Lessons Learned at the Interface of Medicine and Psychiatry

The Psychiatric Consultation Service at Massachusetts General Hospital sees medical and surgical inpatients with comorbid psychiatric symptoms and conditions. During their twice-weekly rounds, Dr Stern and other members of the Consultation Service discuss diagnosis and management of hospitalized patients with complex medical or surgical problems who also demonstrate psychiatric symptoms or conditions. These discussions have given rise to rounds reports that will prove useful for clinicians practicing at the interface of medicine and psychiatry.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25f03990

Author affiliations are listed at the end of this article.

Have you ever encountered a patient with bodily symptoms who was not reassured by a comprehensive examination and medical workup? Have you been uncertain about whether the cause of such symptoms was neurologic, psychiatric, or neuropsychiatric? Have you wondered when and how best to evaluate such symptoms? Have you been perplexed by how to treat such an individual over the short and long terms? If you have, then the following case vignette and discussion should prove useful.

CASE VIGNETTE

Mr A, a 60-year-old man with hypertension, hypothyroidism, and a history of prostate cancer, was in his usual state of health until the past few months when his brother, mother, and father all passed away, and he underwent a prostatectomy for prostate cancer.

At his baseline, Mr A was mild-mannered, affable, and outgoing. However, he developed racing and ruminative thoughts at night and had been focusing on death (eg, thinking that he was of more value being dead than alive). He became preoccupied with his heart rate and blood pressure, believing that he had a serious health problem that would take his life. After an episode of fecal incontinence, he started to worry that he was contaminating everything around him. He lost 15 lb and felt “constantly tense.” He worried that he had “failed at life” and that he was headed to “financial ruin” (although there was no evidence of this). He said the only deterrent to taking his life was being “chicken.” Mirtazapine was started and titrated to 30 mg/d; however, he thought it impaired his concentration and made him feel as though he was “in a fog”; therefore, mirtazapine was discontinued. Citalopram was then titrated to 40 mg/d; it reduced his depressed mood and his libido. Bupropion 100 mg/d was added to counter citalopram-related sexual side effects. It was discontinued, as it made him feel worse.

Mr A’s fear of having a serious and yet undiagnosed illness escalated over the next month. He believed that his kidneys had “shut down” despite having a normal creatinine level (0.80; normal range, 0.7–1.3 mg/dL). He was concerned about “dying from toxemia.” Since he was convinced that his “digestive tract was packed,” he refused to eat or drink.

On mental status examination, he had poor eye contact, an exasperated facial expression, and he sighed frequently. His abdominal examination and bowel x-rays were unremarkable. He said that the only thing that would convince him that his intestines were not impacted was if his intestines were surgically opened so that he could see inside. When he was told that his constipation was due to his lack of oral intake, he countered, “I know that this is the theory.”

Initially, Mr A refused to take medications, saying that they will “stay at the top” due to his obstructed bowels. When asked about alternatives to medications he said, “You mean electric shock? No way.”

DISCUSSION

What Are Somatic Delusions?

People with somatic delusions are convinced that there is something medically, physically, or biologically wrong with part or all of their body (internally or externally), without having any evidence to support such a viewpoint.1 Somatizing (ie, the tendency to experience and express psychological distress as physical symptoms) becomes delusional when the belief is bizarre within their cultural context, and the belief is held with absolute certainty despite evidence of the contrary.2 For example, an individual who somatizes may experience stomach pain, become fixated on their symptoms, and believe something is wrong despite testing that fails to show abnormalities. A person with a somatic delusion may believe that bugs are eating their insides; normal test results fail to change their belief. Somatizing, as a component of mental illness, is associated with a lower quality of life and overall health and a greater risk for suicide.1 Somatic preoccupations impact clinical outcomes, their treatment can be difficult, and there are no clearly effective practice guidelines for them.

