Abstract

Objective: Dignity and respect are the basis for professional codes and legislation on human treatment. During illness, patients undergo physical, emotional, and social changes and adapt to losses that reshape their self-concept. Some patients keep a stable sense of dignity despite their losses, although their perception of it fluctuates throughout their illness. As symptoms progress, adaptation and the feeling of respect and dignity remain dynamic. The objective of this study is to assess the validity evidence of an adapted version of the Scale of Perception of Respect for and Maintenance of the Dignity of the Inpatient (referred to as the APREMDI in Brazil).

Methods: To culturally adapt and validate the APREMDI for Brazilian Portuguese, a multicenter observational study was conducted. The study included a convenience sample of 337 inpatients from 3 tertiary hospitals in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, between September 2022 and May 2024. All participants provided informed consent. SPSS, Factor, Jamovi, and JASP were used to conduct the statistical analysis.

Results: The data confirmed the model’s adequacy (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin=0.895, Bartlett test: χ2171=3,785.8, P=.000010), high reliability (α=.949, ω=0.951, composite reliability=0.941), and good fit indices.

Conclusion: The APREMDI scale has strong psychometric properties and is applicable for assessing the quality of health care. It was adapted for southeastern Brazil and may not cover all linguistic variations in Portuguese-speaking countries.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25m04019

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Dignity, universally acknowledged as a fundamental human right, is a core principle in ethical, legal, and clinical care frameworks. Likewise, it is also foundational to patient-centered practice. However, its interpretation and operationalization are shaped by cultural, social, and institutional contexts. Particularly in hospital environments, where patients often experience dependency, stigma, and loss of autonomy, the perception of dignity becomes a dynamic and vulnerable dimension of care. In Western societies, dignity is regarded as inherent and indivisible, forming the basis of civil and political rights.1 It is embedded in major international codes, such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,2 the Nuremberg Code,3–5 the Declaration of Helsinki,6 and regional bioethical declarations.7

Frameworks such as the Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illnesses,8 the Salamanca Statement,9 and the Caracas Declaration10 guide mental health policy with an emphasis on autonomy and humane care. In Brazil, Law No. 10,216/200111 restructured psychiatric care toward a rights-based model. Those legal boundaries have turned respect and dignity into legal and moral imperatives, in both psychiatric and general medical settings. Despite these advances, dignity violations persist, often subtly embedded in routine care.12,13 Validated tools for assessing dignity from the patient’s perspective are essential for identifying, quantifying, and addressing such violations.

The Scale of Perception of Respect for and Maintenance of the Dignity of the Inpatient was developed in Spain to assess this construct in hospitalized patients.14,15 Its adaptation to other cultural contexts requires more than direct translation; it demands linguistic, experiential, conceptual, and semantic equivalence through a rigorous process. In Brazil, no instrument has been validated for this purpose, despite increasing emphasis on patient-centered and humanized care.

We adapted the Scale of Perception of Respect for and Maintenance of the Dignity of the Inpatient for Brazilian Portuguese as the APREMDI scale.16 It evaluates 6 dimensions of dignity: privacy/intimacy, integrity, identity, information, respect, and consideration, and is rated on a 1 to 5 Likert scale.17 This study presents the psychometric validation of the APREMDI scale in a diverse inpatient population. By providing a culturally appropriate and statistically sound instrument, this work aims to strengthen health care quality assessment, clinical training, and policy formulation that uphold human dignity in hospital settings.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted to culturally adapt and validate the Scale of Perception of Respect for and Maintenance of the Dignity of the Inpatient14,15 for use in Brazil.16 The adapted version (APREMDI)16 was evaluated in 3 tertiary hospitals in Rio de Janeiro: the Institute of Psychiatry (IPUB/UFRJ) and the Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital (HUCFF/UFRJ), both at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), and the Lourenço Jorge Municipal Hospital (HMLJ). These facilities serve diverse patient populations, including general medical, surgical, and psychiatric inpatients.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The study was approved by the respective institutional ethical review boards: IPUB/UFRJ (register no. 4.678.189, 04/28/2021), HUCFF/UFRJ (register no. 5.035.181, 10/13/2021), and the Municipal Health Department, responsible for HMLJ (register no. 5.118.710, 11/22/2021). All conducted procedures are compliant with the cornerstone ethical guidelines.6,18 All participants provided informed consent after full explanation of the study’s objectives, procedures, and confidentiality safeguards.

