58(5):474–482. PubMed CrossRef

- Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision-making in the physician-patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision-making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651–661. PubMed CrossRef

- Jimmy B, Jose J. Patient medication adherence: measures in daily practice. Oman Med J. 2011;26(3):155–159. PubMed CrossRef

- Elwyn G, Price A, Franco JVA, et al. The limits of shared decision making. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2023;28(4):218–221. PubMed CrossRef

- Simel DL, Rennie D. Medical decision-making capacity. In: The Rational Clinical Examination: Evidence-Based Clinical Diagnosis. McGraw-Hill Education; 2016. Accessed June 10, 2025. https://jamaevidence.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=845§ionid=61357673

- Barstow C, Shahan B, Roberts M. Evaluating medical decision-making capacity in practice. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(1):40–46. PubMed

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T). Professional Resource Press/Professional Resource Exchange;1988.

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!