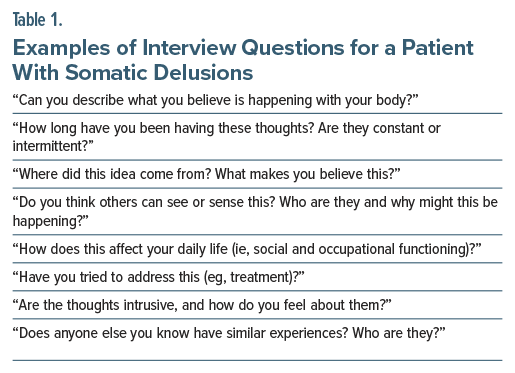

What Questions Would Be Helpful to Ask a Patient Who Reports Somatic Delusions?

Interviewing patients about somatic delusions can be difficult and at times lead to a negative reaction from the patient. Even providing reassurance often conflicts with their experience and can elicit anger rather than appreciation. With that in mind, it is helpful to have some questions that can help gather information needed for a diagnosis. Table 1 includes suggestions of questions that could be asked about somatic delusions.

How Do Overvalued Ideas Differ From Delusions?

The concept of the overvalued idea was proposed by Carl Wernicke over 100 years ago as a solitary belief that can be considered as justified in the context of a person’s life history and personality, which goes on to determine an individual’s actions to a high degree.2 The disturbance in functioning and the subjective suffering it causes in the patient or in others give these types of ideas the qualifier of being overvalued.2

A delusion is a false idea or belief that the patient holds with an extraordinarily high degree of conviction, and that is incongruent with the patient’s social, cultural, and educational background.2 Some delusions appear spontaneously (ie, they are primary), while others are brought on by a specific setting, a perception, or a memory (ie, they are secondary). Contrary to the incomprehensibility that characterizes primary delusions, secondary delusions appear understandable in the context of other abnormal phenomena (eg, an abnormal mood, abnormal perception, or a primary abnormal belief).

Overvalued ideas develop from assumptions and beliefs that are shared by other members of the same culture, while delusions are false ideas unique to their possessor.2 Compared to the phenomenology of secondary delusions, prior abnormal phenomenon cannot explain the presence of an overvalued idea. When differentiating between an overvalued idea and an obsession (which is often ego dystonic, ie, causes distress and discomfort), it should be noted that although both types of phenomena may dominate mental activity, the patient does not try to fight an overvalued idea but instead enjoys, amplifies, and defends it, resulting in the idea becoming more resistant to challenge as well as to treatment.2

What Conditions Involve Somatic Delusions?

Somatic delusions are not limited to a single psychiatric diagnosis; rather, they represent a subtype of delusional thinking that can occur across a range of conditions and can manifest in various ways. Somatic delusions are observed in schizophrenia spectrum and related disorders (eg, delusional disorder, monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis, schizophrenia, and schizoaffective disorder), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and related disorders (eg, body dysmorphic disorder [BDD]), bipolar and related disorders (eg, psychosis occurring during manic or depressive episodes of bipolar disorder), depressive disorders (eg, psychosis in the context of unipolar depression), substance-induced psychosis, and psychosis secondary to medical conditions (eg, encephalopathy or delirium).

Schizophrenia Spectrum and Related Disorders

Schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders are characterized by disturbances in 1 or more of the following domains (Criterion A of schizophrenia in the DSM-5-TR): delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thought, disorganized behavior, and negative symptoms. Both schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders may exhibit somatic delusions, although they are observed less often than other types of delusions (eg, persecutory, paranoid, and erotomanic).1,3 In a study of patients with first-episode psychosis, 18% were found to have somatic delusions.3 These delusions may be classified as bizarre or nonbizarre, with bizarre somatic delusions (eg, the belief that an alien implanted a microchip in one’s brain) being more typical in primary psychotic disorders. Delusional pregnancy, in which individuals falsely believe that they are pregnant despite having no objective signs of pregnancy, is most commonly reported in patients with schizophrenia, although it may be seen in mood disorders.4