Sample Size

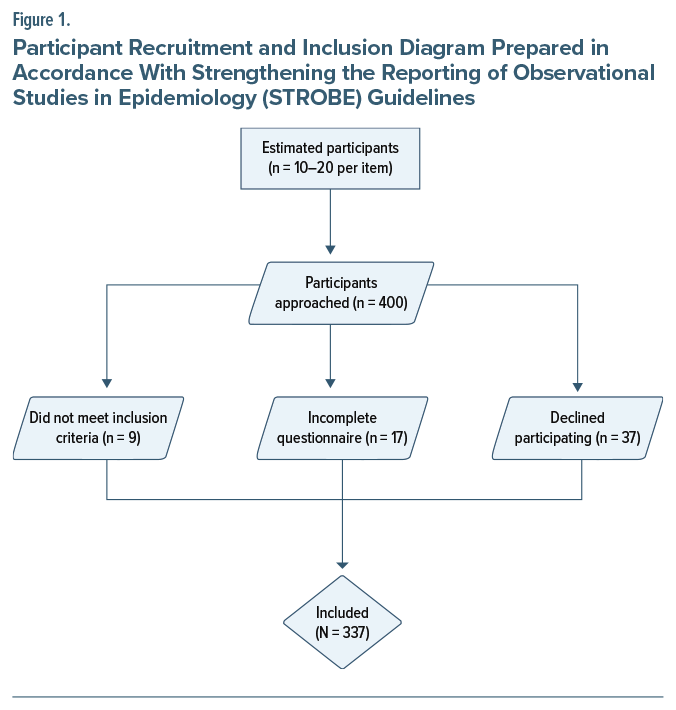

According to Hair et al,19 an absolute minimum of 100 participants is required, with a preferred ratio of at least 5 to 10 participants per item, and ideally up to 20:1 to enhance statistical power and generalizability. With 19 items on the APREMDI, a minimum of 95–190 participants is implied, while the best target would range from 190 to 380 cases.

Additionally, considering potential exclusions and aiming to strengthen subgroup representativeness across diverse hospital units and demographic strata, we added a conservative 20% margin to compensate for attrition or noncompletion. Therefore, the target sample was set between 228 and 456 participants. The final sample included 337 completed responses, which not only exceeds the minimum methodological threshold but also falls within the optimal range for robust exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This ratio of approximately 17.7 participants per item minimizes the risk of model overfitting and enhances the stability and generalizability of the factor structure.

Participants

Eligible participants were adults aged 18 years or older, with a hospitalization length of at least 1 day or discharged within 30 days prior to the interview, that were able to understand and respond to the scale items. Those who declined to take part, withdrew consent, were illiterate, were cognitively impaired, had delirium, or had dementia were ineligible. All included eligible participants were inpatients.

Location and Time

A total of 337 inpatients were recruited through convenience sampling from psychiatric, medical, and surgical units across 3 tertiary hospitals in Rio de Janeiro: HUCFF/UFRJ, IPUB/UFRJ, and HMLJ, between September 2022 and May 2024. The final sample was demographically diverse in terms of age, sex, education level, and hospital unit. Figure 1 illustrates a STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)–compliant20 flow diagram of participant recruitment and inclusion.

Data Collection Procedures

Trained research assistants collected data at the participating hospitals, conducting interviews in private settings to ensure comfort and confidentiality. Sociodemographic variables included age, sex, education level, ward type, hospital, length of hospitalization, and time to complete the APREMDI scale.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS21 version 29.0.2.0 was used for descriptive statistics, convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity via multiple linear regression using APREMDI scores as the dependent variable. Factor Analysis22–24 version 12.04.05 was set to run the EFA, employing polychoric correlation matrices and 1,000 bootstrap25 samples to accommodate the ordinal nature and nonnormal distribution of the data, assessed via the Mardia test,26 using Hot deck imputation27 on parallel analysis,28 robust diagonally weighted least squares,29 and robust Promin rotation.30,31 When the correlation matrix was not definite, the sweet smoothing algorithm32 was applied to stabilize estimates. Model fit and internal consistency were assessed through root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), root mean square of residuals (RMSR), Cronbach α,33 McDonald ω,34 and composite reliability.35,36