Delusional disorder is characterized by the presence of 1 or more delusions for at least 1 month without meeting criteria for schizophrenia.5 The somatic subtype accounts for approximately 5% of cases, with a lifetime prevalence of about 0.2% in the general population.6 Somatic delusions observed in delusional disorder commonly include the belief that an individual is infested with insects, parasites, or other foreign bodies; has an internal parasite; or that certain parts of the body are deformed, nonfunctional, or diseased.7 Delusional parasitosis is one such manifestation, characterized by a fixed belief of being infested with insects or parasites, often accompanied by tactile hallucinations.8 Morgellons disease, a subtype of delusional infestation, involves the belief that fibers or filaments are emerging from the skin.9 Monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis (a term first used in the 1970s) was added to the DSM-IV as delusional disorder, somatic type10; it remains a subset of delusional disorder in the DSM-5-TR.5 This condition involves the delusional belief of having a physical deformity or medical illness.11

OCD and Related Disorders

BDD, formerly termed dysmorphophobia, is characterized by a preoccupation with perceived flaws in physical appearance that are unnoticeable or slight to others. Individuals with BDD may obsess or perform repetitive behaviors related to these concerns (eg, mirror checking, grooming, comparing appearance) that leads to functional impairment; their level of insight may be good, absent, or delusional. Patients should not be given an additional diagnosis of delusional disorder unless their beliefs exceed what is typical for someone with BDD (ie, someone with known BDD believes they are being poisoned).5

In cases in which insight is absent, the belief in having a bodily defect is held with delusional intensity. Olfactory reference syndrome (ORS) is considered when individuals are preoccupied with the belief that they are emitting a foul or offensive body odor. The DSM-5-TR5 classifies ORS as OCD, like jikoshu-kyofu, a condition observed in people from Japan who are preoccupied with the fear of having offensive body odor.12

Mood Disorders (Bipolar and Related Disorders, Depressive Disorders)

Somatic delusions may arise within the context of a mood disorder, particularly when psychotic features are present. In major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features, delusions often align with depressive themes. For example, an individual may develop Cotard’s syndrome, a nihilistic somatic delusion characterized by beliefs that the body is decomposing, organs are missing, or that one is dead. Often, these mood-congruent delusions occur when someone has a psychotic depression, but the condition may occur broadly in primary psychotic illnesses or along with a primary medical condition.13 Similarly, bipolar disorder can present with psychotic features during manic or depressive episodes. Although less common than mood-congruent delusions, somatic delusions may occur.14

Substance-Induced Psychosis

Although there is limited literature directly linking somatic delusions specifically to recreational or medicinal substances, a range of pharmacologic agents can induce psychosis, including somatic delusions. Psychosis has been reported in the setting of either intoxication or withdrawal from nearly all recreational substances (including alcohol, amphetamines, cannabis, cocaine, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, PCP [phencyclidine], sedative-hypnotics, and synthetic cannabis).15 Lorazepam, prescribed to manage anxiety associated with psychosis and agitation, can be deliriogenic, which may exacerbate psychotic symptoms in vulnerable individuals. Delusional parasitosis has been particularly associated with stimulant use (eg, methamphetamines, cocaine), alcohol withdrawal, and iatrogenic side effects (eg, from antibiotics [such as ketoconazole, ciprofloxacin], topiramate, amantadine, or steroids).8 Many prescribed medications can induce psychosis, although steroids, antiepileptics, antimalarials, and antiretrovirals are the most reported agents.16

Psychosis Due to Medical Conditions

A variety of medical conditions can induce psychosis (eg, with delirium or encephalopathy), sometimes accompanied by somatic delusions. A thorough medical evaluation is warranted when psychosis presents acutely, especially among children, older adults, or individuals without a psychiatric history. Underlying etiologies include metabolic disturbances, temporal lobe epilepsy, Huntington disease, multiple sclerosis, autoimmune encephalitis, autoimmune disorders, neurocognitive disorders, and Parkinson disease with psychosis.17 Infectious diseases (eg, tuberculosis, leprosy, syphilis, HIV infection) have been linked to delusional parasitosis.8

How Can Conditions That Involve Somatic Delusions Be Distinguished From One Another?

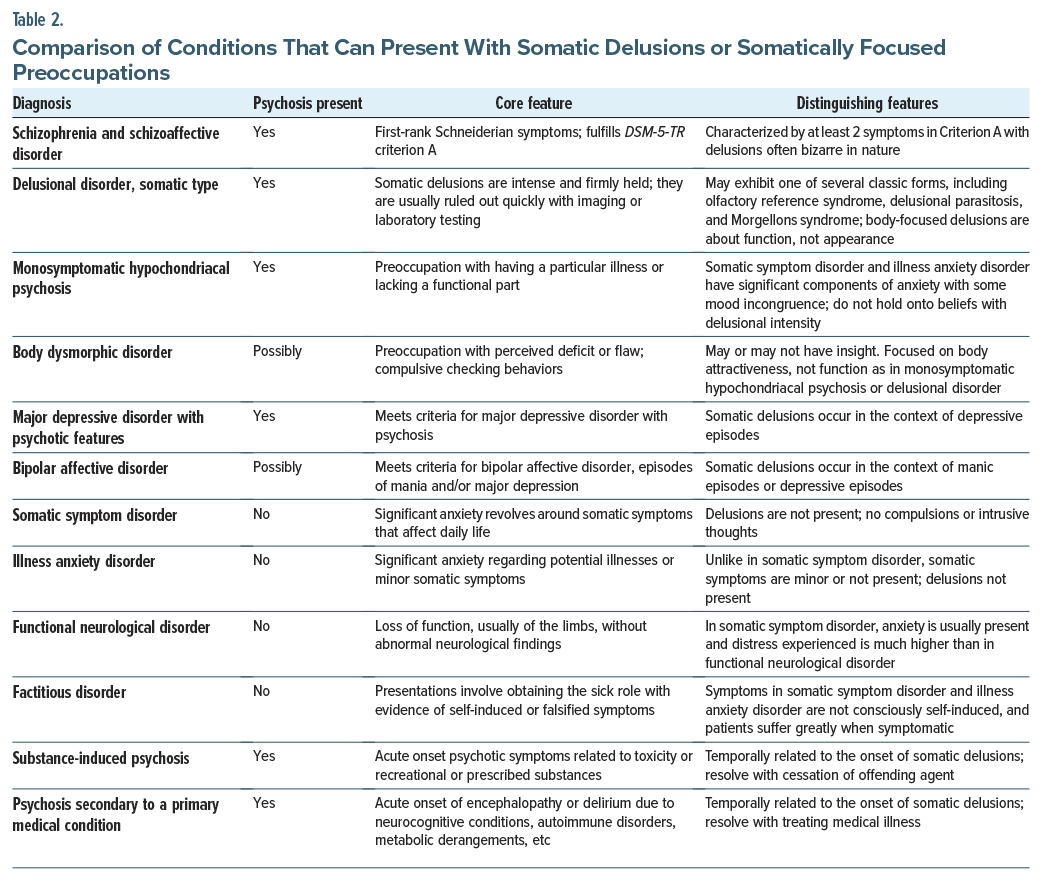

Distinguishing between conditions that involve somatic delusions begins with a thorough clinical history. The onset and nature of the symptoms are critical in guiding differential diagnosis. As somatic delusions are a less common manifestation of primary psychotic illnesses, it is important to generate a thorough differential. Acute onset of symptoms may suggest medication toxicity, recreational substance use, or a primary medical condition. In such cases, symptoms typically resolve after discontinuing the offending substance or treating the underlying medical issue. New somatic delusions may also occur in the setting of decompensation of an existing psychiatric illness (eg, a mood episode in MDD or bipolar affective disorder, psychosis in schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder), so optimization of pharmacologic treatment of known psychiatric conditions is necessary.