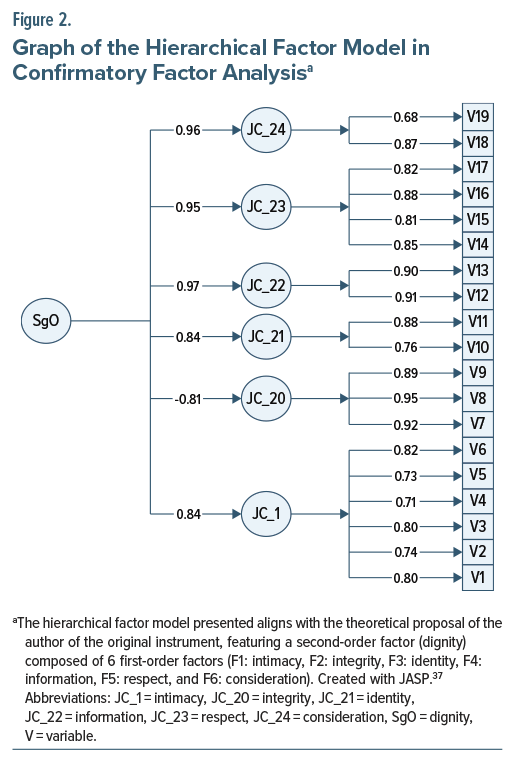

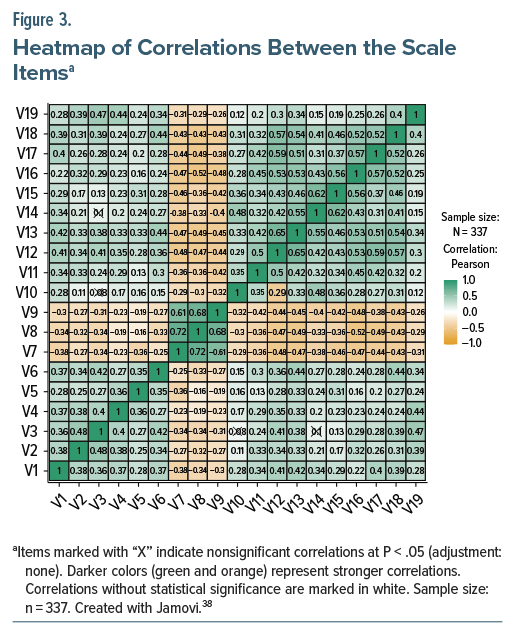

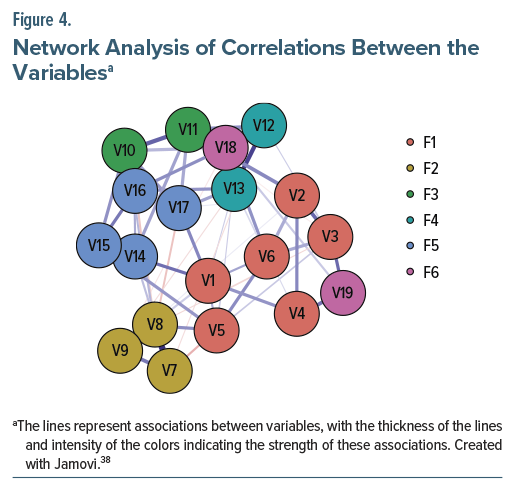

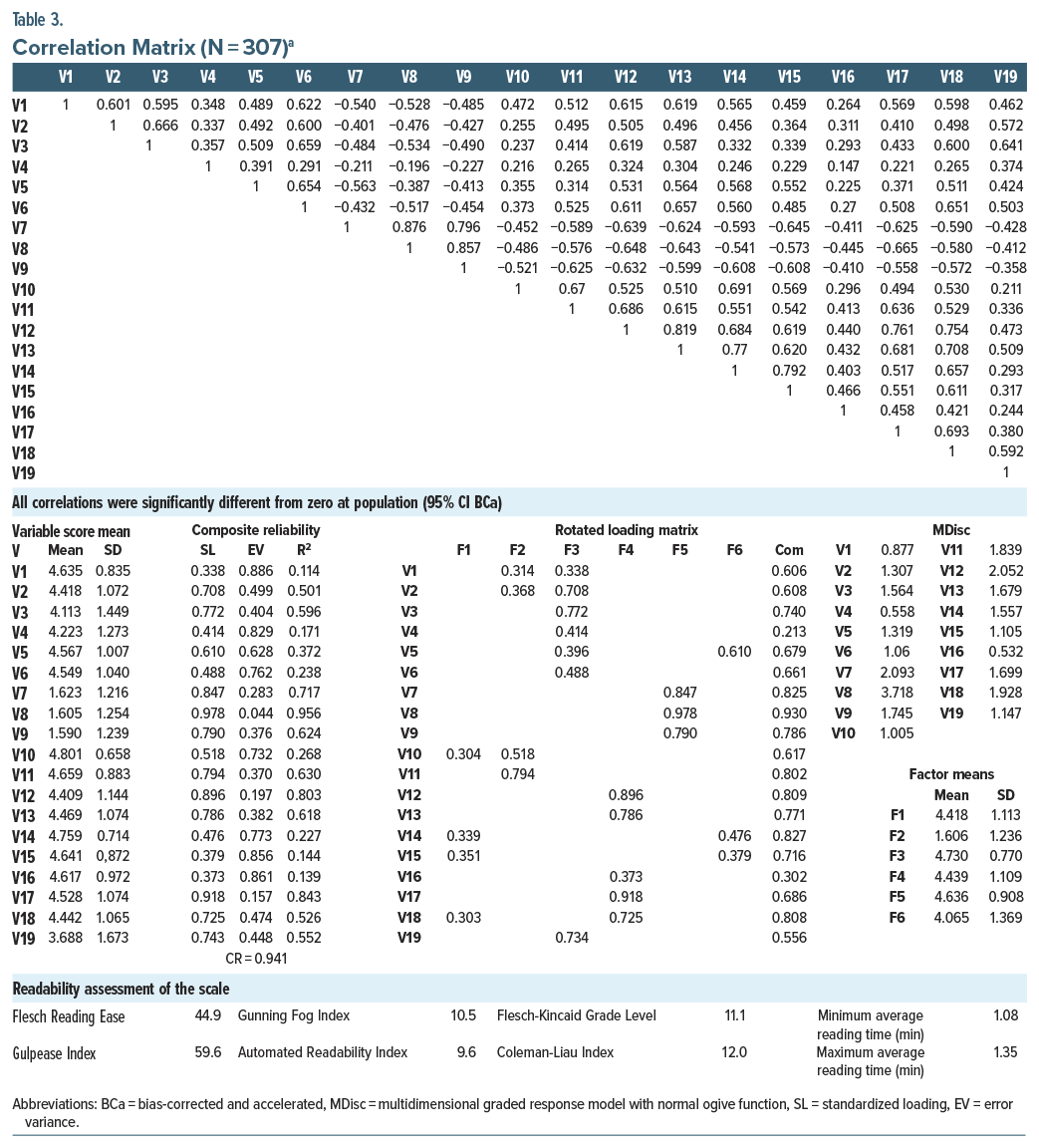

We ran the CFA on JASP37 version 0.17 to evaluate the second-order factorial structure (Figure 2) and Jamovi38 version 2.5 to generate the correlation heatmap and the network graph (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Instruments

Participants completed the APREMDI, a sociodemographic questionnaire, and validated Brazilian versions of the following psychometric instruments: Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-Br),39 Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9),40 Lawton-Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale,41 Pfeffer Functional Activities Questionnaire,42 and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).43 These instruments were used to assess convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity.