Chronic somatic delusions require a more nuanced diagnostic approach, beginning with the consideration of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder (Table 2). If the individual with somatic delusions does not meet Criterion A (2 or more of the following: delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, disorganized behavior, or negative symptoms), the next consideration is delusional disorder, somatic type. Importantly, individuals with a delusional disorder typically maintain relatively intact functioning compared to those with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, with neither their behavior nor the delusion itself appearing bizarre or odd. This high level of functioning can sometimes mask the severity of the condition. Rates of suicidality in individuals with delusional disorder are high, with some studies reporting a prevalence of up to 21%.18 Classical manifestations of delusional disorder include Ekbom syndrome or Morgellons disease, which can aid in diagnosis.

When somatic delusions focus on perceived bodily flaws, BDD with absent insight and monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis should be considered. The key distinction between these illnesses lies in the nature of the preoccupation: BDD revolves around physical appearance or attractiveness, while monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis (ie, delusional disorder) often involves bodily functions or illness concerns. Moreover, BDD is on the obsessive-compulsive spectrum, and this preoccupation is often accompanied by compulsive behaviors. Culturally bound subtypes of BDD also exist, such as shubo-kyofu (fear of having a bodily deformity), koro syndrome (worries that the penis, vulva, or nipples will recede into the body causing death), and jikoshu-kyofu (fear of having an offensive body odor).5(p295)

Several conditions involve somatic symptoms without delusions, but they still warrant consideration in the differential. Somatic symptom disorder is characterized by the presence of multiple distressing somatic symptoms that significantly disrupt daily life. Illness anxiety disorder (IAD), formerly hypochondriasis, is marked by preoccupation with having, or acquiring, a serious illness, despite the absence of significant physical symptoms. Unlike delusional disorder (ie, monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis), the individual with somatic symptom disorder or illness anxiety disorder may not firmly believe their symptoms are indicative of a serious illness, although they may worry excessively about their health and their experience of significant functional impairment. The patient with delusional disorder holds firmly to their belief, even in the setting of evidence to the contrary. Pseudocyesis, the belief of being pregnant that is associated with objective, observable signs and symptoms of pregnancy, is also a somatic symptom disorder. It must be distinguished from delusional pregnancy.4 Functional neurological symptom disorder (formerly conversion disorder) involves physical symptoms (eg, blindness, seizures) that are not explained by any medical condition. These symptoms are often thought to be related to psychological stress or trauma, though the patient may display a marked lack of concern for these symptoms termed la belle indifférence. In factitious disorder, the individual intentionally produces or feigns symptoms to take on the “sick role” for emotional gain. Diagnosis of factitious disorder requires evidence of deliberate deception, which can help differentiate it from other conditions with unintentional symptom presentations.

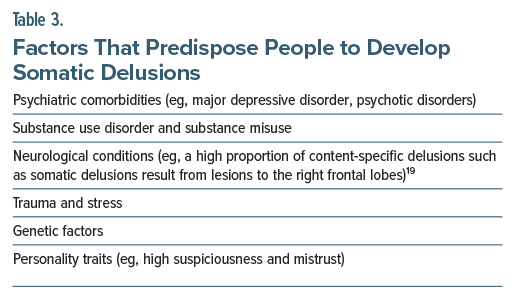

What Factors Predispose People to Develop Somatic Delusions?

Table 3 provides factors that predispose people to develop somatic delusions (including psychiatric and neurological conditions19).

Why Do Individuals With Dementing Illnesses Develop Somatic Delusions?

Patients with dementing illnesses commonly develop delusions of different types, including somatic delusions (ie, fixed beliefs of physical symptoms for which organic causes are not discoverable).20,21 Many theories have been proposed about the etiologies of delusions in patients with dementing illnesses. In general, delusions could be (1) caused directly by underlying brain damage associated with the dementing illness, (2) due to patients attempting to understand their environment, (3) secondary to mood changes, or (4) be a coincidental diagnosis that is concurrent with but unrelated to the dementing illness.22

While limbic dysfunction might play a key role in the formation of delusions, other factors shape the content and complexity of the delusional beliefs.23 In this context, preoccupation with normal bodily sensations and excessive concern over the meaning or source of these sensations or pain may contribute to the content of delusional beliefs becoming somatic.24

How Can Somatic Delusions Be Managed?

Treatment of somatic delusions may involve a multimodal treatment approach that incorporates pharmacotherapy, somatic treatments, and psychotherapy. Antipsychotics are often the first line of pharmacologic management. Pimozide, a first-generation antipsychotic, has shown efficacy in delusional parasitosis, a prototypical somatic delusion, although second-generation antipsychotics (eg, risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole) are now more commonly used due to better tolerability and comparable effectiveness.25–27 The choice of antipsychotic often depends on side effect profiles, patient comorbidities, and individual response. Antidepressants such as clomipramine have also proven efficacy, especially in patients who do not respond to antipsychotics.28

In treatment-resistant cases, somatic interventions (eg, electroconvulsive therapy [ECT] and transcranial magnetic stimulation [TMS]) may be beneficial. ECT has demonstrated efficacy in patients with severe mood disorders with psychotic features, including somatic delusions, particularly when there is a high level of distress or functional impairment.5,29 TMS, while less established, has emerging evidence suggesting utility in modulating cortical regions implicated in somatic delusional processing, such as the temporoparietal junction.30 Additionally, ketamine, primarily known for its rapid-acting antidepressant effects, has shown preliminary evidence in reducing psychotic and somatic symptoms, particularly in depressive disorders.31

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), particularly CBT for psychosis, can play a crucial adjunctive role. CBT targets maladaptive beliefs and cognitive distortions underlying the delusional content, helping patients reframe somatic misinterpretations and improve insight.32 Integrated treatment models that combine medication management with structured psychotherapy are associated with better outcomes and reduced relapse rates in patients with somatic delusions.

How Can You Manage Seemingly Inappropriate Requests for Subspecialty Consultations and Testing From Patients With Somatic Delusions?

Using an approach that emphasizes shared decision-making may be most helpful, rather than employing a paternalistic approach (in which the health care provider tells the patient what is best for them and what they should do). Such an approach can unearth the sources of distrust or paranoia that often impede conversations. One can look at the therapeutic options and offer a statement, eg, “Would you be willing to try this for a while so that we can see whether it is alleviating your distress and then we can review our options and see whether and what type of testing is necessary?” Using “we” and “our” pronouns facilitates the view that you are working together and helping to mitigate symptoms that are bothersome to them.

Moreover, attempts to alleviate their distress about their symptoms (rather than the thoughts and beliefs that are viewed as psychotic by others) frequently resonate with patients. This may allow clinicians to initiate a brief trial of an antipsychotic to reduce distress and help them sleep.

What Happened to Mr A?

Mr A was admitted to an inpatient psychiatry unit for stabilization. A brain magnetic resonance imaging scan and thyroid-stimulating hormone, vitamin B12, vitamin D, complete blood cell count, urinalysis, and metabolic studies were unremarkable. The consensus (among the psychiatrists and neurologists who consulted on him) was that he was not suffering from a neurodegenerative disease. His Montreal Cognitive Assessment33 score was 28/30. He was diagnosed with MDD with psychotic features and started on risperidone (the dose was increased from 1 mg to 3 mg over the course of a week). Risperidone appeared to contribute to hypotension and tachycardia (initially caused by his hypovolemia due to poor oral intake), and it was discontinued. Aripiprazole 5 mg/d was started, and it reduced his delusional thoughts. However, he developed akathisia, which led to a dose reduction to 2 mg/d that eliminated akathisia. After a 2-week inpatient stay, his condition appeared to be resolving. His somatic delusions and fears of imminent bankruptcy disappeared. However, his social anxiety and withdrawn affect persisted.

CONCLUSION

We described the case of a man who developed somatic delusions in the context of multiple acute and chronic medical and psychiatric problems to illustrate the biopsychosocial complexity from which somatic delusions can arise. As demonstrated by our case, many etiologies can play a role in the pathogenesis of psychotic states. We reviewed the broad differential diagnosis of somatic delusions and described treatments that have been shown to improve or resolve delusional states and relieve patient suffering, likely by correction of neurochemical imbalances.