Readability Assessment

To assess the comprehensibility of the APREMDI scale, 7 readability indices were applied: Flesch Reading Ease, Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level, Automated Readability Index,44–46 Gulpease Index,47 Gunning Fog Index,48 Coleman-Liau Index,49 and average reading time50 to assess the comprehensibility of the APREMDI and to evaluate its appropriateness for different literacy levels within the sample.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

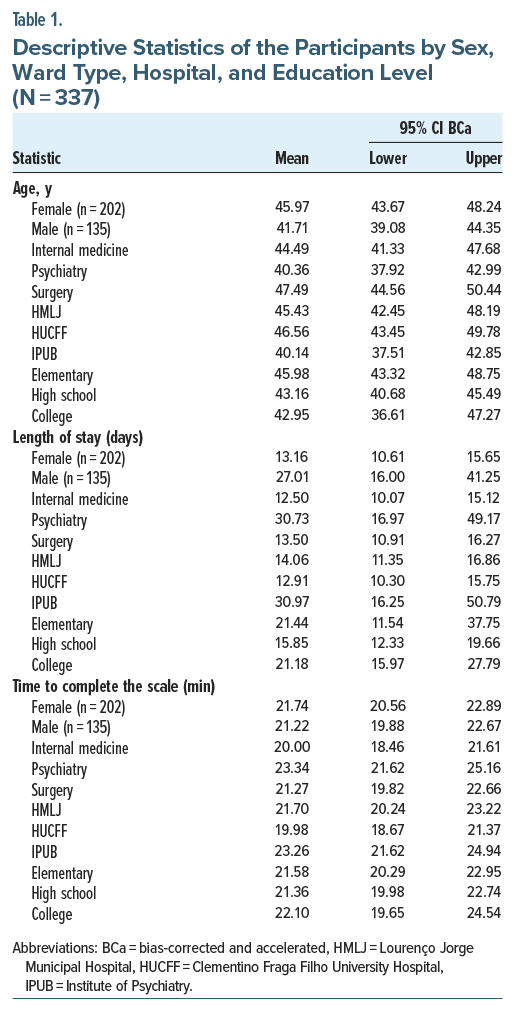

The study included 337 inpatients from psychiatric, surgical, and clinical units across 3 public tertiary hospitals in Rio de Janeiro. Their ages ranged widely, and educational attainment varied from primary education to university level. Descriptive statistics revealed meaningful differences based on demographic and clinical subgroups (Table 1).

Female, surgical, and HUCFF/UFRJ inpatients tended to be older. Male, psychiatric, and IPUB/UFRJ inpatients had longer hospitalization, particularly the less educated. Female, university educated, psychiatric, and IPUB/UFRJ inpatients took longer to complete the scale. These findings show variability in reading time and comprehension that may relate to both clinical status and health literacy.

A 1-way analysis of variance was run to examine whether age, length of hospitalization, and time to complete the scale differed according to participants’ education level, and the results indicated no statistically significant differences among education levels for age (F2,334 = 1.27, P = .281), length of stay (F2,334 = 0.31, P = .731), or time to complete the scale (F2,334 = 0.13, P = .877). Post hoc comparisons using Tukey and Games-Howell tests confirmed the absence of significant pairwise differences for all 3 variables, and none of them violated the homogeneity of variances (Levene P >.05). Effect sizes were negligible (η2 <0.01), suggesting that education level did not explain variance in the studied outcomes.

Validity Evidence

Content validity was previously established, confirming the relevance and clarity of all 19 scale items.16 We used correlations between APREMDI scores and other validated instruments to assess convergent and discriminant validity. The APREMDI showed a weak but statistically significant negative correlation with the HADS total score (r=–0.20, P=.019), suggesting that higher levels of anxiety and depression were associated with a lower perception of dignity. Correlations found with the Lawton-Brody (r=–0.06, P=.468), the Pfeffer (r=–0.09, P=.293), the PHQ-9 (r=–0.13, P=.130), and the CD-RISC-Br (r=0.11, P=.195) were not significant, indicating good discriminant properties.

We examined concurrent validity through Pearson correlations between APREMDI scores and key clinical predictors and found weak negative correlations with anxiety (HADS-A, r=–0.23), depression (HADS-D, r=–0.13; PHQ-9, r=–0.13), functional dependency (Lawton-Brody, r=–0.06), and reduced ability (Pfeffer, r=–0.09), but a weak positive correlation (r=0.11) with resilience (CD-RISC-Br). Although statistically weak, these findings suggest that greater psychological distress and functional decline may be associated with reduced perceived dignity.

When assessing predictive validity through multiple regression analysis with APREMDI scores as the dependent variable, only anxiety (HADS-A) was statistically significant (β=–0.17, P=.031), showing that higher anxiety was a predictor of worse perceived dignity. The model explained a modest part of the variance (R2 = 0.062), suggesting that other factors—potentially interpersonal and contextual—may play a larger role as well.