Article Information

Published Online: October 16, 2025. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.25f03990

© 2025 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Submitted: April 24, 2025; accepted July 3, 2025.

To Cite: Rustad JK, DeSimone AC, Goodman ZS, et al. Somatic delusions: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2025;27(5):25f03990.

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Rustad, Goodman, Ho, Schwartz, Li, Felde, Rebhun, Powell); Department of Mental Health and Behavioral Sciences, White River Junction VA Medical Center, White River Junction, Vermont (Rustad, Felde, Rebhun, Powell); Department of Psychiatry, Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont (Rustad); Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (DeSimone); Bayhealth Medical Center, Dover, Delaware (DeSimone); Department of Psychiatry, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (DeSimone); Department of Psychiatry, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire (Goodman, Ho, Schwartz, Li); Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (Stern).

Corresponding Author: James K. Rustad, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, One Medical Center Dr, Lebanon, NH 03756 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: Drs Rustad, Rebhun, Powell, and Felde are employed by the United States Department of Veterans Affairs, but the opinions expressed in this article do not reflect those of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr Stern has received royalties from Elsevier for editing textbooks on psychiatry. Drs DeSimone, Goodman, Schwartz, and Li have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support: None.

Clinical Points

- Somatic delusions are not limited to a single psychiatric diagnosis; rather, they represent a subtype of delusional thinking that can occur across a range of conditions and can manifest in various ways.

- Somatic delusions are observed in schizophrenia spectrum and related disorders, obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, bipolar and related disorders, depressive disorders, substance-induced psychosis, psychosis secondary to medical conditions, and dementia.

- An acute onset of symptoms suggests medication toxicity, recreational substance use, or a primary medical condition; new somatic delusions may also occur in the setting of decompensation of an existing psychiatric illness.

- Chronic somatic delusions require a more nuanced diagnostic approach, beginning with the consideration of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

- Management of somatic delusions involves a multimodal treatment approach incorporating pharmacotherapy, somatic treatments, and psychotherapy.

References (33)

- Cohen JL, Vu MHT, Beg MA, et al. Successful resolution of prominent somatic delusions following bi-temporal electroconvulsive therapy in a patient with treatment-resistant schizoaffective disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2019;49(2):52–56. PubMed

- Crişan C, Androne B, Barbulescu LD, et al. Nexus of delusions and overvalued ideas: a case of comorbid schizophrenia and anorexia in the view of the new ICD-11 classification system. Am J Case Rep. 2022;23:e933759. PubMed

- Paolini E, Moretti P, Compton MT. Delusions in first-episode psychosis: principal component analysis of twelve types of delusions and demographic and clinical correlates of resulting domains. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:5–13. PubMed CrossRef

- Bera SC, Sarkar S. Delusion of pregnancy: a systematic review of 84 cases in the literature. Indian J Psychol Med. 2015;37(2):131–137. PubMed CrossRef

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. In: text rev. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 2022.

- de PE, González N, Haro JM, et al. A descriptive case-register study of delusional disorder. Eur Psychiatry J Assoc Eur Psychiatrists. 2008;23(2):125–133.

- Comardelle N, Edinoff A, Fort J. Delusions of glass under skin: an unusual case of somatic-type delusional disorder treated with olanzapine. Health Psychol Res. 2022;10(3):35500. PubMed CrossRef

- Mindru FM, Radu AF, Bumbu AG, et al. Insights into the medical evaluation of Ekbom syndrome: an overview. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(4):2151. PubMed CrossRef

- Dib El Jalbout J, Sati H, Ghalloub P, et al. Morgellons disease: a narrative review. Neurol Sci. 2024;45(6):2579–2591. PubMed CrossRef

- Ajiboye PO, Yusuf AD. Monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis (somatic delusional disorder): a report of two cases. Afr J Psychiatry (Johannesbg). 2013;16(2):87–89. PubMed CrossRef

- Dols A, Rhebergen D, Eikelenboom P, et al. Hypochondriacal delusion in an elderly woman recovers quickly with electroconvulsive therapy. Clin Pract. 2012;2(1):e11. PubMed CrossRef