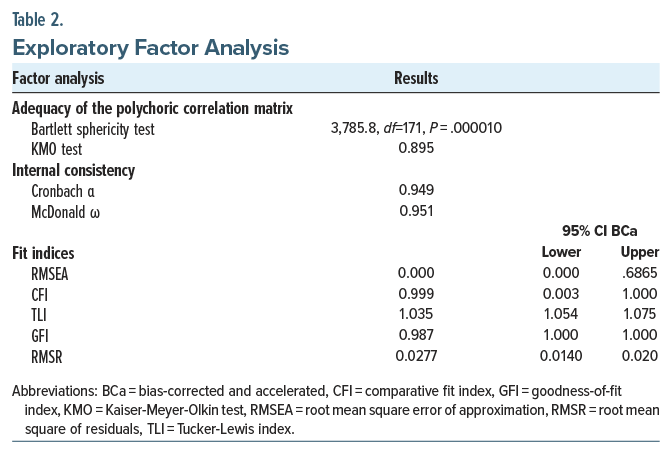

Exploratory Factor Analysis

Sampling adequacy was good: Bartlett test of sphericity was highly significant (χ2 =3,785.8, df=171, P <.001), and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was 0.895 (Table 2). Principal axis factoring with oblique rotation revealed a 6-factor structure. The first factor accounted for 53.56% of the total variance (eigenvalue = 10.19), and the cumulative variance explained by the first 4 factors was 72.45%, suggesting a strong unidimensional structure with meaningful secondary dimensions.

The correlation matrix required sweet smoothing32 due to nonpositive definiteness, which improved the matrix stability for factor extraction. All items had a measure of sample adequacy51 >0.50, suggesting no item removal. The relative difficulty index51 ranged from 0.40 to 0.60, indicating good balance across item responses. Item distributions also passed the quartile of ipsative mean51 criteria, indicating the absence of outlier behavior.

Parallel analysis28 supported the 6-factor solution, with F1 explaining 53.71% of the variance in real data—well above the 95th percentile of randomly simulated datasets (12.36%). Additional indicators of closeness to unidimensionality52 included unidimensional congruence (0.977), explained common variance (0.885), and mean item residual absolute loading (0.227). These indices collectively support the conclusion that the APREMDI is unidimensional, despite its conceptual multidimensionality.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

CFA confirmed the second-order model structure, with 6 first-order factors corresponding to the theoretical dimensions of dignity. Most standardized factor loadings exceeded 0.70, showing strong relationships between latent variables and items. One item (V19) had a loading slightly below this threshold.

Fit indices were good: RMSEA=0.000 (95% CI, 0.000–0.6865), CFI=0.999, TLI =1.035, GFI =0.987, and RMSR=0.028. Despite favorable point estimates, the wide CIs—particularly for RMSEA—suggest potential estimation instability53 and justify further validation in independent samples.

Item Response Theory

We assessed item-level discrimination54 (Table 3) using a multidimensional graded response model55,56 and structural equation modeling.57–59 Discrimination (MDisc) values ranged from 0.532 (V16) to 3.718 (V8). Items V7 and V8 showed particularly strong discrimination, meaning they were extremely sensitive to variations in perceived dignity. Conversely, V4 and V16 showed weaker but acceptable performance. The category intercepts revealed that some items (eg, V7) needed higher latent trait levels for endorsement, consistent with their negative phrasing.

Readability Assessment

Readability analyses (Table 3) showed that the APREMDI scale is moderately complex. Flesch Reading Ease (44.9), Gunning Fog Index (10.5), Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level (11.1), Coleman-Liau Index (12.0), Automated Readability Index (9.6), and Gulpease Index (59.6) suggest that the instrument is proper for readers with at least a high school education. Average reading time ranged from 1.08 to 1.35 minutes. These results confirm that the scale is suitable for educated populations, but it may require simplification for use in lower-literacy settings.

Visual Representations

Figure 2 shows the CFA model, including 6 first-order latent dimensions contributing to a second-order dignity construct. Standardized loadings between the dimensions and the general factor ranged from 0.81 to 0.97, reinforcing the hierarchical nature of the construct. Figure 3 presents a correlation heatmap illustrating relationships between variables, with stronger correlations clustering along the diagonal. Figure 4 is a network graph displaying item-level interactions and factor structure, with central nodes such as V1, V14, and V16 serving as hubs.

DISCUSSION

Our study reports the psychometric validation of the APREMDI for Brazilian Portuguese, confirming its reliability, factorial structure, and alignment with dignity-related constructs in health care. The readability assessment suggests that the scale is best suitable for individuals with at least 11 years of education, but statistical analysis found that differences in age, hospitalization length, or scale completion time across educational groups were not significant, reinforcing the scale’s generalizability. Otherwise, the small effect sizes found require a cautious interpretation, as they underscore the need for further research into potential sociodemographic or clinical moderators. Possible solutions include testing the scale with diverse samples, developing a simplified version or assisted format of the APREMDI for those with lower literacy.

EFA and CFA revealed a cohesive structure with strong fit indices, though some RMSEA uncertainty suggests the need for replication. Likewise, the APREMDI revealed excellent reliability: Cronbach α, McDonald ω, and composite reliability. It is also sensitive, especially in detecting respect and dignity violations, reinforcing its value for identifying areas for clinical improvement.

Dignity is especially at risk in institutional settings, where patients often experience dependency, loss of control, and impersonal care—in both psychiatric and general hospitals. The APREMDI offers a structured, patient-centered tool to assess perceptions of respect and dignity, enhancing health service evaluation. Likewise, anxiety symptoms were associated with lower APREMDI scores, highlighting the psychological relevance of dignity and suggesting that patients in distress may perceive care as less respectful—consistent with prior findings linking emotional well-being to perceived care quality.

Clinically, the APREMDI can be applied across inpatient settings to evaluate respect-related experiences, inform quality improvement, and guide ethics reviews or satisfaction assessments. Its 6-factor structure allows targeted feedback for training in humanized care and communication. Additionally, the scale can monitor ethical practices, particularly in psychiatric contexts where dignity may be compromised, supporting reflective practice and institutional accountability.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The convenience sample from 3 southeastern Brazilian hospitals may limit generalizability, as it may not capture the full cultural and geographic diversity of the country; adaptations may be needed for northern, southern, rural, or indigenous populations.

While model fit indices were strong, the wide RMSEA CI suggests possible overfitting, highlighting the need for replication in larger, independent samples. Although negatively worded items were reverse-scored to reduce response bias, some (eg, V7, V8) showed higher variability and lower means, suggesting a need to refine their wording for clarity without compromising psychometric quality. Self-report data, despite confidentiality measures, may have been influenced by social desirability or power dynamics, especially in psychiatric settings, which may require triangulation with interviews or observations to enhance insight. Lastly, readability indices do not fully capture cognitive or contextual barriers, requiring further validation in low-literacy and cognitively impaired populations.

CONCLUSION

The APREMDI is a reliable, valid, and practical tool for assessing inpatients’ perceptions of dignity in Brazilian hospitals, capturing a complex, multidimensional construct through a concise, culturally adapted format. Its strong psychometric performance and clinical utility make it suitable for quality assessment, training, ethical review, and patient-centered care in both psychiatric and general settings. Future research should explore its application in other Brazilian regions and Portuguese-speaking countries, examine links with clinical outcomes, and test its sensitivity to institutional changes. As dignity gains importance in ethical health care, the APREMDI offers a valuable, patient-informed metric to promote more respectful and humane care.

Article Information

Published Online: February 19, 2026. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25m04019

© 2026 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: July 13, 2025; accepted October 27, 2025.

To Cite: Pereira Dutra PE, Quagliato LA, Zaragoza BC, et al. Validation of the adapted scale of perception of respect for and maintenance of the dignity of the inpatient for brazilian portuguese: a multicenter cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2026;28(1):25m04019.

Author Affiliations: Laboratory of Panic and Respiration, Institute of Psychiatry, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (LABPR/IPUB/UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Pereira Dutra, Quagliato, Horato, de Brito, Jacarandá, Walter, Marques, dos Santos, Nardi); Escola Universitària D’Infermeria, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain (Zaragoza); Department of Psychiatry and Forensic Medicine, Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (HUCFF/UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (da Costa); Psychiatric Ward, Lourenço Jorge Municipal Hospital (HMLJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (da Silva); Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro (UNIRIO), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (de Brito, Jacarandá, Walter); Faculty of Medicine, Grande Rio University (Unigranrio), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Marques); Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (dos Santos).

Corresponding Author: Pablo Eduardo Pereira Dutra, MD, MSc, Laboratory of Panic and Respiration, Institute of Psychiatry, Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (LABPR/ IPUB/UFRJ). Av. Venceslau Bras, 71, Botafogo, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 22290-140 ([email protected]).

Author Contributions: PEPD was responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing (original draft), and writing (review and editing). LAQ was responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing (review and editing). NGGH was responsible for data curation, formal analysis, validation, visualization, and writing (original draft). CBFC was responsible for the investigation, project administration, and supervision. BCZ was responsible for conceptualization, data curation, methodology, supervision, visualization, and writing (review and editing). CRMS was responsible for the investigation, project administration, data curation, and supervision. ALMB was responsible for the investigation, visualization, and writing (original draft). JMJ was responsible for the investigation, visualization, and writing (original draft). KRW was responsible for the investigation, visualization, and writing (original draft). ALPMM was responsible for the investigation, visualization, and writing (original draft). LGBS was responsible for the investigation, visualization, and writing (original draft). AEN was responsible for conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, visualization, and writing (review and editing). All authors have read and approved the final submitted version and take public responsibility for all aspects of the work.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

Role of the Sponsor: The Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES) is a federal government agency that supports master’s, doctoral, and postdoc scholarships.

Acknowledgments: The authors express their sincere gratitude to the leadership and clinical staff of the Clementino Fraga Filho University Hospital of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (HUCFF/UFRJ), the Institute of Psychiatry of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (IPUB/UFRJ), and the Lourenço Jorge Municipal Hospital (HMLJ) for their institutional support throughout the research process. They are also grateful to the Research Ethics Committees of HUCFF/UFRJ, IPUB/UFRJ, and the Municipal Health Department of the city of Rio de Janeiro for their ethical oversight and approval of the study. They also extend heartfelt thanks to the members of the expert panel who contributed to the cultural adaptation of the scale, as well as to the nursing teams, medical residents, and students who were actively involved in the data collection phase, as their collaboration and commitment were fundamental to the successful development and execution of this project. The authors also express their sincere gratitude to the following researchers for generously granting authorization to use their respective instruments in the validation process of this study: Professor Jonathan R. T. Davidson, MD, for the Portuguese version of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (RISC-Br); Rodrigo de Souza, MSc, for the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9); Jair Sindra Virtuoso Jr, PhD, for the Lawton-Brody Scale; Neury José Botega, PhD, for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS); and Marina Carneiro Dutra, MSc, for the Pfeffer Scale. Their valuable contributions significantly enhanced the methodological rigor and quality of this research.

Additional Information: This manuscript follows the STROBE20 (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for cross-sectional studies. The STROBE checklist was applied throughout the study’s design, conduct, and reporting to ensure methodological rigor and transparency. The authors addressed all relevant checklist items and acknowledged any reporting limitations, such as the sample size justification and details of the recruitment flow, within the manuscript.