- Chernyak Y, Chapleau KM, Tanious SF, et al. Olfactory reference syndrome: a case report and screening tool. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2021;28(2):344–348. PubMed CrossRef

- Dihingia S, Bhuyan D, Bora M, et al. Cotard’s delusion and its relation with different psychiatric diagnoses in a tertiary care hospital. Cureus. 2023;15(5):e39477. PubMed CrossRef

- Slattery H, Nance M. Treatment resistant somatic delusions in bipolar disorder. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2014208375. PubMed CrossRef

- Fiorentini A, Cantù F, Crisanti C, et al. Substance-induced psychoses: an updated literature review. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:694863. PubMed CrossRef

- Niebrzydowska A, Grabowski J. Medication-induced psychotic disorder. A review of selected drugs side effects. Psychiatr Danub. 2022;34(1):11–18. PubMed CrossRef

- Skikic M, Arriola JA. First episode psychosis medical workup: evidence-informed recommendations and introduction to a clinically guided approach. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2020;29(1):15–28. PubMed CrossRef

- González-Rodríguez A, Seeman MV. Two case studies of delusions leading to suicide, a selective review. Psychiatr Q. 2020;91(4):1061–1073. PubMed

- Gurin L, Blum S. Delusions and the right hemisphere: a review of the case for the right hemisphere as a mediator of reality-based belief. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;29(3):225–235. PubMed CrossRef

- Kumfor F, Liang CT, Hazelton JL, et al. Examining the presence and nature of delusions in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia syndromes. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2022;37(3). doi:10.1002/gps.5692. PubMed CrossRef

- Greenberg DB, Braun IM, Cassem NH. Functional somatic symptoms and somatoform disorders. In: Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, et al, eds. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. Mosby;2008:319–330.

- Cummings JL, Victoroff JI. Noncognitive neuropsychiatric syndromes in Alzheimer’s disease. Cogn Behav Neurol. 1990;3(2):140.

- Rao V, Lyketsos CG. Delusions in Alzheimer’s disease: a review. JNP. 1998;10(4):373–382. PubMed CrossRef

- Gan JJ, Lin A, Samimi MS, et al. Somatic symptom disorder in semantic dementia: the role of alexisomia. Psychosomatics. 2016;57(6):598–604. PubMed CrossRef

- Dimopoulos NP, Mitsonis CI, Psarra VV. Delusional disorder, somatic type treated with aripiprazole-mirtazapine combination. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(7):812–814. PubMed CrossRef

- Elmer KB, George RM, Peterson K. Therapeutic update: use of risperidone for the treatment of monosymptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;43(4):683–686. PubMed CrossRef

- Manschreck TC, Khan NL. Recent advances in the treatment of delusional disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(2):114–119. PubMed CrossRef

- Wada T, Kawakatsu S, Nadaoka T, et al. Clomipramine treatment of delusional disorder, somatic type. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(3):181–183. PubMed CrossRef

- Ota M, Mizukami K, Katano T, et al. A case of delusional disorder, somatic type with remarkable improvement of clinical symptoms and single photon emission computed tomograpy findings following modified electroconvulsive therapy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2003;27(5):881–884. PubMed CrossRef

- Oriuwa C, Mollica A, Feinstein A, et al. Neuromodulation for the treatment of functional neurological disorder and somatic symptom disorder: a systematic review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2022;93(3):280–290. PubMed CrossRef

- Le TT, Di Vincenzo JD, Teopiz KM, et al. Ketamine for psychotic depression: an overview of the glutamatergic system and ketamine’s mechanisms associated with antidepressant and psychotomimetic effects. Psychiatry Res. 2021;306:114231. PubMed CrossRef

- Lincoln TM, Peters E. A systematic review and discussion of symptom specific cognitive behavioural approaches to delusions and hallucinations. Schizophr Res. 2019;203:66–79. PubMed CrossRef

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. PubMed CrossRef

Enjoy this premium PDF as part of your membership benefits!