ORCID: Pablo Eduardo Pereira Dutra: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3970-5668; Laiana Azevedo Quagliato: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6928-5847; Natia Gabriela Griffo Horato: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0883-2015; Carolina Barros Ferreira da Costa: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5624-9444; Beatriz Campillo Zaragoza: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4118-7417; Claudia Regina Menezes da Silva: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2659-4252; Ana Luiza Marques de Brito: https://orcid.org/0009-0007-2803-9061; Julia Monteiro Jacarandá: https://orcid.org/0009-0001-9099-3434; Karina Ramos Walter: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-4008-9441; Ana Lutz Peixoto Mazza Marques: https://orcid.org/0009-0008-6853-8903; Lucas Gomes Barreto dos Santos: https://orcid.org/0009-0002-5034-551X; Antonio Egidio Nardi: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2152-4669

Clinical Points

- The APREMDI scale allows clinicians to quantitatively assess patients’ perceptions of respect and dignity during hospitalization, helping to identify subtle dignity violations that may compromise recovery and satisfaction.

- Higher anxiety levels predict lower dignity perception, indicating that monitoring psychological distress should be an integral part of inpatient care to preserve patients’ sense of respect and autonomy.

- Implementing APREMDI-based feedback in wards can guide targeted training in communication and ethical sensitivity, improving humanized care practices and institutional accountability across medical, surgical, and psychiatric settings.

References (59)

- Debes R. Dignity. In: Zalta EN, Nodelman N, eds. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University; 2023. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dignity/

- United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. United Nations; 1948. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. The Nuremberg Code [Internet]. Washington, DC, USA: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 2025. https://ushmm.org/content/en/article/the-nuremberg-code

- Taylor T. Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10. Nuremberg [Internet]. Crimeofaggression.info. U. S. Government Printing Office; 1949. https://crimeofaggression.info/documents/6/1945_Control_Council_Law_No10.pdf

- Shuster E. Fifty years later: the significance of the Nuremberg Code. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(20):1436–1440. PubMed CrossRef

- WMA declaration of Helsinki – ethical principles for medical research involving human participants. Wma.net. [cited 2025 Feb 1]. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki/.

- Centro de Bioética. Conselho Regional de Medicina do Estado de São Paulo (CREMESP). 2002. [cited 2025 Feb 10]. http://www.bioetica.org.br/? siteAcao=DiretrizesDeclaracoes

- United Nations. Principles for the protection of persons with mental illness and the improvement of mental health care. United Nations - Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner; 1991. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/principles-protection-persons-mental-illness-and-improvement#:∼:text=1.,dignity%20of%20the%20human%20person

- World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality, Unesco; 1994. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000139394

- World Health Organization, Pan American Health Organization. Caracas Declaration - Conference on the Restructuring of Psychiatric Care in Latin America within the Local Health Systems. Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization (PAHO/WHO). https://www.globalhealthrights.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/Caracas-Declaration.pdf

- Lei no. 10.216, de 6 de abril de 2001. Dispõe sobre a proteção e os direitos das pessoas portadoras de transtornos mentais e redireciona o modelo assistencial em saúde mental. Gov.br. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República. 2001. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/leis_2001/l10216.htm

- Chochinov HM. Defending dignity. Palliat Support Care. 2003;1(4):307–308. PubMed CrossRef

- Loch AA, Guarniero FB, Lawson FL, et al. Stigma toward schizophrenia: do all psychiatrists behave the same? Latent profile analysis of a national sample of psychiatrists in Brazil. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13(1):92. PubMed CrossRef

- Campillo B, Corbella J, Gelpi M, et al. Percepción del respeto y mantenimiento de la dignidad en pacientes hospitalizados. Acta Bioeth. 2020;26(1):61–72. CrossRef

- Campillo B, Corbella J, Gelpi M, et al. Development and validation of the Scale of Perception of Respect for and Maintenance of the Dignity of the Inpatient [CuPDPH]. Ethics Med Public Health. 2020;15(100553):100553. CrossRef

- Pereira Dutra PE, Quagliato LA, Curupaná FT, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Scale of Perception of Respect for and Maintenance of the Dignity of the Inpatient (CuPDPH) to Brazilian Portuguese and its psychometric properties - a multicenter cross-sectional study. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2024;79(100328):100328. PubMed CrossRef

- Likert R. A Technique for the measurement of attitudes. Woodworth RS. Archives Psychol. 1932;22(140):5–55.

- Conselho Nacional de Saúde (CNS). Resolução no 466, de 12 de dezembro de 2012. Imprensa Nacional; 2012. https://www.gov.br/conselho-nacional-de-saude/pt-br/acesso-a-informacao/legislacao/resolucoes/2012/resolucao-no-466.pdf/view

- Hair J, Anderson R, Babin B, et al, Exploratory factor analysis. In: Hair J, Anderson R, Babin B, et al, eds. Multivariate Data Analysis. 8th ed. Cengage Learning EMEA;2018:121–188.

- Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13(Suppl 1):S31–S34. PubMed CrossRef

- IBM Corp. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences. IBM; 2024. https://www.ibm.com/br-pt/products/spss-statistics

- Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ. FACTOR: a computer program to fit the exploratory factor analysis model. Behav Res Methods. 2006;38(1):88–91. PubMed CrossRef

- Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ. Factor 9.2: a comprehensive program for fitting exploratory and semiconfirmatory factor analysis and IRT models. Appl Psychol Meas. 2013;37(6):497–498.

- Ferrando PJ, Lorenzo-Seva U. Program FACTOR at 10: origins, development and future directions. Psicothema. 2017;29(2):236–240. PubMed CrossRef

- Lambert ZV, Wildt AR, Durand RM. Approximating confidence intervals for factor loadings. Multivariate Behav Res. 1991;26(3):421–434. PubMed CrossRef

- Mardia KV. Measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis with applications. Biometrika. 1970;57(3):519. CrossRef

- Lorenzo-Seva U, Van Ginkel JR. Multiple Imputation of missing values in exploratory factor analysis of multidimensional scales: estimating latent trait scores. An Psicol. 2016;32(2):596. CrossRef

- Timmerman ME, Lorenzo-Seva U. Dimensionality assessment of ordered polytomous items with parallel analysis. Psychol Methods. 2011;16(2):209–220. PubMed CrossRef

- DiStefano C, Morgan GB. A comparison of diagonal weighted least squares robust estimation techniques for ordinal data. Struct Equ Model. 2014;21(3):425–438. CrossRef

- Lorenzo-Seva U. Promin: a method for oblique factor rotation. Multivariate Behav Res. 1999;34(3):347–365. CrossRef

- Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ. Robust Promin: a method for diagonally weighted factor rotation. Lib Rev Peru Psicol. 2019;25(1):99–106. CrossRef

- Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ. Not positive definite correlation matrices in exploratory item factor analysis: causes, consequences and a proposed solution. Struct Equ Model. 2021;28(1):138–147. CrossRef

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297–334. CrossRef

- McDonald RP. Test Theory: A Unified Treatment. Psychology Press; 2013. CrossRef

- Jöreskog KG. Statistical analysis of sets of congeneric tests. Psychometrika. 1971;36(2):109–133.

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. CrossRef

- Berger JO, Forster J, Clyde MA, et al. A fresh way to do statistics. JASP - Free and User-Friendly Statistical Software. University of Amsterdam; 2021. https://jasp-stats.org

- Love J, Dropmann D, Selker R, et al. The Jamovi Project (2024). Jamovi (Version 2.5) [Computer Software]. The Jamovi Team; 2024. https://www.jamovi.org/about.html.

- Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76–82. PubMed CrossRef

- Souza R de, Feitosa FB, Rodríguez TDM, et al. Rastreamento de sintomas de depressão em policiais penais: estudo de validação do PHQ-9. Rev Bras Multidiscip. 2021;24(2):180–190.

- Santos RL dos, Virtuoso Júnior JS. Confiabilidade da versão brasileira da Escala de Atividades Instrumentais da Vida Diária. Rev Bras Em Promoção Saúde. 2008:290–296.

- Dutra MC. Validação do questionário de Pfeffer para a população idosa brasileira. Universidade Católica de Brasília; 2014. https://bdtd.ucb.br:8443/jspui/bitstream/123456789/1199/1/Marina%20Carneiro%20Dutra.pdf

- Botega NJ, Bio MR, Zomignani MA, et al. Rev Saude Publica. 1995;29(5):355–363. PubMed CrossRef

- Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. J Appl Psychol. 1948;32(3):221–233. PubMed CrossRef

- Houle CO. Marks of readable style: a study in adult education. Rudolf flesch Libr Q. 1945;15(1):85–85. CrossRef

- Kincaid JP, Fishburne RP, Rogers RL, et al. Derivation of new readability formulas (Automated readability index, Fog Count and Flesch reading Ease formula) for Navy enlisted personnel. In: Kerr NJ, ed. Naval Air Station Memphis. Naval Technical Training Command; 1975. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1055&context=istlibrary

- Lucisano P, Piemontese ME. Gulpease: una formula per la predizione della leggibilita di testi in lingua italiana. Scuola Città. 1988(3):110–124.

- Gunning R. Technique of clear writing. McGraw Hill Higher Education; 1968.

- Coleman M, Liau TL. A computer readability formula designed for machine scoring. J Appl Psychol. 1975;60(2):283–284. CrossRef

- Nielsen J. How little do users read? Nielsen Norman Group; 2008. https://www.nngroup.com/articles/how-little-do-users-read/

- Lorenzo-Seva U, Ferrando PJ. MSA: the forgotten index for identifying inappropriate items before computing exploratory item factor analysis. Methodol (Gott). 2021;17(4):296–306. CrossRef

- Ferrando PJ, Lorenzo-Seva U. Assessing the quality and appropriateness of factor solutions and factor score estimates in exploratory item factor analysis. Educ Psychol Meas. 2018;78(5):762–780. PubMed CrossRef

- Marsh HW, Hau K-T, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Struct Equ Model. 2004;11(3):320–341. CrossRef

- Ferrando PJ, Lorenzo-Seva U. A note on improving EAP trait estimation in oblique factor-analytic and item response theory models. Psicol [Internet]. 2016;37:235–247.

- Muthén B, Kaplan D. A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1985;38(2):171–189.

- Muthén B, Kaplan D. A comparison of some methodologies for the factor analysis of non-normal Likert variables: a note on the size of the model. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 1992;45(1):19–30.

- Reckase MD. The difficulty of test items that measure more than one ability. Appl Psychol Meas. 1985;9(4):401–412. CrossRef

- Kuo T-C, Sheng Y. Bayesian estimation of a multi-unidimensional graded response IRT model. Behaviormetrika. 2015;42(2):79–94. CrossRef

- Samejima F.. Normal ogive model on the continuous response level in the multidimensional latent space. Psychometrika. 1974;39(1):111–121. CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!